Most medieval European chronicles share a fairly common formula. You’d be forgiven for confusing one with another, forgetting their names, ignoring their details.

Yet the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle sits so far outside the norm of a typical chronicle that it demands close attention. Here is a chronicle so unlike the others that I’d bet it’s capable of capturing the interest of people who wouldn’t dream of spending even an instant looking at a chronicle otherwise. Maybe.

So what makes the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle so intriguing?

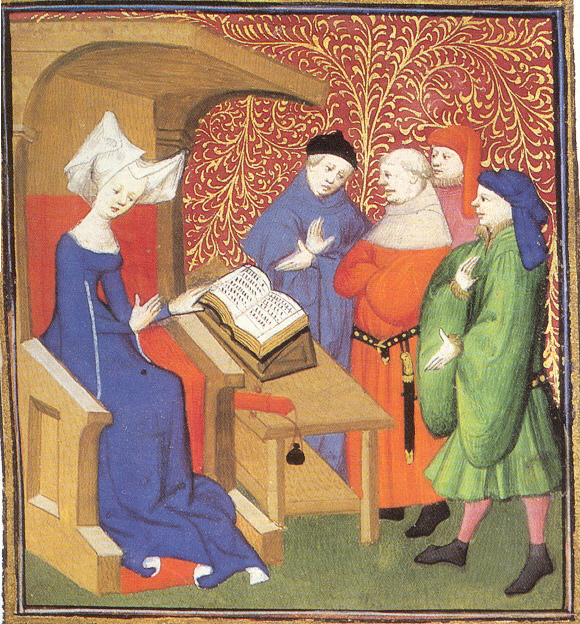

To answer this, let’s consider what makes a typical chronicle typical. What does a ‘normal’ chronicle look like? Firstly, chronicles were traditionally written by monks, or other members of the ecclesiastical class. It was these people that were typically the most literate, and the overwhelming majority of all medieval writing was produced by this group. Because of this, it was common for chronicles to be written in Latin, the official language of the church. Latin unified the written world of central Europe, in a way. One could find chronicles being written in Latin in many of Europe’s corners: Hungary, Wales, the Byzantine Empire, the Iberian Peninsula, Norway.

These chronicles occasionally went back to the very dawn of time, repeating the events with which the world began, as they appear in the Bible. The writer would then track through a ‘standardised’ and ‘accepted’ (and almost totally invented) recount of the days of antiquity, before arriving at the writer’s present day. At this point, the chronicler would record events that occurred in their lifetime, and perhaps also a few generations before. In some cases, one writer would begin a chronicle, recording the events of their own time, before the work was then continued by another individual, who recorded the period after. Some chronicles were more like compilations; collections of a series of writings by different individuals, all recording different periods, strung together in a chronology.

This can often lead to some interesting discordance within chronicles, occasionally with one half outright contradicting the other. For example, the Dieulacres Chronicle, composed in Staffordshire, England, begins as very sympathetic to king Richard II. However, once Richard was captured and deposed in 1399, the writer of the Dieulacres was evidently replaced, and the chronicle from then on strongly and plainly sings the praises of Henry IV, the man who usurped Richard’s throne, sparing no positive words for the former-monarch. At the point in which the chronicle exchanged hands from the first author to the next, a scribe writes:

“In very many places, this [former] commentator condemns the commendable and commends the condemnable: this is a great fault in written records, especially when writing outrageous things about notable people, using hearsay rather than true knowledge, just as they have been written [above] less truthfully and in abundance. This I know for certain because I was present in many places; I saw for myself, and therefore I know the truth.”1

Clearly, some chronicles included a great deal of character and life, featuring the anecdotes and unveiled opinions of their writers. However many others can be characterised by their detached, somewhat impassive approach, an approach that can feel more than a little dull to the modern reader. Few beyond committed researchers and historians would say they find reading a medieval chronicle ‘interesting’. Many are the chronicle pages that read something like: “And the next year X died after long illness. Then Y, son of Z, was expelled by King A, who later granted custody of the castle to B, the former steward of C.”

The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle does not buck the trend across the board, but in the places it does, the results are very interesting. Some features of the Rhymed Chronicle are fairly standard, whereas others are almost unheard of.

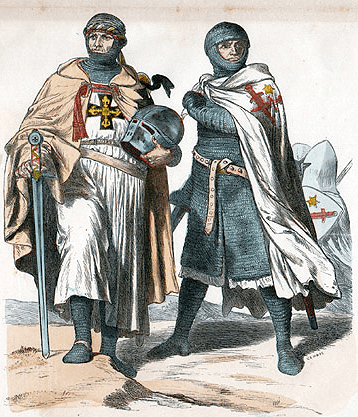

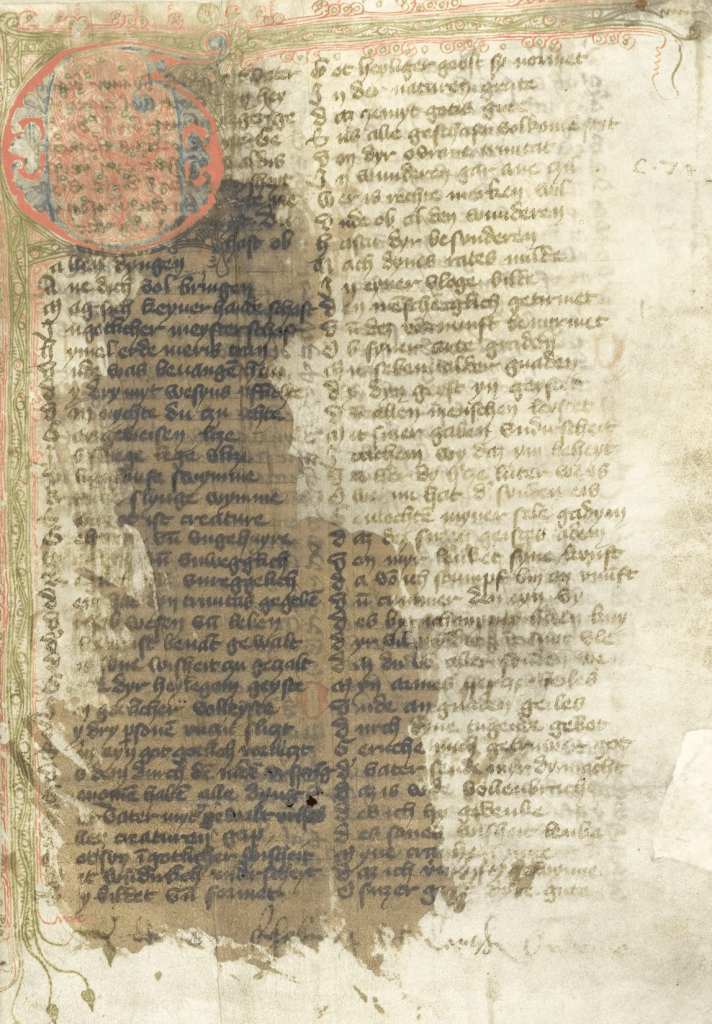

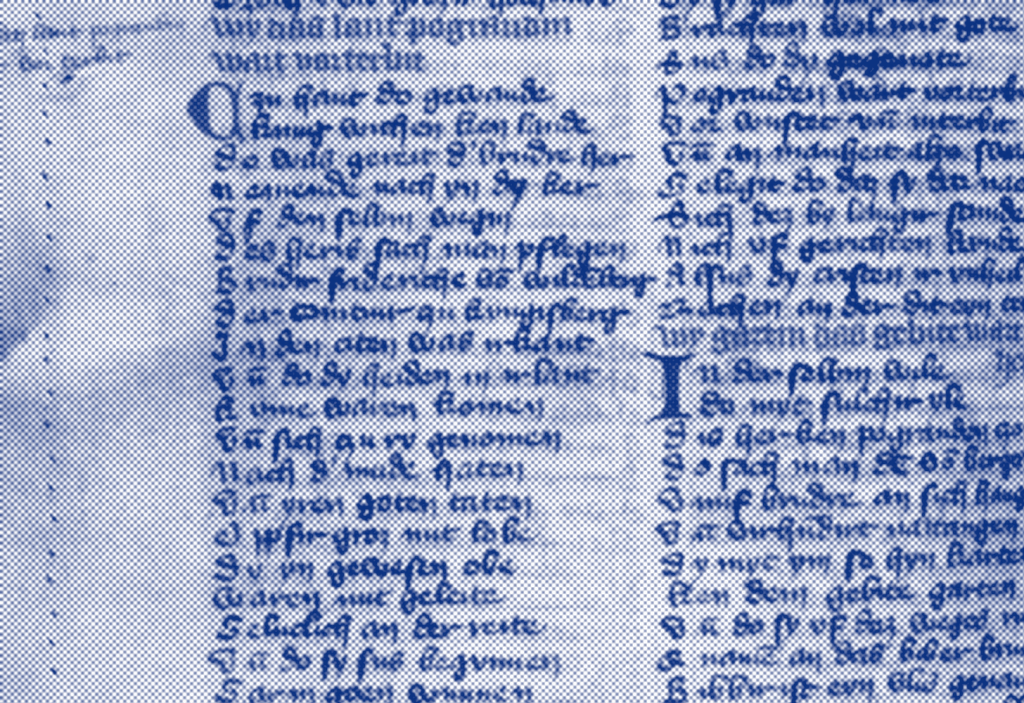

The Rhymed Chronicle is the writing of a single, anonymous author, and spans about a century and a half (1143 to 1290 CE, with a very brief consideration of the creation of heaven and earth at the chronicle’s outset). Whilst the first half of the chronicle was copied from other sources (maybe stories heard by the author), the second half describes events that the writer was personally familiar with, perhaps even witnessing first-hand. Whilst we know very little about this writer, we know he was no monk. Or at least, not a typical monk. Rather than ecclesiastical Latin, the work was composed in Middle High German, which could have been the writer’s own vernacular (more on this later). This work was not composed within a sheltered monastery, but upon the frontlines of the Baltic Crusades. The author was himself a crusader – half-monk, half-soldier – serving the infamous Teutonic Knights. The chronicle records not only the wars of the Teutonic Order, but also the Order of the Sword Brethren, an earlier crusading order active in the area.

Most intriguing of all, however, is the chronicle’s form. As you may have guessed from its title, the chronicle rhymed. This was, for a chronicle recording contemporary events, exceedingly rare. Medieval writers did employ rhyme in ‘mythical’ histories (which were as much fiction as fact) such as Layamon’s Brut, or in heroic narratives such as the Nibelungenlied or Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, but to see rhyme used in what was supposed to be a ‘factual’ account of the author’s present day was exceedingly rare.

The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle was written in what was the standard form for Middle High German epic verse; short rhymed couplets, each line holding three or four stressed syllables.

These are some example lines,

of the aforementioned verse design.

Line one above rhymes with line two,

And of lines three and four, the same is true.

It is thanks to this peculiar relic, the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, the oldest surviving Ordensgeschichte (history of a knightly order), that we can garner a first hand impression of the Livonian Crusade. And this impression we view not through the eyes of a detached and distant chronicler, but through those of one of the men who marched to Europe’s frozen north in order to wage brutal war upon the natives, a war filled with atrocities and horror, all committed in the name of faith.

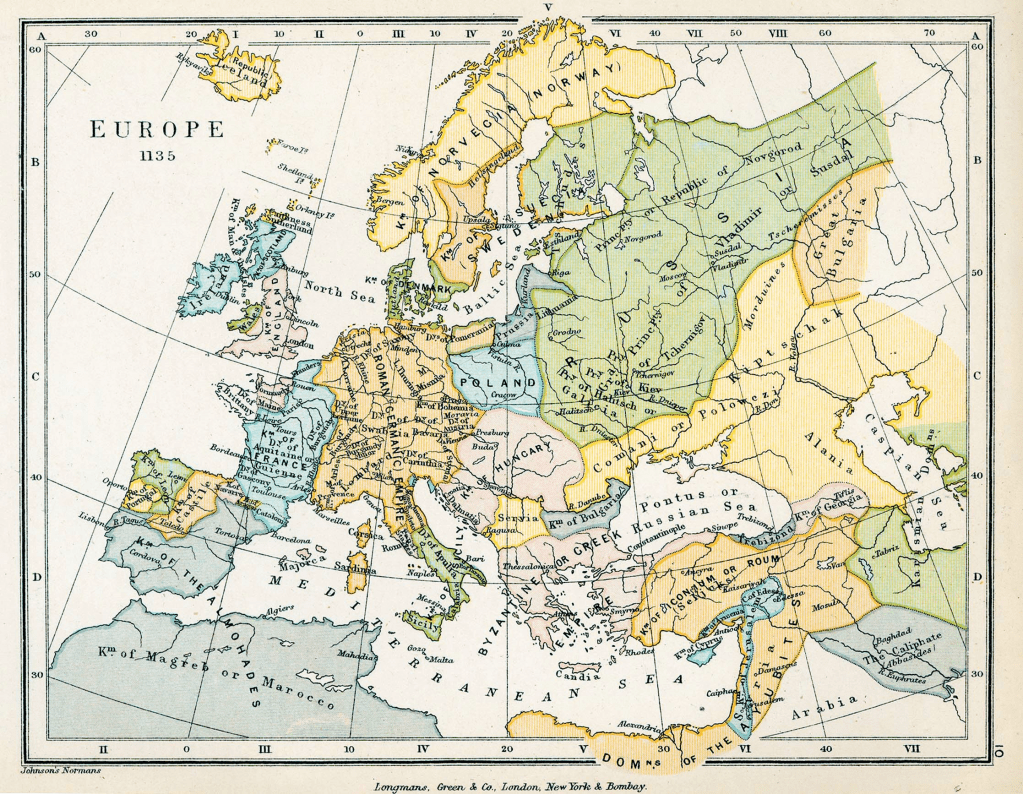

This article is the first instalment of what I hope will be a series on the Baltic Crusades, also known as the Northern Crusades. The Baltic Crusades were a succession of vicious conflicts in which rulers of the Christian states of northern Europe sought to project their influence eastward, into the areas that now compose Lithuania, Estonia, Finland, Poland, Russia and Latvia, trampling the native religions in the process. These conflicts stretch from the 12th century (within which the Livonian Crusade began) all the way into the 15th, ending with the Battle of Grunwald.

The Livonian Crusade started just at the end of the 12th century, beginning in earnest around 1198, but as we shall see, its dawn can be traced back to at least 1143. To gather a better impression of the event, we can start by looking at one of the most extensive surviving sources: the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle.

This article will explore what the Rhymed Chronicle can tell us about the start of the Livonian Crusade, as well as the purpose and intention of the chronicle itself. But first, we will consider why this chronicle is so peculiar – why does the Rhymed Chronicle rhyme?

What was the incident inciting,

this Crusader to rhyme in his writing?

Or; why not just write a non-rhyming chronicle?

Why go through all the extra effort of having the chronicle rhyme, when you could simply write it in prose, saving plenty of trouble and time?

Arguably, this strict adherence to the rhyming structure does degrade the quality of the chronicle in places. Imagine how challenging you might find it if you had to write a history of the company you work for, school you attend, or a club you are a member of. You might have to stretch back in time to record the details of the organisation’s foundation, remembering key figures and describing pivotal events, most likely events you weren’t present to witness, or perhaps events that occurred before you were even alive. Imagine the time and effort it would take to write down this immense record, and now imagine how much harder that task would become if you had to make that written record rhyme. This is the challenge the chronicler imposed upon himself. At times the author was compelled to twist the word order into strange formations in order to create a rhyme or maintain rhythm – much like I had to do in the subheading above…

In other places, the author was forced to repeat lines that serve only as filler to force a rhyme he could not otherwise, such as daz ist wâr (that is true) or daz was wâr (that was true).

In lines 294-296 he writes:

sie brâchten manchen man in nôt

beide stille und offenbâr;

daz ich ûch sage daz ist wârThey brought many men into distress

both silently and openly;

what I tell to you, that is true.

In lines 480-482:

diz feschach von gotes geburt

tûsent un hundirt jâr

und drî und vierzik, daz ist wâr.This happened after God’s birth

one thousand and one hundred years

and three and forty, that is true.

And again in 756-758:

ûf alle valsche rête,

acht er minner dan ein hâr;

waz er gelobte daz was wâr.Of all false advice,

he cared less than a hair;

what he promised, that was true.

These three examples are only the first three I found, in a chronicle of over 12,000 lines.

So if rhyming the chronicle would have not only multiplied the work the writer needed to undertake, and introduced repetitions and disorder that could have been avoided in prose, why bother?

The answer to this question lies in the document’s purpose.

All chronicles had a broadly similar purpose, and that was to record events that the chronicler deemed important, preserving them for future generations. Beyond this, chronicles had countless auxiliary purposes. They could be used to educate, they could be used to spread or consolidate a certain idea or world view, and they could be used to legitimise or strengthen certain authorities or institutions by portraying events in certain lights.

Of course, chroniclers were at liberty to include almost anything within their writing. It was their choice how far they wished to distort, or to stray from, the ‘truth’, and this allowed them to twist a chronicle to their own means, if they wished. It’s important to remember that whilst chronicles were not widely distributed like a print book of today, it was still entirely possible that their contents could still spread through the ecclesiastical class, other literate individuals, and to further groups with whom the aforementioned had contact.

The Rhymed Chronicle shared many of these purposes. Certainly it was kept as a record of the crusaders’ actions, but it also served to elevate, celebrate, and legitimise their cause. To the members of the Teutonic Order, the chronicle served as a source of both inspiration and information on their order. In a sense, it is not unlike a piece of modern military propaganda. But of course, the chronicle didn’t need to rhyme to achieve this purpose.

Instead, it may be thanks to the Rhymed Chronicle‘s intended use that its author decided to have it rhyme.

The form and structure of the chronicle strongly suggests that it was intended to be read aloud to an audience. For example, the chronicle abounds in direct address, especially the pronoun ir, the nominative plural of du (you). English lacks a plural ‘you’, but we can consider ir to mean something like “all of you”, or if you’re from the States: “y’all”.

Take for example lines 4605-4607:

die dâ mit dem bischove wâren komen,

als ir hie vor hâ vernomen,

die kârten mit im von dan.

Those who had come with the bishop,

as you all have heard here before,

they turned away with him from there.

This is a feature we might not expect to see in a written work that was not intended to be read to an audience. Reading the chronicle aloud would have been a very effective way of transmitting the order’s history to its members, especially when we consider that many of the members would have been illiterate. This would have been especially true of the secular crusaders who came to fight alongside the religious orders.

If it was the case that the chronicle was intended to be read to an audience, then its rhyming structure would have had many benefits. It would have made the text more memorable, it would have aided reading, and it would arguably have made the chronicle more entertaining. By rhyming the text, it ceased to be merely a record of the Teutonic Order, and became instead a source of entertainment.

So where and when was this rhyming piece of propaganda being read?

It has previously been suggested that the Rhymed Chronicle was a Tischbuch, a book read aloud during meal times. However, recent research has cast doubt on this assumption. Professor Alan Murray of the University of Leeds has highlighted, in an excellent article on the chronicle’s structure and language, that the Teutonic Order’s own rules stated that members of the order should spend their mealtimes either in silence or listening to Gotes wort (the word of God). Whilst the Rhymed Chronicle did include religious themes, it would not have constituted “the word of God”. It is far more likely that the brothers of the order spent their mealtimes listening to passages from the Bible.

Whatever the occasions and situations in which the chronicle was read, it is clear that, by having it rhyme, the text became more memorable, more entertaining, and perhaps easier to understand. It would have made for an excellent way to ensure the order’s members were aware of their purpose and history, and of strengthening their personal commitment to the order. Yet still, this oral recital might not have been as effective as we may think.

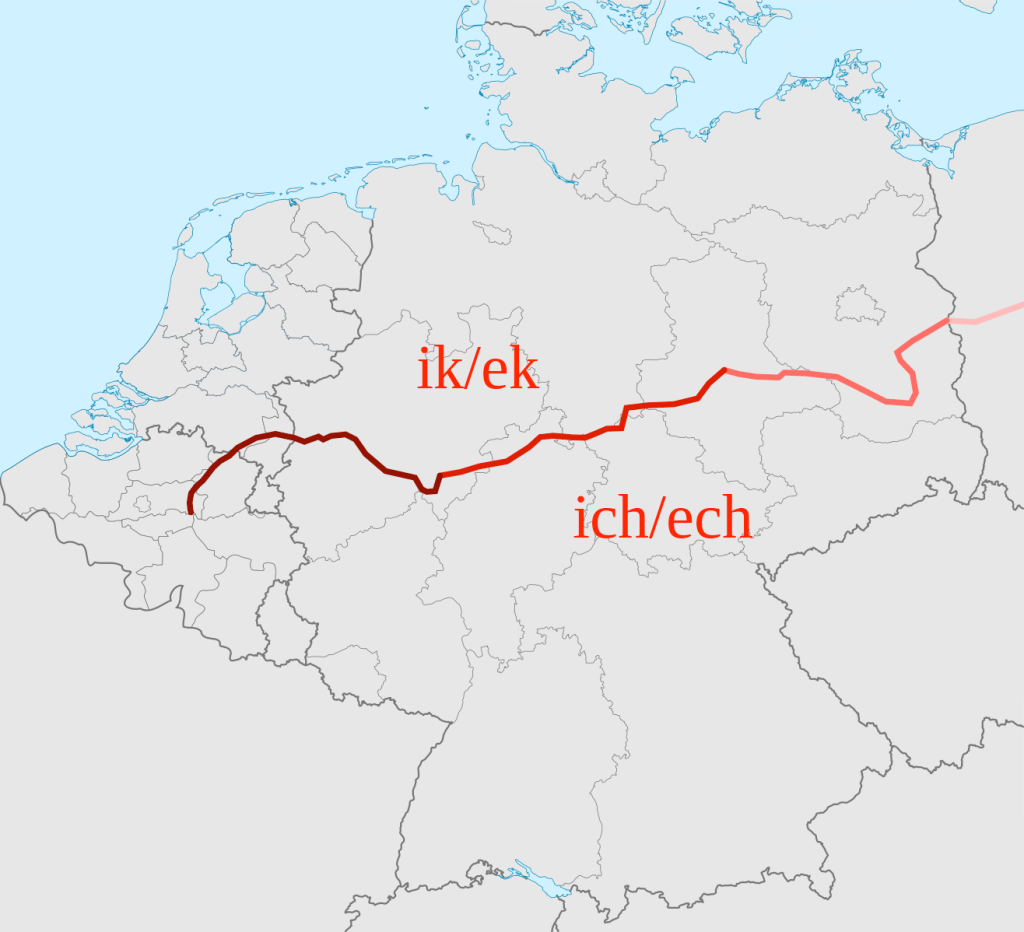

Professor Murray has noted that most of the knights of the Teutonic Order and the Sword Brethren, as well as the secular crusaders who joined them, would have been drawn from northern Germany. These northern folk would have spoken Middle Low German, not the Middle High German of the chronicle. Whilst these dialects would have shared resemblance when written down, they sounded rather different when spoken.

Murray notes that consonants in Middle Low German had not undergone the changes of the Second Sound Shift – a process by which certain sounds in the language changed over time, for instance from /p/ to /ff/ or /p͡f/ – whereas, at this time, the consonants in Middle High German had.

Compare for example:

- hoppe (MLG) and hoffe (MHG) (hope)

- Appel (MLG) and Apfel (MHG) (apple)

- and Schipp (MLG) and Schiff (MHG) (ship).

The effects of this change can still be seen in modern Germanic languages, such as English and Dutch, which retained consonants closer to those found in Middle Low German following the Second Sound Shift: ship and schip in English and Dutch, but Schiff in German.

Speakers of these two dialects would not have necessarily found it easy to understand one another, and these changes, argues Murray, would have caused those listeners of the Rhymed Chronicle who were native Middle Low German speakers to have been “in effect listening to a foreign language”.

This raises the question of why the writer would choose to compose the chronicle in Middle High German if his intended audience would have struggled to understand it. Why not just write it in Low German?

It may be possible that the chronicle’s writer hailed from the south, where Middle High German predominated, thus he wrote in the dialect with which he was familiar. However, there are some hints in the text that High German was not the writer’s native tongue. Murray highlights instances in the chronicle of unshifted consonants such as kop (head) instead of the expected kopf, and blîven instead of High German blîben. Whilst in some cases its possible the author was using an alternative form to force a rhyme, these changes could also be examples of the author slipping back into the habits of his native tongue.

The available evidence can’t conclusively tell us the author’s native dialect, but we can still guess at why he wrote in a dialect unfamiliar to his audience. It is likely that the author was essentially forced to write in High German by the literary standards of the time. Low German had not at this point been established as a dialect suitable for historical writing, whereas High German had been for over a decade.

It is hard to craft a suitable modern-day comparison, but English speakers could imagine it like this: modern legal or medical documents have to be written in a certain ‘legalese’ or ‘medical English’, using a formal style and filled with language that the general public would find impenetrable, even if filling them with casual language and slang would make them more easily understood by wider society. Furthermore, this legal or medical document would probably have to be written in Standard English or General American English, as opposed to a dialect of English such as Scouse or Cockney, even if the people receiving the documents might better understand one of these dialects.

The chronicle’s author was probably constrained by similar cultural expectations of their own time. Murray suggests that this constraint, a requirement to write in the established High German, led to the author needing to avoid subtle meanings and complex language in order to ensure his audience of Low German speakers could still understand the work.

For an in depth examination of the linguistic and structural choices found in the chronicle, I’d highly recommend Professor Murray’s essay.

What does the chronicle tell us?

We have considered the chronicle’s form, but now we should turn our attention to its content. What can the chronicle tell us about the Livonian Crusades, the Sword Brethren, and the Teutonic Knights?

As we attempt to answer this question, we must bear in mind the chronicle’s purpose and audience. The Rhymed Chronicle was written by a Teutonic Knight, for the Teutonic Knights. As mentioned, the chronicle essentially functioned as a piece of wartime propaganda. The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle was to the Teutonic Knights in Livonia what American Sniper was to Americans in Iraq. We cannot expect a balanced record, nor can we expect a remotely sympathetic depiction of those who were the victims of the crusaders’ aggressive expansion into northern Europe.

Recounting all of the events in the chronicle would make this article a mile long, so for today I’m just going to settle with a look at how the chronicle records the start of the crusades, and how it represents the impetus. If you’re interested in reading the entirety of the chronicle in a prose translation, the 1977 Smith and Urban translation is a great option.

The Arrival of Christianity

The chronicle opens with a brief introduction and justification of crusading en masse. From lines 47 to 83 the author writes of how many lands across the world are now filled with Christians where there were formally none, and how the pagan people of these lands threw down the tûvel (devil) and turned to God. Swiftly the author moves on to explain how Christianity came to Livonia, making clear that he learned this second hand. It’s important to remember that the author was writing toward the second half of the crusade, and may not even have been alive during the early days of German activity in the Baltics. Because of this, the chronicle is more than a little confused in some places, and the chronicler occasionally muddles up people, places, and dates. We can tell as much as some of what he says doesn’t line up with other contemporary evidence. What follows below is the history as given by the Rhymed Chronicle.

In the chronicler’s account, merchants had travelled from Germany to the Baltics, arriving at the Dvina river (today known as the Western Dvina or the Daugava). Here the merchants met the Livs and the Selonians, who the writer describes as living in ein heidenschaft vil sûr (a very bitter paganism). They are depicted as a belligerent people, allegedly attacking the Christian merchants as soon as they lay eyes on them. However, we are told the stout defence of the Christians won out, and shortly after, an amiable peace is reached, oaths sworn, and gifts exchanged. Over time the relationship only improves, and the merchants travel further and further inland along the Dvina with each visit. Eventually, the merchants have remained long enough that they decide to construct a settlement, for which the locals have granted them permission. The merchants construct a castle, and they name it Uexküll (Ikšķile). Things seem to be going well.

Meinhard, Berthold, Bloodshed

It is in Uexküll that the peace sours. Here the chronicle introduces us to our first named figure: Meinhard, the priest. He arrives with the merchants, and receives permission from the locals to preach the gospel. However, when the merchants sail home, Meinhard remains. The chronicle tells us that the settlement of Uexküll has begun to trouble the locals; the castle is far mightier than the Livs anticipated when they gave permission for the merchants to build upon the land. Now the pagan Livs start to fear the Christians, whose numbers are increasing daily. As more of the locals convert to Christianity, the Lithuanians, Russians, Estonians, Letts and Öselians (people of the island of Saaremaa, in German Ösel) grow increasingly displeased.

It is then said that Meinhard travels to receive an audience with the pope. Most likely, the chronicle is mistaken here. The historians Smith and Urban suggest it was in fact a man named Theodoric, the principal assistant of the later Bishop Albert, who travelled to meet Pope Innocent III (some time later, in 1203). Regardless, the chronicle claims that it is this event that led to the pope consecrating a bishop in Livonia. Soon after, the situation in Livonia worsens further. It is following Meinhard’s death in 1196 that the crusade begins.

Meinhard’s replacement, Berthold, arrives shortly after the death of his predecessor, and brings with him an army of crusaders intended to subdue the natives who are still resisting the encroaching influence of the Germans. First, the Christians do battle against the Russians and the Lithuanians. The chronicle claims that an entire meadow runs red with blood, and one of the most notable local converts, Caupo, is killed. Later, the Livs send their forces against Berthold. The bishop opposes them with his crusader army, and eleven hundred lives are allegedly lost. Berthold is one of these, dying upon the field of battle. The chronicle claims it is the Estonians that killed him, but this was not the case. Likely the author chose to substitute the Estonians in as Berthold’s foes as they were well known for their prowess in battle, and death at their hands made for a more heroic martyrdom than the truth: that Berthold died fighting the Livs.

Thus began years of bloody war in Livonia. Berthold was replaced by a new bishop, Albert, who brought with him further crusaders. This increasing militarisation of the area is portrayed very simply. The chronicle states the first merchants arrived in 1143, and a preacher (Meinhard) with them. All Meinhard wanted to do, claims the chronicle, is preach. If we take the chronicle at face value, crusaders are being sent to the area to protect the newly Christianised population (and the implanted bishops) from the violent pagans. The chronicle needs to present the history this way in order for it to be effective propaganda.

The chronicle claims the pope then gave his permission for a crusading order to be formed, however, Smith and Urban suggest that the foundation of such an order happened under Theodoric. Regardless, in 1202, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword were born. They would wage war upon the indigenous inhabitants of the area until 1237, when their dwindling numbers were absorbed into the Teutonic Order. This new arm of the Teutonic Knights present in the Baltics would be known as the Livonian Order.

Obscure Intentions, Twisted Pasts

The above introduction is taken from only the first 600 lines of the chronicle’s total 12,017, yet still much is clear from them, despite the ways in which they veil the truth.

To begin with, we are introduced to the supposed purpose of the order. We meet Meinhard, a pious man who only wants to preach to the locals, eager to share the word of God with those in Livonia. Yet in the following years the the situation sours, and by the time Bishop Albert arrives in Livonia, the Germans are engaged in bloody conflict with the Livs, Russians, and Lithuanians. The crusaders are presented as a group sent out to protect the bishops, but these bishops were settlers upon land that was not their own.

It is clear from the outset that this crusade was not a mission of righteous piety, but an exercise of expansion and power projection. The chronicle hides this fact, yet it still reveals part of the truth by accident. From the very start we learn that the Germans came to trade, they came to make money. Soon an outpost was set up on Uexküll and coin was flowing. Ultimately, a crusade could help strengthen this economic expansion through violence mandated by the pope. If the merchants arrived with an army of mercenaries, their intentions would not seem particularly pure. Yet if the bishops arrive with a band of righteous crusaders, their mission is the mission of God. The seal of a crusade gave the invaders the authority to do as they saw fit, as long as they could claim to be spreading the word of God.

The changes and omissions mentioned above only serve to make clearer the chronicle’s role as propaganda. The Livonian Order’s history is ironed out, the awkward creases removed and smoothed over. From their first day they claim to be instituted by the pope, receiving his divine authority from the very start. Smith and Urban point out the mistruth in this, stating in fact that it was Theodoric who founded the Order, and later engaged in a civil war against the then bishop of Riga and the papal legate in an attempt to see which of the three could establish control over the area. The chronicle would seek to have the Order’s members believe that from the start Livonia was filled with pious men united in their march east to spread God’s word, but this was not the case. It was a time of various groups all seeking to establish power over the area, and all using religion as a means to legitimise their presence. Livonia was filled with competing powers, some native, others from the west, and these vied with one another at times and allied together at others. The area was awash with opposing interests, and it was not always clear who would emerge victorious.

Next Time: The Orders of Livonia

Now we are familiar with one of the chief sources on the period, I intend to move on to look at the various groups vying for control. The next instalment of this series of articles will look at the orders who arrived in the Baltics to fight the Livonian Crusade: first the Sword Brothers, and later the branch of the Teutonic Order known as the Livonian Order. What compelled these men to wage their crusade, and against which groups and individuals, native and otherwise, did they fight?

These question we shall consider next time.

Until then, thanks for reading.

Sources

The principal resource I used in researching this article was the introductory background found in the prose translation of The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle edited and translated by Jerry C. Smith and William L. Urban (Bloomington, IN, 1977).

Additional sources utilised are included in the bibliography below.

The extracts of the original poem that I have included throughout the article have been taken from the Livländische Reimchronik edited by Leo Meyer (Paderborn, 1876). These I translated from the Middle High German myself, so any errors are my own.

Anon., Livländische Reimchronik, ed. by Leo Meyer (Paderborn, 1876).

Clarke, Maud C. and Galbraith, Vivian H., ‘The Deposition of Richard II’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 14.1 (1930), pp. 125-181.

Murray, Alan V., ‘The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle as a Transitional Text: Formulaic Language in Middle High German Verse History’, Rilce, 36.4 (2020), pp. 1324-1343.

Smith, Jerry C. and Urban, William L., The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle (Bloomington, IN, 1977).

- Translation of an extract of the Dieulacres Chronicle included in Maude V. Clarke and Vivian H. Galbraith, ‘The Deposition of Richard II’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 14.1 (1930), p. 174.

Any errors in the translation are my own. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Trump’s Israel Policy: How ‘Bad History’ Shapes Politics – Telling Time Cancel reply