In 2008, a financial crisis began in the world’s largest economy — a crisis caused by a speculative asset bubble, predatory lending, excessive leverage, and a lack of regulatory oversight. This crisis rippled across the globe, ultimately causing the most severe economic downturn the world had seen since the Great Depression.

Six years later, in 2014, I failed my economics A-Level, achieving a ‘U’ grade, which in the world of finance stands for unsecured debt instruments, which I have been told contributed pretty heavily to the 2008 financial crisis – but I would need to watch the Big Short again to confirm this. (I give you this second piece of information as a warning to take my thoughts on the economy with a pinch of salt. The information provided is NOT financial advice. I am NOT a financial adviser, etc.)

With that legally-binding disclaimer out the way, what’s the relevance of speculative asset bubbles, predatory lending, excessive leverage, and a lack of regulatory oversight? That was 2008, this is now, so surely we’ve learnt our lesson.

What Could Be Worse Than a Giant Paint Bubble?

It’s now generally understood that the 2008 financial crisis was precipitated (among other things) by a bubble of speculative investments in housing (if you’ve also seen the Big Short, you can skip this paragraph). Regular Americans had become convinced that the rapid rise in house prices was going to keep growing ad infinitum, and many were buying houses not solely to live in, but as investments. As the banks doled out increasingly dangerous loans, bundled mortgages into securities, and received AAA credit ratings for these incredibly risk-laden financial products, the Regular American Investor was vindicated: prices did keep rising. Until, of course, supply increased and demand weakened, interest rates rose, and investors, watching prices flatten, began pulling out. With less buyers, sellers started lowering house prices – and as the Regular American Investor watched the value of a house start to dip, they rushed to sell before it was too late, and housing prices plummeted.

But what is the speculative investment bubble of today? The housing market – at least in the States – is fairly stable. But that doesn’t mean we’ve learnt our lesson about speculative investment.

Enjoying this article so far? Subscribe to get the next one in your inbox.

Speculative investment didn’t start with 2008. One of the most famous cases of a speculative asset bubble takes us back to the 1600s. This period, now known as ‘tulip mania’, occurred shortly after the tulip arrived in the Netherlands. Dutch traders became completely obsessed by rare bulbs of the flower, and a speculative market emerged in which investors were paying exorbitant amounts for tulip bulbs in the expectation that their price would continue to rise. One report claims that a single bulb of a particularly sought-after tulip variety named ‘the viceroy’ was traded for no less than four oxen, eight pigs, twelve sheep, four tuns of beer, two tuns of butter, one thousand pounds of cheese, a bed, a suit of clothes, and a silver drinking cup1. The bubble collapsed suddenly in February of 1637, the price of the bulbs plummeting to near zero in only three months, presumably after everyone realised how absurd it was to drop a labourer’s yearly wage on a tulip bulb.

The Viceroy Tulip – Wageningen University Collection

Much has already been made on the similarities between the tulips of tulip mania in 1637 and the NFTs of NFT mania in 2022, but I don’t feel that’s a fair comparison. Tulips, at least, are nice to look at, and you can’t eat an NFT during a famine.

But just because the vast majority of us have figured out that NFT stands for New Fraud Technique, doesn’t necessarily mean we’re not currently in another bubble of speculation. It’s harder to say if speculation is “reasoned” or not when we start to discuss digital assets and cryptocurrencies. The tulip bubble and the 2008 housing bubble grew when the prices charged and paid for these assets began to separate wildly from their actual value – but whilst we might be able to agree on the intrinsic value of a tulip or a house, can we do the same for a bitcoin? What is the actual value of an asset which is, at its core, no more than a network-validated claim to a value recorded on a blockchain? It could be argued, indeed it is being argued, that the bitcoin bubble is soon to burst, and its value take a tumble.

But it isn’t just digital assets that may be overvalued – traditional investments might also be swollen with speculation. People far better informed than me on the economy have noted that the US stock market currently looks a lot like it’s in a bubble soon to burst, and that we are highly likely to see a “cataclysmic decline in the not-too-distant future,” which sounds reassuring.

Nothing serves as a better example of speculative overvaluation in the stock market like the valuation of Tesla, which despite taking a recent tumble since its CEO developed a stiffness in the elbow, is still, somehow, considered among the “Magnificent Seven” tech stocks – alongside companies like Microsoft, Apple and Nvidia, who make the technology we rely on every single day of our lives, and world-leading surveillance companies like Meta and Alphabet. Meanwhile, Tesla continues to offer a range of six over-priced cars that either fall apart or shed their value the second you drive them out the lot, alongside, of course, repeat promises of a robot perpetually one year away, that will do all the awful, menial work in your life that you hate doing, like walking your dog and spending time with your children.

I’m not necessarily saying that the US crypto or stock markets are in bubbles, but the evidence is compelling. Regardless, what is obvious, is that they’re currently unbelievably volatile. An economically illiterate White House and an increasingly deregulated social media landscape have created a perfect storm, one in which a random Twitter account can knock 4 trillion dollars off the stock market by leaking news of the 90-day tariff pause a week early.

There’s plenty more to be said about market volatility and speculative bubbles – but this article is supposed to be about the Giant Looming Credit Event, so let’s get back to that.

Eat Now, Pay Later

We’ve established that a speculative asset bubble played a part in the 2008 crisis, but this bubble would never have grown to the size it did if it wasn’t for predatory lending, excessive leverage2, and a severe lack of regulation. And whilst you could argue that bitcoin and the stock market aren’t examples of speculative asset bubbles, there’s no way you could argue that we aren’t right now witnessing one of the wildest periods of predatory lending – ever.

Enter Klarna Burrito.

Buy Now Pay Later has become a ubiquitous part of shopping online in the last decade, with the global BNPL market doubling in value over the last three years. Whilst instalment financing on products is nothing new, BNPL today is uniquely troubling due to the small size and large amount of loans being offered, often with little to no oversight, and often without a credit check. From the start, BNPL has been predatory. Targeted to a younger audience and offering an “easy” way to pay for online shopping by splitting payments into smaller, interest-free instalments, it’s perhaps easy to see why half of all Americans admit to having used BNPL at some point. What many users don’t realise is that BNPL providers are essentially just offering loans by another name. Granted, they’re rather attractive looking interest-free loans, but if a user misses a payment and gets slapped with a late fee, their debt can quickly accrue, and this debt, unlike the original loan, might be subject to interest.

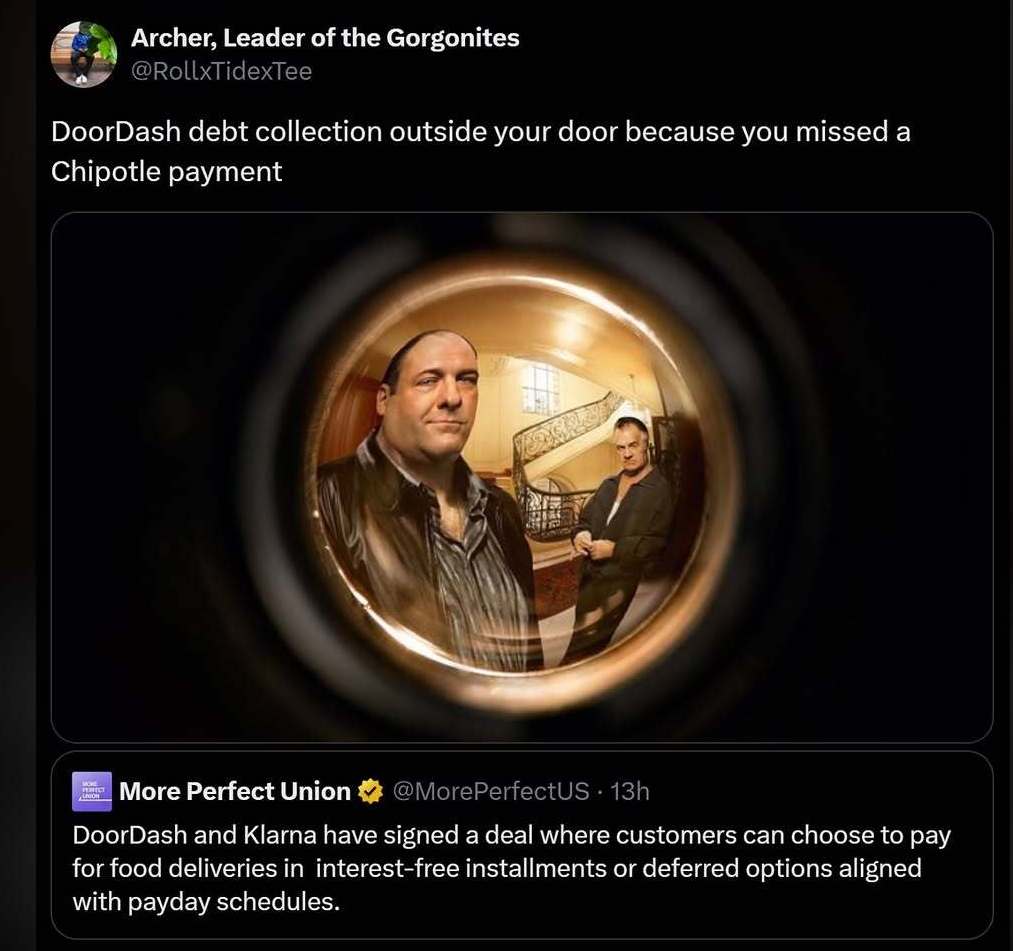

This situation was worrying enough before BNPL heavyweight Klarna announced a partnership with DoorDash in the US and a global partnership with Uber Eats, allowing users to pay for their takeaways on tick.

It’s hard to say exactly why someone might be willing to essentially take out a loan – to go in to debt – for a burger delivered to their door. It could be argued that a society desensitised to gambling and a young generation with an, at best, gloomy outlook on the future are collectively saying “fuck it, why not?” when it comes to debt, charging short-term decisions to life’s credit card to deal with them eventually rather than now – but it goes deeper than cavalier attitudes. I think it’s fair to say that not only have people simply become desensitised to the dangers of BNPL thanks to the overwhelming prevalence of services like Klarna, on top of that, we’re deep in a period of financial misinformation and disinformation, and most users of BNPL simply aren’t aware of the risks.

And how can we expect financial literacy when financial education is so poor? Over 50% of Gen Z and Millennials seek out financial advice on social media, with 52% of those Gen Z respondents stating that they turn to TikTok for financial advice. 52%. TikTok. If you’re turning to TikTok for financial advice, you are, as Gen Z would say, cooked. TikTok, as a platform, does not nurture trust – it does not reward good advice. Unlike platforms like YouTube, in which the algorithm is geared towards repeat access of favoured channels, encouraging creators to give advice that will bring in subscribers and repeat viewers, TikTok’s algorithm rewards virality, encouraging creators to say whatever will generate the most engagement in a 30 second window before a user scrolls past. The same can be said for Instagram Reels. The financial advice on TikTok is about as useful as consulting a Magic 8 Ball or a fortune cookie, maybe even less.

Don’t read this as paternalistic Gen Z bashing either. Some Zoomers (like myself) are old enough to remember the opening of the Millennium Dome, 9/11, and the release of the first Xbox, and even some of the youngest in the Gen Z bracket are capable of making sound financial decisions (age does not necessitate wisdom). The root of the problem is that Gen Z, especially the younger cut of the cohort, are becoming adults within a pretty bleak economic landscape, and they’re not only being preyed upon by exploitative lending from BNPL schemes, but when they turn to their favoured social medium for financial advice, they’re also being preyed upon there.

Lenders like Klarna would like to have you think they’re extending a generous helping hand to the much-maligned youth of the internet-generation, but they’re not – they’re banking instead on their misfortunes. Whilst Klarna claim they’re a favourable alternative to the debt-trap of credit cards, the reality is that they offer a less-transparent and less-regulated product, and are targeting it to a generation being pushed to purchase mountains of cheap crap whilst being drip-fed a diet of financial un-advice on the side.

The willingness of BNPL lenders like Klarna and Afterpay to extend their services to seemingly anyone that wants them might sound like a win for accessibility, an “evening of the playing field” that’s allowing individuals easier access to needed products, but the reality is much darker. In the long run, the fact that Klarna has no minimum credit score requirement to use its services means that individuals already deeply in debt can continue to buy now and pay later with few to no guard rails.

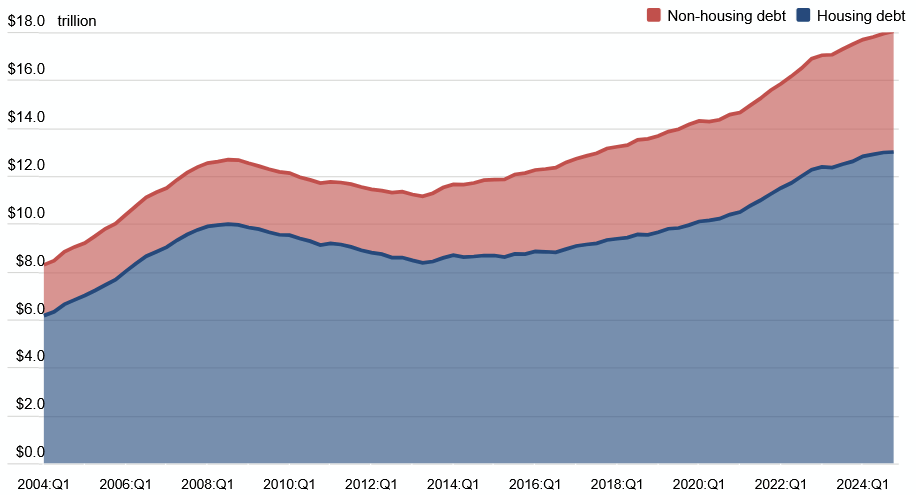

Whilst credit scores are obviously a needlessly obfuscated and byzantine puzzle desperately in need of improved transparency and reform, their core purpose still ultimately protects consumers – credit scores prevent individuals with dangerous borrowing practices from accruing more debt and taking on more credit that they can’t pay off. By setting lax score requirements, BNPLs aren’t helping people with poor credit, they’re entrapping them. This level of unrestrained borrowing is particularly concerning when considered against the rising rates of household debt and credit card delinquency in the US.

Rising debt isn’t necessarily dangerous, but the details of the New York FRB’s Household Debt and Credit Report aren’t reassuring. Whilst they note a modest rise in mortgage debt (which is to be expected in a period of high housing prices), they also note an increase in HELOCs (Home Equity Lines Of Credit). A HELOC allows an individual to borrow against their home, that is, converting part of their home ownership into a loan – in essence, selling back a portion of their home they’ve already paid off to the bank, in exchange for credit. HELOCs are often recommended as a last resort, and an increase in their occurrence indicates that individuals are struggling to cover other expenses – a potential sign of financial stress. Even more concerning is the FRB’s observation on credit card debt: a 45 billion dollar jump in a single financial quarter, a worrying sign of increasing reliance on credit.

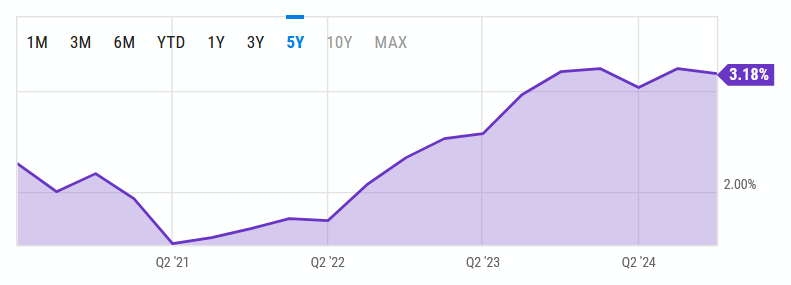

This reliance on credit and increase in borrowing isn’t helped by the high delinquency rate: the percentage of credit card balances that have not been paid on time.

Whilst the debt outlook in the EU is brighter, it’s still plain that any kind of collapse or even instability in the US could have a detrimental knock-on effect.

This increase in debt and defaulting upon it is the backdrop against which we have to judge the ascent of By Now Pay Later. As these rates rise and more individuals accrue new debt, open lines of credit on their homes, and struggle to pay off what they’ve already borrowed, what’s to happen when sections of the population then begin to miss their BNPL payments? This is a reality not too far off. In Germany, one in every three BNPL users have already missed a payment deadline, and that proportion seems set to rise.

So, to recap, we’re now witnessing a rapid influx of predatory lending and credit being extended to a generation raised on increasingly poor online financial advice. And now, with all this credit extended and cash lent, we’re watching default rates rise as more and more people miss payments and slide into debt – and as BNPL expands its reach, its no longer just Boomers and Millennials missing payments on houses and cars and phones like the good old days – its Zoomers failing to pay off burgers, jeans, and toilet paper.

The Small Long

But what does this mean for the economy at large? Sure, it’d be bad for personal finances, and we’re likely to see individuals severely hamstrung by debt – but could this really lead to a Giant Looming Credit Event?

Rising late and missed payments alone are bad for traditional banks – if individuals can’t pay off their loans, then the banks could face liquidity problems and become unable to meet short-term obligations (like customer withdrawals). If trust in banks as a whole is affected, and individuals begin to withdraw savings en masse, this could trigger a broader financial panic like that seen in 2008, raising the risk of bank failure. We’re not immune to such panics in the current day either: mass, fear-driven withdrawals led to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023.

But what’s this got to do with BNPLs? Well, failure by customers to repay what they own to BNPLs can cause similar issues to those in traditional banks, with BNPLs also hit by liquidity strain – stuck having dished out the money, with none coming back in.

Here’s the kicker though. How are BNPLs like Klarna making money? Sure, some of it is just sniping consumers with late fees, but a bigger part of it is what they’re doing with customer debt.

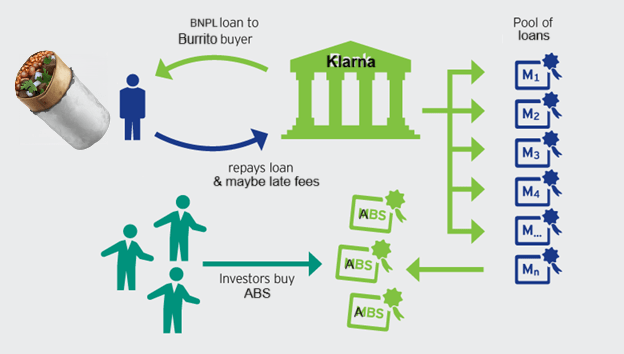

Remember 2008 (or the Big Short)? When the big banks handed out mortgages to customers, they bundled these into mortgage-backed securities and sold those on to investors (good for the bank, because they get the full value of the loan back immediately). These investors – which included other banks, hedge funds, and pension funds around the world – then got paid as homeowners made their monthly payments (good for investors, because they swap an upfront lump-sum for a steady cash flow). But when homeowners defaulted on their mortgage payments – these investments collapsed in value. Result: 2008.

BNPLs like Klarna, Affirm, Afterpay, and PayPal are all doing almost the exact same thing, right now. These companies are bundling customer debt into asset-backed securities and selling them on to investors around the world, just like the big banks did with mortgage-backed securities in ’08. If default rates on BNPLs rise, and customers stop being able to clear their debts, then the investors (which again, include banks and pension funds) are left holding assets which aren’t paying out. I’m not going to shed any tears for the hedge funds – but the effects of pension plans drying up need no explanation.

The bottom line is that whilst BNPLs might not pose the same scale of risk as the mortgages of pre-2008, they still represent a rapidly expanding layer of consumer debt becoming increasingly integrated into global financial markets. If the debt bubble continues to grow, when friction turns to fractures, the results could be wide-reaching. Our parents got a financial crisis made from missed payments on mortgages, we might get one because we can’t pay off the interest on a burger.

But wait! We’ve talked about asset bubbles and predatory lending – but wasn’t a lack of regulatory oversight also crucial in precipitating the 2008 crisis? Isn’t that a relevant factor now?

No, obviously that’s not relevant now. Do you mean to tell me that the world’s largest economy is currently struggling under an absence of intelligent financial leadership and a lack of regulatory oversight? Don’t be silly.

I’m sure they’ve got this under control.

Thank you very much for reading.

I’d like to take this chance to remind you that I’m not really qualified to talk about finance (but hey, that’s stopping neither TikTok gurus nor politicians, is it?) – so please don’t take any of these reflections as gospel. Don’t start withdrawing your savings and hiding them under the bed. At least wait until I take mine out first.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to receive emails when I share future writing. I’m hoping to put up a paywall soon so I can stop paying for my groceries in instalments.

Thanks again.

- This trade, reported in an 1852 examination of tulip mania, has since been disputed, but other, better established, transactions are still mind-boggling – such as a record of one bulb going for 224 guilders at the height of the mania. 224 guilders would have had the value of around 2.3 kilos of silver at the time. ↩︎

- Excessive leverage: people and companies taking on high debt in relation to their income or assets – if the individual or company’s income dips or interest rates rise, they’re likely struggle to with their debt payments. In 2008 excessive leverage was overlooked as the market was convinced that house prices would go up forever and homeowners believed that if they were ever struggling with repayments they could just sell or refinance their property later.

I thought I’d give a clear explanation of excessive leverage here and now as I don’t discuss it any further in the article (because, let’s be honest, it’s pretty boring). ↩︎

Leave a comment