On January 24th 2024, Pete Hegseth was confirmed as the US defence secretary, after securing senate confirmation by the margin of a single vote. Hegseth, Trump’s nomination to sit at the helm of the world’s most expensive military, is also the author of the 2020 book “American Crusade”. In it, Hegseth writes:

“Enjoy Western civilization? Freedom? Equal justice under the law? Thank a crusader.”

But why? Presuming Hegseth is referring to the Crusades In the Holy land, why should his readers attribute Western civilisation, freedom, and equal justice, to the bands of Europeans who marched to Jerusalem almost a millennium ago?

As the adage goes; to understand the future, one must understand the past. So if one misunderstands the past, what will become of the future?

If the US secretary of defence holds such a warped view of the medieval conflicts that shook the Holy Land, how might this affect his perspective on today’s conflict in the same region?

Given Hegseth is a self-proclaimed Christian Zionist who fundamentally opposes a two-state solution, one must wonder how his (mis)understanding of the Crusades relates to his political stance.

Hegseth is just one of Trump’s recent nominees who appear to have their stance on Israel dictated by flawed understandings of history.

In his campaign and since his election, Trump has sought to present himself as a peacemaker, promising to bring about an end to both the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. Only time will tell if he can achieve these aims, and if so, what cost his achievement will come at, and for whom this cost will be greatest.

We will use as proxies three of Trump’s nominees for cabinet and staff positions relating to Israel and the Israel-Palestine conflict, in order to illustrate the new administration’s stance.

The three nominees that shall be considered are: Elise Stefanik for UN ambassador, Mike Huckabee for envoy to Israel, and Pete Hegseth for defence secretary.

Note: At the time of writing, Stefanik and Huckabee are both awaiting senate confirmation.

Whilst Hegseth’s views seem to be chiefly influenced by his understanding of medieval history, Huckabee and Stefanik appear to have their stances guided by their conceptions of ancient history. As ancient history comes first, that’s where we’ll start.

“Biblical Right”

During her senate confirmation hearing that began on January 21st, Stefanik claimed that Israel has a “biblical right” to dominion over the occupied West Bank.

Huckabee has taken an even more extreme line, stating in 2017 that “there is no such thing as a West Bank. It’s Judea and Samaria,” and in 2016, during his failed presidential campaign, that “there’s really no such thing as a Palestinian.”

What could they possibly mean?

How can the Bible be used to justify a claim to land? How can it be possible that there’s “no such thing as a Palestinian” if there are an estimated 15 million Palestinians in the world?

These statements reflect a religious fundamentalism entwined with the interpretation of the Bible as a historical document. A politician claiming that the Bible bestows upon a certain group a right to specific land can be viewed as nothing else than an immense and inextricable interlacing of church and state.

Stefanik’s claim of biblical right rests upon the verses of Genesis 15:18 and Joshua 1:4, both of which detail God’s promises to Abraham and Joshua respectively, of all the land between the Mediterranean and the Euphrates – land encompassing the modern nations of Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. Alternatively, Stefanik’s argument could be based upon Numbers 34, in which God promises Moses an area that more closely corresponds with the land claimed by the World Zionist Organisation at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. It should be noted that, at the time of the Peace Conference, 90% of this land was occupied by Palestinians, who unanimously opposed the Zionist project.

Huckabee and Stefanik’s statements are also symptomatic of an ignorance of more recent history: of the Paris Peace Conference, of the Balfour Declaration, of British Mandatory Palestine.

I am not here to debate, unpick, or debunk anyone’s religious beliefs. I believe all should be entitled to practise their faith as they see fit, providing this practice does not harm others. That said, the views expressed by Stefanik rest upon a belief that what the Bible records is not only incontrovertible fact, but that it is fact which should guide international policy.

Huckabee’s claim that there is “no such thing as a West Bank” and that the area is “Judea and Samaria” is presumably based upon the understanding that the names ‘Judea’ and ‘Samaria’ predate the name ‘West Bank’. And it’s true that they do; the Kingdom of Judah is attested in the archaeological record as early as the 9th century BCE, whereas it was only in 1948 that the name West Bank entered use. Yet Huckabee is intimating that any place known by anything other than its earliest name cannot exist.

That a politician of the United States of America would make such a claim is ludicrous.

Would we expect Mike Huckabee to say that “there is no Washington DC. It’s Anaquashatanik, it’s Kittamaqundi, it’s Patuxent”?

Can it truly be said that a place does not exist merely because it was known by a different name three thousand years ago? How many modern states would be condemned to non-existence if we applied this rule across the world?

If Mike Huckabee is earnestly advocating for returning all peoples across the globe to the lands their distant ancestors inhabited during the Bronze Age, perhaps the US should lead the way, and start by giving their land back to the Native Americans?

Huckabee’s statements oversimplify an incredibly complex and often tragic history. The groups that ejected the Jewish people from Judea and Samaria were first the Assyrians in the 8th Century BCE, the Babylonians in the 6th Century BCE, the Romans in the 1st Century CE, then the Christians of the Byzantine Empire in the 4th Century. It was not until the 7th Century, with the conquest of the Rashidun Caliphate, that any sizeable Muslim population existed in the region. To present the area’s history as a black and white struggle between Jews and Muslims since time immemorial is a gross misrepresentation.

Given Huckabee’s previous cavalier treatment of the Holocaust, I think it is reasonable to argue that he is evidently utilising the historical oppression and displacement of Jewish people as a means to support his political aims, and is misrepresenting Jewish history in order to fit it within his own Christian beliefs.

To close the book on Huckabee and Stefanik, it is clear that dictating foreign policy on the basis of a religious text is not merely unwise, but potentially very dangerous. Their statements rest upon narrow, cherry-picked and mischaracterised shreds of ancient history, overlooking the peaceful coexistence of Jews, Christians and Muslims in Palestine prior to 1919. Both Huckabee and Stefanik dress the current conflict as one that has raged for millennia, and one that is at its core about religion and not about land, settlement, and colonisation.

Their statements fuel a conception of the world in which Christianity and Judaism are locked in a battle of ideologies against Islam. Another individual who tirelessly peddles this world view is Pete Hegseth.

The American Crusade

Whilst it could be argued that Huckabee and Stefanik’s views are more guided by religion than history, Hegseth (whilst evidently also guided by both) has had his stance shaped by a far greater and more blatant failure to grasp historical fact, specifically that of the Crusades.

Despite the fact that Hegseth has written a book on the Crusades, and invokes them often, he has absolutely failed to understand them.

Or worse, he does understand them, and he is wilfully misrepresenting them. As I have stated before in my analysis of right-wing characterisations of the Anglo-Saxons, it is not always easy to separate misrepresentations from misunderstandings.

To begin, what were the Crusades?

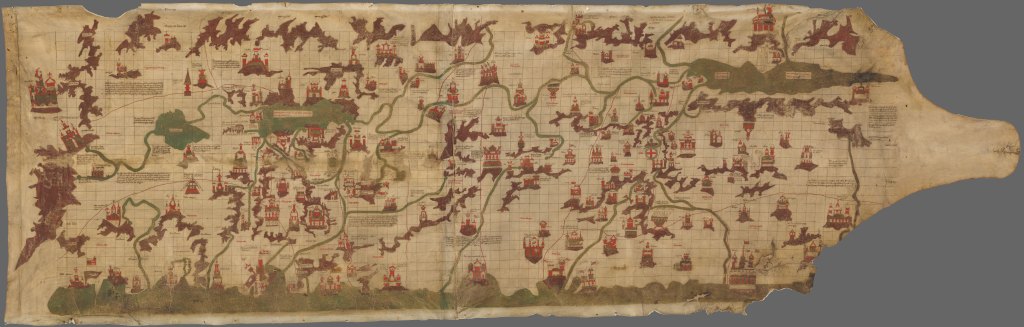

The Crusades refer to a series of religious conquests initiated by the medieval Christian church, that sometimes (but not always) set their sights on the Holy Land with the stated objective of reconquering Jerusalem.

I would presume, that when Hegseth talks of the Crusades, he is talking of these expeditions to the Holy Land, rather than the Cathar Crusades in France, the Livonian Crusades in the Baltics, or the Lithuanian Crusades in Lithuania and Poland.

The Crusades to the Holy Land began with the First Crusade in 1095, and their end point is typically given as the Fall of Acre in 1291.

So, what did the Christians achieve in this almost three hundred year span that makes Hegseth so proud? What did they do to deserve our gratitude today? Why does Hegseth think the Crusaders were there in the first place?

Let’s take a look at some excerpts from Hegseth’s book in order to interrogate these questions, and identify how he’s pushing the wrong answers.

Hegseth writes:

“By the eleventh century, Christianity in the Mediterranean region, including the holy sites in Jerusalem, was so besieged by Islam that Christians had a stark choice: to wage defensive war or continue to allow Islam’s expansion and face existential war at home in Europe.”

And he is wrong.

There was no danger of any existential war in Europe. It is true that the already collapsing Christian Byzantine Empire did face the advances of the Seljuk Turks on its Eastern borders, but there is no evidence to suggest that Europe was in danger. The chief motivation was Christian control of Jerusalem, not the prevention of an existential invasion to Europe.

It is true that southern Spain was at the time under the control of the Muslim Caliphate of Córdoba, but this state was disintegrating rapidly in the 11th Century, and posed no threat to Europe. It evidently didn’t worry the leaders of Europe: the fighters of the First Crusade weren’t heading for Spain.

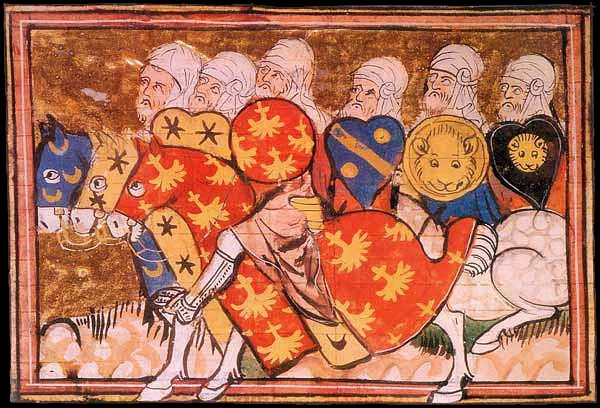

Instead, they marched to Jerusalem, led by an untrained army of peasants who had been gripped by the religious fervour whipped up by Pope Urban II and a priest named Peter the Hermit. This Crusade, known as the People’s Crusade, had the stated aim of travelling to the Holy Land in order to defend the Byzantine Empire and retake Jerusalem. Yet this peasant army hadn’t even left Europe before it started spilling blood. These men marched through France and Germany, massacring the Jewish community on their way. It’s estimated that the Crusaders killed between 2,000 and 12,000 Jews as they travelled through Europe. The vast majority of these Crusaders never even made it to the Holy Land. Those that did arrive behaved so abhorrently within the Christian city of Constantinople that the Byzantine Emperor, who invited them in the first place, turned them away.1 Are these the people Hegseth wants us to thank for freedom?

He adds:

“The leftists of today would have argued for ‘diplomacy’ … We know how that would have turned out.”

This line demonstrates nicely how Hegseth is more concerned with perpetuating his political beliefs and wading into the culture war rather than earnestly representing history.

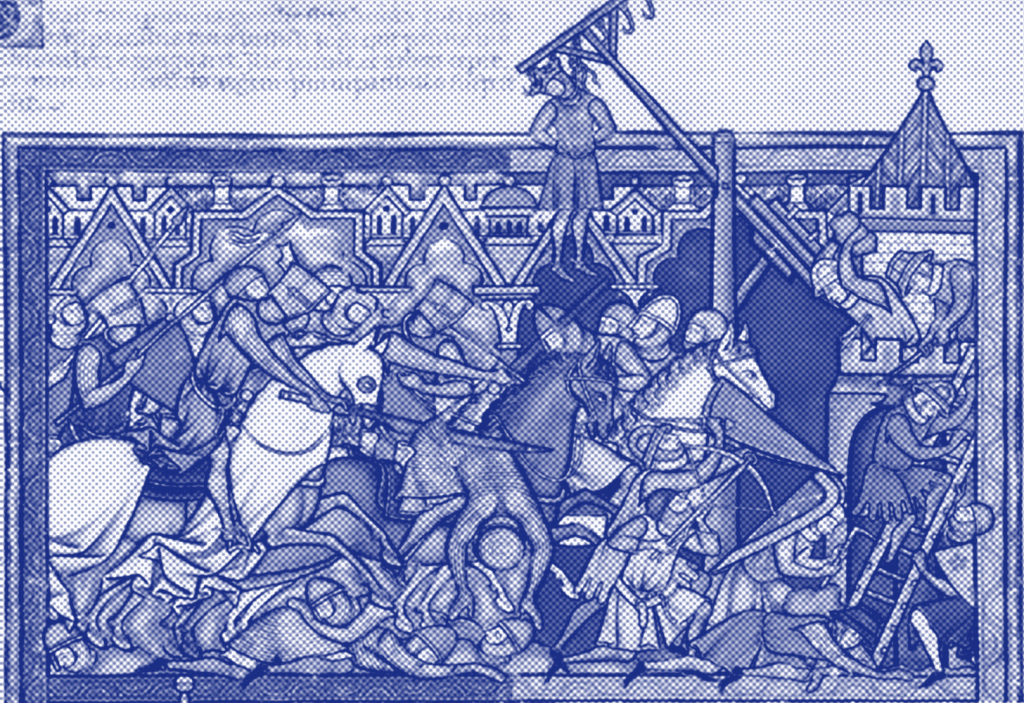

The Christians of the Crusader States often sought diplomacy. Leaders like Richard I and Baldwin IV negotiated directly (though never in person) with their mutual enemy, Saladin. These cordial relationships between men at war shed some light on their true motivations.2 Saladin famously wrote a letter to Baldwin IV, consoling him on the death of his father, against whom Saladin had also long fought.

The false image Hegseth presents is vastly over simplified. He paints the Crusaders as warriors of freedom, justice, and Western civilisation. He ignores the fact that many were not motivated by religious considerations at all, but by economic, social, and psychological factors.3 The Crusades were not the wars of pure ideology Hegseth makes them out to be. Examples abound of Christians Crusaders fighting alongside Muslims to seize cities of political or strategic importance.4

And of course, his most glaring omission: the Crusaders lost.

His heroes achieved nothing. Many Crusades followed the People’s Crusade, but none found lasting victory. Thousands of soldiers poured across Europe into the Holy Land, spilling blood for three hundred years, and at the end, they had naught to show for it. How could these people possibly be thanked for giving us Western civilisation?

Hegseth is a tiny part of a massive right-wing movement to rehabilitate the Crusades, and use them to argue that the Islamic and Christian world are locked in a natural state of religious war.

In an interview with the Guardian, historian David Perry has noted the dangers of such a position, highlighting that it was one espoused by Norwegian terrorist Anders Breivik.

This fits into the far-right’s wider obsession with the medieval period, and their campaign to misrepresent and co-opt this period of history. Hegseth is no stranger to the appropriation of medieval and Crusader imagery. A tattoo of the Crusader’s cross is emblazoned on his chest. On his arm he has the message “Deus Vult”, the call to arms attributed (likely falsely) to Pope Urban II at the start of the Crusades, a call to arms now taken up by the far-right. These tattoos, evident extremist symbols, had Hegseth barred from serving in the National Guard.

Hegseth wouldn’t be the first man in the White House to flaunt a child’s understanding of the Crusades. Donald Trump Jr. owns a rifle decorated with the image of a Crusader’s helmet.

The Dangers of Bad History

History is not, as many think, the recollection and ordering of facts regarding the past. It is a framework, and a lens, through which we view the past and shape the future.

When individuals distort history to fit their own ideologies, the results can be dangerous. When politicians do so, the results can be disastrous.

The Crusades did not give us freedom, civilisation, nor justice. Biblical verses do not provide a sound basis for territorial claims. Yet these myths persist, shaping beliefs and policy.

It is always important to question the historical narratives that we encounter, but all the more so when these are being used to build international policy. A failure to confront false representations of history risks perpetuating conflict, prohibiting peace, and poisoning the minds of the populace with myths.

A better knowledge of the past, and a more critical eye toward it, is a small step toward a just and peaceful world, but it is a step forward nonetheless.

Thank you very much for reading.

There’s so much to say on this topic and so much I’ve had to leave unsaid in the interest of brevity. One area I see as important that I scarcely even touched on, is how the views discussed above are also shaped by a specific interpretation of the Second Coming that sees Israel as a vital piece in the religious prophecy that leads toward the end times and the Second Coming of Jesus. This is a view rife among Republican voters. Maybe this is a topic I can explore in more depth in the future.

If you enjoyed this article, I would appreciate it if you sent it on to someone else who might enjoy it, or who might learn something from it.

Additionally, I’d encourage you to consider donating to Doctors Without Borders, who are doing vital and commendable work in Palestine, and who have recently tragically lost their ninth colleague working in the region.

You can also subscribe to receive emails when I post articles in the future. Thanks again.

- Norwich, John, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall (London, 1995) p. 35 ↩︎

- For a more in-depth analysis of the relationship between Saladin and Richard I, see: Chism, Christine, ‘Saladin and Richard I’ in: Bale A., ed. The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of the Crusades (Cambridge, 2019) pp. 167-183. ↩︎

- Flori, Jean, ‘Ideology and Motivations in the First Crusade’ in Nicholson, H., ed. Palgrave Advances in the Crusades (Basingstoke, 2005) pp. 15-36 ↩︎

- Runciman, Steven, A History of the Crusades, Volume III (Cambridge 1954) pp. 187-189 ↩︎

Leave a comment