This essay was originally published on Medium on January 25th 2023.

“A mysterious fire flashes from its eye,

and a flaming aureole enriches its head. Its crest

shines with the sun’s own light and shatters the

darkness with its calm brilliance. Its legs are of Tyrian

purple; swifter than those of the Zephyrs are its wings

of flower-like blue dappled with rich gold.”

– Claudian. (c. 395). Phoenix. (H. M. Platnauer, Trans.)

It certainly sounds a captivating creature in the words of Claudian. This halo-clad bird with its piercing, blazing eyes, its night-shattering crest that glows like a star, and its wings that flutter lighter and faster than the wind itself. Its a more colourful bird than the phoenix of our imagination, which is so often a bird of only a few similar hues of red and orange, not a bird of white, gold, blue, or purple. And of course whilst Claudian’s bird carried fire within its eyes and a roaring ring of flame around its head, when we picture the phoenix, we are inclined to see the bird entirely aflame.

So what do we know of the phoenix, and what can it teach us? Or perhaps more importantly, where did it come from, and why is it still with us?

It is not so unusual that Claudian’s description of the phoenix might differ so much from that which lives in our shared imagination, as we shall see that the descriptions of the phoenix through the years have been as diverse as they are numerous, and that’s not including the various modern representations and interpretations worth considering.

That said, most early records on the creature seem to agree on a few key features. Firstly, the bird is without doubt enduring; Greek historian Herodotus writes that the phoenix dies once every 500 years, and his countryman, the poet Hesiod, claims the creature lives 972 times as long as an “aged-man”. It isn’t until later that sources appear that describe the bird as immortal, or at least capable of rebirth, but these interpretations become increasingly common as the mythos of the creature develops. Finally, since its inception, the creature has been intimately linked with the sun and fire. Herodotus’ description, often considered to be the first written down, describes the phoenix as depositing the bodies of its dead forebears within the temple of the Sun in Heliopolis, Egypt, however he is careful to share that this story “does not seem to me to be credible”. Later descriptions, like Claudian’s, often claim that the bird either glows or appears aflame, and early artistic depictions almost always show the creature to possess a glowing nimbus, halo, or aureole of light or fire.

It could be the case that the phoenix was not born from fire or flame, but merely an egg. Perhaps its origins are not as mythical as we might think. Theologian Roel van den Broek notes that numerous writers of antiquity (who no doubt influenced one another) all stated that the bird resembled an eagle, with others claiming that it also bore the features of a rooster. Roman coins exist from the time of the Five Good Emperors, a little over a century after the death of Christ, which supposedly depict a phoenix, which historian R. S. Poole suggests may actually be simply demoiselle crane. The phoenix becomes a little less spectacular when we consider that its majesty may simply be a result of imperfect (although certainly reverent) descriptions of eagles, pheasants, peacocks or cranes. But what if the phoenix was born from the sun, long before it was first described on paper (or papyrus, stone, or wax)? Could it be that later writers merely searched in vain for a bird around them which matched the enchanting descriptions they’d heard before?

To answer these questions, lets return to our first written record, that of Herodotus. He begins “[The Egyptians] have also another sacred bird called the phoenix.” What was this bird that the Egyptians described and revered? One thing that does seem clear; its very unlikely that they called the bird the phoenix. Phoenix, as it turns out, is a Greek word. We will return to this Egyptian bird, whatever they may have called it, later. First, let’s see how it came to earn the name phoenix. The etymology of the name is as fascinating, as tangled, and as confusing as the history of the bird itself. It can be traced back to Mycenaean Greek, and shares a root with a number of ancient Greek words respectively meaning purple, red, dyes of the aforementioned colours, palm, date (the fruit of the palm tree), and the civilisation of Phoenicia. Tyrian purple, the colour of the phoenix’s legs as described by Claudian, also known as Phoenician red, was a natural magenta dye that became Phoenicia’s most prized export. However, our mixture is muddied further by the fact that it is unclear whether the Phoenicians earned their name from the dyes they traded, or vice versa; whether the date tree got its name from the mythical bird, or vice versa; if the bird was named for its crimson or purple hue, or vice versa; or finally, if perhaps the bird was simply named after the city-states of Phoenicia, from where perhaps the bird first took flight.

It would hardly have been inappropriate that the bird might be named for that ancient civilisation; both share a rich history of spectacle and splendour. The Phoenician’s spread their wings and soared across the Mediterranean sea, with winds in their sails swifter than the Zephyrs. They certainly burned bright, gracing the Levant with the world’s oldest alphabet, and a trade network that formed the blueprint for all those that would later connect the powers of classical antiquity. Perhaps the Phoenicians blazed no brilliantly than in the republic of Carthage, where they spawned a thorn so sharp, that it would command an army of elephants across the alps to bury firmly in the side of Scipio and the Roman Republic; Hannibal Barca. Carthage stood as a paragon of civil engineering, architecture, and commerce. Greek writer Diodorus describes it as such;

“It was divided into market gardens and orchards of all sorts of fruit trees, with many streams of water flowing in channels irrigating every part. There were country homes everywhere, lavishly built and covered with stucco.”

What he doesn’t mention, is the cothon, Carthage’s remarkable circular military port, dug out from stone and constructed within the city’s walls, large enough to house each of the city’s two hundred warships under covered berths, a feat of construction years before its time. But the flame of Carthage burned too bright. Hannibal had blazed his trail into the heart of Rome, and had almost brought the Republic to its knees through his occupation of Italy, but ultimately Scipio crushed Hannibal’s army at the battle of Zama, closing the Second Punic War. Fifty years later, the Third Punic War was concluded when Scipio’s adopted grandson, Scipio Aemilianus, put Carthage to the torch. The city was set ablaze, burning brighter than ever before, until it was finally extinguished. Unlike the Phoenix, Carthage did not rise again from its ashes. Indeed, for a long time, nothing grew from the ashes of Carthage. So total and lasting was the destruction of the city, it was long rumoured (although now disproven) that the earth surrounding the city had been salted, a ritual intended to ensure the desolation of the razed settlement, and curse those who might dare rebuild it.

Herodotus states that his Egyptian bird “comes all the way from Arabia,” once every five hundred years. Is it not possible that the Phoenix described by Herodotus was born from the brilliant flame of Phoenicia? Perhaps if we examine this Egyptian bird, and attempt to untangle the branching folklore from which the creature forms its nest, then we might know exactly what came first; the phoenix or the ashes.

As it would happen, the Egyptians of Heliopolis did worship a legendary bird associated with the blazing sun, self-continuation, and rebirth; in the form of a deity known as Bennu. Strangely enough, Bennu is transliterated from the ancient Egyptian ‘bnw’, an alternate form of ‘bnr’, meaning date, the fruit of the palm tree. Whatever this link between our blazing bird and the date palm was, it seems to have been made by multiple cultures. The Bennu was a god said to have created itself, credited with soaring across the primordial waters of the abyss, and bringing forth the birth of the world with his call. Whilst perhaps it is likely that the Bennu was not only the progenitor of the world, but also the phoenix, it’s important to remember that the ancient Egyptian civilisation was remarkably enduring, and in its maturity, was contemporary with ancient Greece. Our old friend Roel van den Broek warns us that we can’t be certain if myths of the Bennu influenced the depiction of the phoenix, or if tales of the phoenix inspired some attributes of the Bennu. So unravelling the creature’s true origins remains challenging.

This relationship with creation persisted however, and the phoenix reappears in Egypt in the early 4th century, at home in the pages of the Gnostic text ‘On the Origin of the World’. However, whilst this text claims the phoneix was present during the world’s earliest days, it lacks the role of the originator that its cousin the Bennu was honoured with. The Gnostic text focusses instead on the three phoenixes dwelling in paradise, one that lives forever, one that lives a millennium, and a final unfortunate phoenix which is “consumed”. Here in this Gnostic manuscript we also find an attribute of the phoenix which has survived into our time; the fact the creature “first appears in a living state, and dies, and rises again”. Whilst the motif of the long-lived phoenix was by this point becoming slowly established, the Gnostic text is one of the earliest examples we have of the bird being endowed with the power to return from the dead.

No small surprise then, that a bird claimed to be gifted with the powers of resurrection, detailed in a treatise by a Christian sect, might work its way into the Christian mainstream. In his collection of works on the Phoenix, scholar of Middle English literature Norman Blake points us toward a passage from the Exeter Book, one of the largest extant collections of Old English poetry. Within we find one of the many medieval connections made between Christ and the phoenix. We are told not only that the bird is “much like the chosen servants of Christ,” but also that of this bird “the fire devours the frail body… then flesh and bones the pile’s flame burns,” before the bird once more “becomes large, all renewed, born again, sundered from sins.” It’s argued that the poem not only uses the phoenix as a symbol to represent Christ, but also to represent all Christians, enduring the fiery judgement of the apocalypse.

The entire poem is a very interesting insight in to the medieval perception of the phoenix, and is well worth the read. It can be found here, starting at page 197.

It’s worth noting that the relationship between Jesus and the phoenix was probably at least strengthened, if not established, (like many other oddities of the Bible) as the result of a challenge in translation. In Psalm 92:12 of the Septuagint, the earliest extant example of the Bible written in Greek, we are told that “the righteous shall flourish like a palm-tree.” And what was the Greek word used for palm tree? Phoenix. It’s not hard to imagine that any further translators using the Septuagint as their source material may have been led to believe that the passage was referring to the bird.

Furthermore, the evolution from classical myth and “pagan” beliefs into establish Christian mythology is well established, and the phoenix would certainly have made a rather easy symbol for the early Christian clergy to accept into their systems as their influence expanded.

And the phoenix isn’t the only solar bird with a link to Christianity either. The Book of Enoch, a fascinating non-canonical book of the Bible that was sadly doomed to the cutting room floor, tells us of creatures called the chalkydri, angelic denizens of the heavens that fly around the sun and carry heat to earth. Further similarities between the chalkydri and the phoenix are few and far between, however. The chalkydri are allegedly an almost chimerical creature with the head of a crocodile and the body of a lion, a description curiously similar to that of Ammit, the ancient Egyptian goddess tasked with devouring the dead upon the banks of her like of fire. The chalkydri come equipped with the archetypal abundance of wings we expect from early biblical angels; in this case, twelve. And as a final, tenuous link to the phoenix, they are also described as purple, although whether this purple was Tyrian or not, we are left wondering.

Yet great creatures with wings aflame go far beyond the phoenix, the chalkydri, and the bennu. The images of mighty, burning avian appear in a vast number of cultures and religions across the world. Their spread and variation begs the question; how far did each depiction of the blazing bird beget, inform, or inspire the others? Or better yet; is there something innate about this mythological image that encouraged its independent generation among separated cultures?

As we travel further east, we are introduced to the Firebird, a creature of Slavic folklore, a bird that is said to glow like the flames of a fire, its feathers dazzlingly bright, even after they are removed. Is this the progeny of the phoenix, or could it be the descendant of a burning bird who migrated toward Europe from horizons further afield?

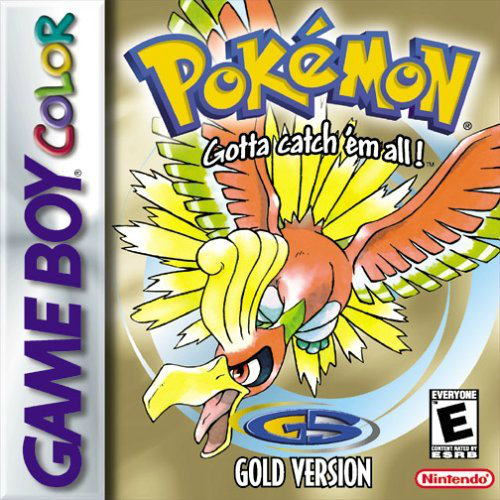

If we continue our journey, soaring south east through Russia and into the Sinosphere, we find such a burning bird, the Fenghuang. A creature that appears in the mythology of China, Japan, Vietnam, and Korea, this bird is said to be a magical amalgamation of animals; some avian (the rooster, fowl, and swallow), and others decidedly not (the tortoise, stag, and fish). If there’s something more interesting than the fact that this creature is said, like Herodotus’ phoenix, to have been born from the sun, it is the fact that his creature could well predate the Egyptian phoenix by a few thousand years. Is this the progenitor, the solar bird that birthed the others?

In Japan this creature is referred to as the Hō-ō, a bird that has earned a revered space within the mythological pantheon. It’s said to only be found dwelling in lands “blessed by peace and prosperity,” but if you’re particularly eager to spot one, you can see it adorning all manner of paintings, crafts, temples and shrines. You might not be surprised to learn that the Hō-ō is used often as a representation for both fire and the sun.

The Hō-ō brings us nicely to the topic of the phoenix in the modern day. Those of us who owned a Game Boy in 1999 might recognise Hō-ō in the Pokémon that the magic bird inspired: Ho-Oh, Pokémon Gold’s cover bird. How on earth has a mythical, flaming bird that was potentially soaring round the sun as far back as 8000 years ago, stayed with us so far in to the modern day? It seems Hesiod was right; the creature has indeed enjoyed a lifespan 972 times that of an “aged-man”.

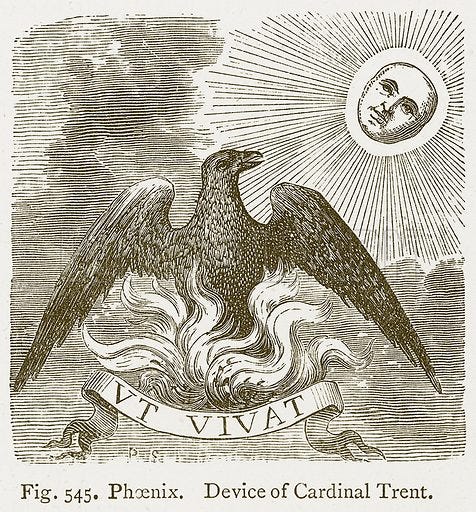

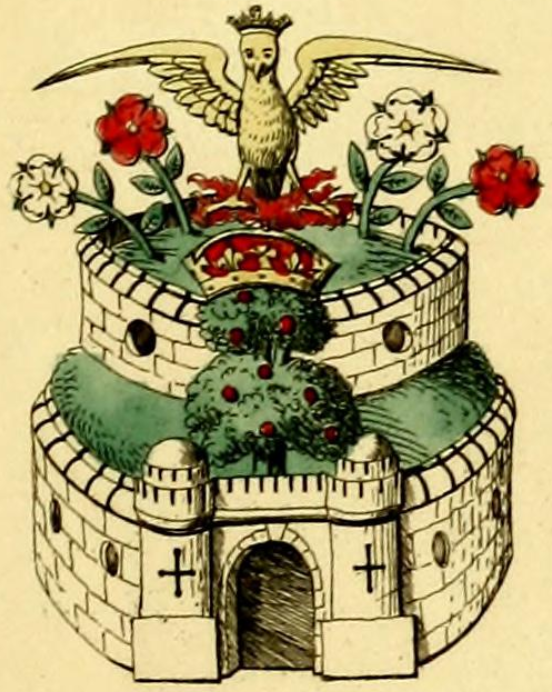

It might be easy to forget, or fail to notice, just how prevalent the phoenix still is. It’s in Arizona, it comes after Joaquin, before Nights. It’s in our literature, from Shakespeare to Terry Pratchett. Mozart mentioned it, as did Elton John. It’s appeared in more TV than is worth mentioning. From its first spark way back in the earliest days of antiquity, the phoenix has stayed with us. Into the middle ages it endured, becoming a popular feature of mediaeval heraldry. There were no shortage of noble houses, cities, and even nations that chose to depict a bird rising from the flames upon their shields and on their banners — in fact, many still do. Up until 1974, whilst the nation was still under the control of a military dictatorship, you could even find the phoenix on the front of Greek passports.

The creature has become the chosen symbol for individuals, institutions, and nations. The phoenix truly has proven itself immortal.

But why? Why is this symbol so enduring, so widespread? What virtue of the Phoenix do those who have donned it as their emblem wish to channel and emulate? It’s certainly fearsome, and no doubt awe inspiring. But one could fill an entire zoo with awe inspiring mythical beasts that have not survived the test of time. No one’s putting the Nephilim on their coat of arms. There’s no ice hockey team named after the Serpopard. No one’s stuck the Tarasque on a passport. Yet.

(Granted, these three examples have effectively penetrated fantasy games and literature, but I’ll argue that’s still not quite the same as being adopted as a national symbol.)

The answer to these questions, I think, lies in Coventry. It’s a city with a strong connection to myth and legend. Lady Godiva, an Anglo-Saxon hailing from before the days of the 1066 Norman Conquest was said to have rode naked through Coventry’s streets on horseback, to protest the harsh taxes levied by her husband, Earl Leofric. However, it is not her we are interested in today. Coventry has notably adopted the phoenix as something of a mascot. Not only does it appear on the city’s coat of arms, rising from the flames, but it also appears upon the badge of Coventry City Football Club, and (unsurprisingly) the emblem of Coventry Phoenix ice hockey team. But, unlike some of our previous examples, Coventry’s coat of arms has not been carrying the phoenix since the middle ages. Indeed, it was 1959 when the city chose to take the Black Eagle of Leofric (our tax-heavy earl) and the Phoenix as the supporters (the animals that stand to either side of an emblem) on to their city’s crest. Whilst Leofric’s Black Eagle is said to represent ancient Coventry, the Phoenix was chosen to represent the new city, rising again from the ashes. The football team adopted the phoenix on to its badge for the same reason; to represent their ability to rise again from the ashes. And what ashes were these? The ashes of 1940. On the 14th of November, 1940, Coventry became the target of the single most concentrated attack on any British city. As almost five hundred Nazi bombers flew over the city, Coventry was turned to ash. The raid lasted 11 long hours, and the destruction of the city was so total that Nazi propagandists coined the word “coventrieren,” meaning: to raze a city to the ground. The destruction touched a great many buildings, humble and historical alike, including Coventry Cathedral, which had survived since the 1300s. And as a new city rose from the ashes of the old, it chose to be guided by the flame of a bird that could do the same.

Curiously, it is this attribute that allows the phoenix itself to rise from the ashes again and again, forever burning bright in popular imagination. It is that very ability that allows it to self-perpetuate. Because the creature can bring itself back to life from destruction, we choose to keep it alive in our images. The notion of rebirth, the idea that we shall always be able to rebuild, to rise from the ashes stronger, is a notion to which we clearly feel greatly allured, and it is this ability that the phoenix represents.

We know well enough, and are reminded by Ecclesiastes, that “all are from the dust, and to dust all return.” That is to say, turning to ash is a part of life. Not only is it the final part of life, but it can happen many times during our earthly experience. We burn up very often. Many of us may be unfortunate enough to feel that our world all around us is turning to ash time and time again. And it is for this reason we venerate the phoenix. It would be very easy to become ash, and let ourselves remain that way, but often we strive to rise again. We keep the phoenix alive because we strive to be it. We too wish we could form again effortlessly out of our greatest challenges, our greatest losses. But I do not think a wise man would wish to be deathless, or even to live several hundreds of years. I do not think its longevity is why we find the phoenix so inspiring. It is merely its power to burn bright once more after defeat.

Wherever this bird first flew to us from, and whenever it first made that flight, we may not be able to say with certainty, but we have kept it alive these thousands of years for it represents something we all wish we could be — not immortal, but endlessly resilient.

Leave a comment