A rarely spoken tale from the history of Yilvorbláin

This short story was originally published on Substack on August 5th 2022.

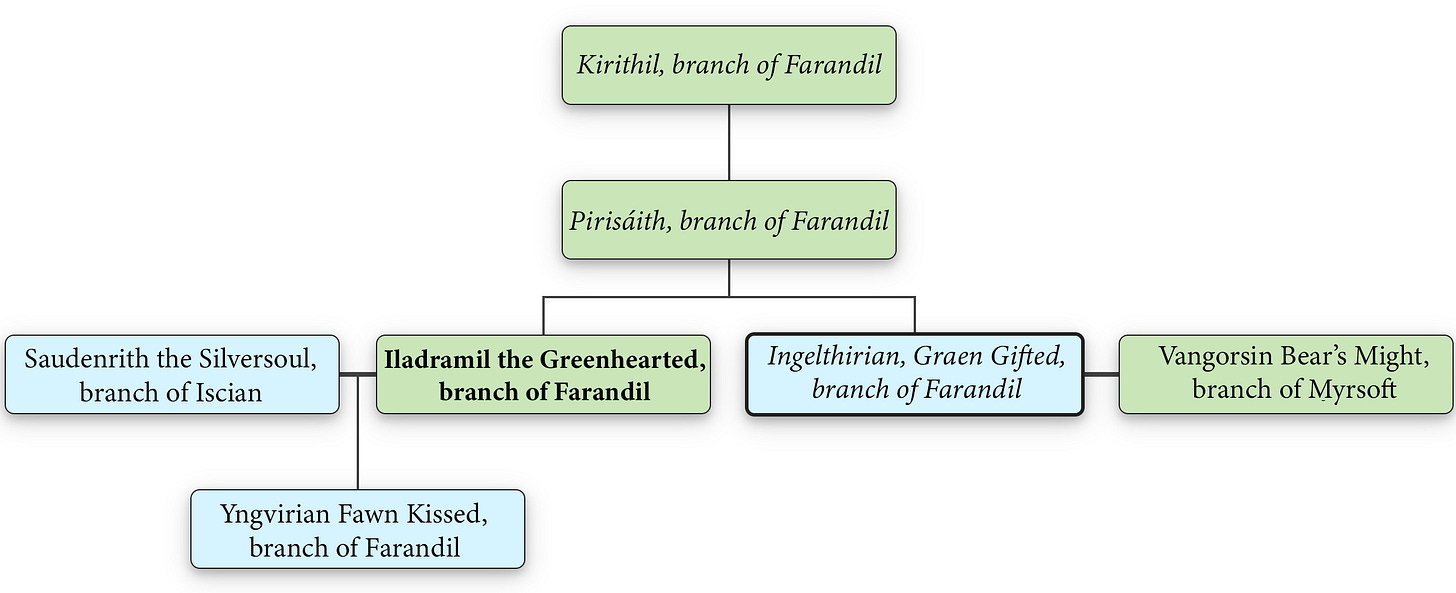

A genealogy diagram, along with notes on pronunciation of names, can be found at the end of this tale, at the bottom of the page.

It was in the uncertain days of the Third Era that the Graentree Farandil perished. Memories of the War of Reclamation had not yet gone from the minds of elves, but the War of Free Lords had yet to blight the Moorvale, for at this time neither elf nor man had even dreamed its inception. And so it was, betwixt these conflicts that assailed the hearts of men, grew a discord known only to the elves of the Yilvorbláin. Among their lush forests and their shrouded cities, an ill will was festering, blades and arrows were sharpened in the canopies’ shadows, and whispers rode upon the winds, whispers of a plot that would see a new king to the nation’s throne. Perchance so viciously had the elves fought in the War of Reclamation, that they had yet to shed this taste for blood from their tongues. Or mayhaps the other case was true, and these memories of slaughter and vitriol were now so vague in their minds, unknown entirely to but a dwindling generation, that the elves had forgotten the true bitterness of these horrors, recalling now only sweet glories.

The elven settlement of Sirilnisfaern lay to the north of Yilvorbláin, far from the great cities to the south of the nation, and separated from the borders of the Moorvale by a single thick swathe of forest. Yet so wide and impenetrable was this woodland, that those few citizens of the Moorvale who knew of Sirilnisfaern thought of it as if it were a most distant land.

The Warden of Sirilnisfaern was Iladramil the Greenhearted, scion of Pirisáith, scion of Kirithil before him, all descendants of the branch of Farandil. Firm of faith and sharp of mind, Iladramil had led his people since the death of his father, for a period now exceeding two centuries. All that knew him could fault neither his wisdom nor his resilience. Yet no matter how fervently his qualities were extolled by the people, never could he seem to escape the thick shroud of doubts and diffidence that plagued him since he had been bestowed the Warden’s spear.

The Warden’s sister, Ingelthirian, had also been a leader of great renown, possessing wisdom that exceeded her brother’s and an unmatched connection to the Graentar that had earned her great veneration. She took from her mother in that regard, she delighted in sending messages upon the wind, listening to the rivers, and traversing the forest by way of passing through and within the trees. She did not share her father’s skill or passion for diplomacy, but yet his court still sought her often, for even in domains she was not well versed, her sagacity was illuminating. In her youth she had been wedded to Vangorsin, Warden of Aertinhilm. For many years did the two houses, and by extension their wards, enjoy great equanimity of a degree remarkable even for the cities of elves, who mostly enjoyed much harmony since the final days of the Reclamation. For years Iladramil and his brother by marriage displayed a firm alliance, their settlements distant but in regular coalition. But many years had passed since that concord, and Ingelthirian had perished, victim to a foul blight that had rid her of both her youth and wits. A disease so loathsome had assailed her that not even her vigorous connection to the Graentar, nor the best efforts of both her husband and brother, could save her. From that point on, the two Wardens descended into a destructive bitterness, both driven to blind wrath for one another by their grief. Neither blamed the other for Ingelthirian’s unjust end, but their hearts proved too wrought with anguish for them to ever return to their cordiality. When Iladramil thought of Aertinhilm, he heard the wails of his sister. When Vangorsin thought of Sirilnisfaern, he heard the screams of his wife.

With Ingelthirian’s passing, but two descendants of Pirisáith remained; Iladramil, and his daughter, Yngvirian, born to him by his wife, Saudenrith the Silversoul. Yngvirian was now a woman in her second century, who possessed all the insight and careful discernment of her father, yet was free of the voracious self-doubt that cursed him. Rather she was graced with an unconquerable alacrity, a zeal which was cherished by all the elves of Sirilnisfaern. She was quite singular in appearance too, with eyes the colour of a winter’s sky, her face framed by flowing hair that smouldered with fires of autumn. These were features quite rare among the elves of Yilvorbláin, almost all bearing hair and eyes the tone of chestnut. Fawn Kissed they called her, for from her first days she embodied the aspect of the doe, an image of pure grace, wide eyes burning with a percipient curiosity. As if to further accentuate her rarity, she would adorn her hair with polished stone beads and feathers of beautiful hues, a fashion that had long fallen from favour in the nation’s north, though had oft adorned the locks of her aunt, the Warden’s sister.

And thus it was only Iladramil, Saudenrith and Yngvirian that still called the great hall of Sirilnisfaern their home. And on the eve of great turmoil, Iladramil felt his domain almost threatening in its emptiness, as if he were watching life and laughter drift away from it. Two omens would soon be delivered to the Warden, and his city faced peril from both within and without. At this time, it was felt by many that the settlement may soon be swallowed by the darkness that pervaded it.

The first omen followed snowfall, his arrival heralded by a blizzard that engulfed the forest for near a moon, itself portentous in its indelibility. Soon after the snow had ceased falling, yet whilst it still blanketed the realm, a rider came upon a great black bear. Bearing no escort he rode alone, lumbering through untold bitterness, with a message, and a warning, for the Warden. His approach was witnessed by many, for he made no attempt at stealth. Iladramil, gazing from a vantage point within his halls, watched, troubled, as the figure approached. A cape of grey fur mantled him, but there was no mistaking the harbinger. Hair the shade of night sat knotted upon his head, the sides shorn to the flesh. At his hip hung a blade, its scabbard pitch leather, its curved hilt a brilliant silver. The rider was none other than Vangorsin, Warden of Aertinhilm.

“Why does he not send his message through the mouths of the forest?” asked Yngvirian, who was stood beside her father on the balcony.

“It is graceless of a Warden to send any message of consequence on the tongue of an animal. For announcements of great import, an elven herald is sent. But seldom is the envoy the Warden themself. I fear this betokens ill news.”

Vangorsin was received cordially, a reception prepared for him befitting family. After their meal, Iladramil dismissed both his advisors and his guards, and with the two alone in the Warden’s court, Vangorsin delivered his message.

“Rikaeth Sylmaris is not long for the throne. A new king awaits Yilvorbláin.”

Risen from his chair, Iladramil bellowed his retort. “You come to my halls to insult our king? To besmirch the son of Doralmin the Elf Guard? It is to the Sylmaris line we owe thanks that our nation still stands.”

“And it will be to them we will owe thanks when it burns. Rikaeth lacks his father’s foresight, yet carries all of his impulsiveness.”

At this, Iladramil sank, his aspect solemn. “The birds carried hints of these rumours, that Gentiris coveted the throne, but I thought better of you than to be seduced.”

“Do you not hear the nation demand it? The forest and the sky demand it. Even the Graentar itself demands it. Or have you grown deaf to its voice also?”

The Warden did all to veil his fury. “Do not be so bold as to insult me so in my own halls, Vangorsin. We enjoy peace under our king, those who demand turmoil forget its true colour.”

“We know nothing of peace and all of submission! Rikaeth besmears his own father’s legacy by parlaying with the humans of the Moorvale! Allowing them to gaze upon our cities? Permitting our kin to live among them?”

“Can we forever live in seclusion? Do the sagas not tell of a distant concord enjoyed with the humans?”

“A concord defiled when they expelled us from Eisyaal’s gifted lands! There were days long past that Einsyaal was visible in every corner of Garriael. We neglect Its gift of land by allowing it to slip from our hands. We dismiss Its gift of the Graentar by turning to book magic. Soon It will discard us entirely, if we continue our disdain.”

“You sully Einsyaal yourself, fool, by even propounding war in Its name! I will not hear of it. We tend the land we have with great care, and our nation is a haven for it, a nation you would seek to disembowel. And you dare disdain book magic, oh hypocrite you, whilst you wear a sword bearing glyphs engraved by my own enchanter, glyphs lifted not from the Graentar but from a tome! How dare you regard it as a pursuit impure when it was to grimoires you resorted when my dear sister fell ill!”

The conversation bore no fruit. Old fires were stoked anew. Vangorsin departed, and spoke thusly, “You are wrong, Iladramil. You are so blind that dawn comes and you are convinced it is still night. I am the herald of opportunity. Fly the banner of Gentiris. Champion our new king. Furnish our ranks with your men.”

“And so, you have come to my court to ask me to join your hopeless cause?”

“No. I come to tell you it is your court no longer. Declare yourself standard bearer for our new sovereign, or declare yourself foe. You have a half moon to deliver me your choice.”

With his ultimatum he withdrew from Iladramil’s halls, returning through snow-blessed forest upon his ursine mount. Hurriedly, Iladramil summoned his advisors, and in his court apprised them. The mood among the gathered elves was dour. To all it now seemed war was inevitable, but still none spoke of conceding to Vangorsin, nor of turning on their king. Gentiris and Vangorsin commanded great armies, forces it was doubtful Sirilnisfaern could withstand. Iladramil’s conscience dictated he stand by his king, but he well knew that decision could cost his people dearly. The future appeared to them murky and foul, and not one of the elves present could think of how peace may be retained. Not even Beigrith, wisest of Iladramil’s advisors, and a cherished companion also, could cast clarity upon their dismal fate. The Warden retired, to consider the dilemma alone.

The second omen had been long festering, but following Vangorsin’s threat, it revealed itself to Iladramil quite plainly. Since the days in which the first elves were born from their Graentrees and received the gift of Garriael, Farandil had stood proudly within one of the groves that veiled Sirilnisfaern. In these days so far removed from the Gifting of Garriael, it was rare that elves knew anything of the Graentree from which their ancestors had sprung, not least their locations, instead carrying with them only their name. But the elves of Farandil’s branch had been blessed with good fortune, for all the descendants of Farandil’s first elf had called what was now Sirilnisfaern home, thus their Graentree had never succumbed to history’s tangled limbs, as was the fate of many others.

Farandil was a Graentree most astounding, and around it lay a tranquil clearing, within which both elf and beast found serenity. Within this clearing, under the meandrous branches of the stout yew tree, it was said no elf had ever shed blood nor tears, and never had any creature of the forest been seen preying upon another. It was in this place the elves of Sirilnisfaern felt closest to the Graentar, greatest of Einsyaal’s gifts. Here within this revered glade, it was as if the unseen threads of the Graentar were manifest, and one could sense them linking all things, connecting elf to forest to creature to all and to Einsyaal Itself. Most valued of all was the voice of the tree, which carried the whispers of the departed elves of Farandil’s branch, allowing those who still lived to reach ancestors and loved ones lost. But for two moons now the yew’s leaves had begun falling, and littered the snow around it, a sight which none recalled seeing any year before, nor of ever hearing in any tale nor saga. And as the tree succumbed to its indiscernible blight, the folk of Sirilnisfaern shared its plight, and fretted in anguish.

It was among the fallen leaves and snow that Yngvirian found her father, two days after Vangorsin’s warning, knelt alone before the great yew tree, head clasped in his palms, weeping. As she lowered herself beside him, he deigned to turn to face her, ashamed he would be seen so desolate. He stifled his grief to address her, remaining on his knees at her side. “As these eternal leaves were falling, I could sense the Graentar drifting, and the whispers of the tree grew ever more hushed. I did not dare believe that a fate such as this would befall us, but I am afraid it has; I can now but hear the faintest murmur. Our Graentree is soon to die.” With her hand on her father’s shoulder, Yngvirian gazed at the tree with both sorrow and reverence. “And what of these murmurs father? What words do you yet receive?”

“My own father is still here with me. I hear him, although I hear his weakness. I can hear him less each passing moment, his voice becomes one with the breeze in my ears. Less do I understand his message, and less it seems he comprehends my replies, although I doubt he even hears them. I must wonder what foul misdeed I have committed, that I am forced to endure this punishment.

No longer can I hear the voice of ancestors before him, lost to me entirely are they. Even Kirithil, father to my father, with whom I never shared the mortal realm, yet guided me my entire life, is voiceless now. I cannot even sense him here.

Perhaps Vangorsin spoke truth to me. Could it be that even Einsyaal no longer esteems me? Has It withdrawn Its gifts, severing me from the Graentar? Severing us all?”

“Do not set store by his words, father. He seeks only to undermine your confidence, to convince you all is lost.”

“I am uncertain there is much confidence left he can undermine. I feel a wretch. I feel myself lost, incapable of relying upon my own counsel, now I am without the guidance of my ancestors.

For centuries I misspent my occasion to learn from them. And only now that this chance has fleeted, do I realise how much I left unsaid, how many questions shall wilt unanswered.

It was their guidance that shaped me. Near all I have learnt, I learnt from their direction. It was my mother’s father that taught me to craft a bow from elm. It was my father’s mother that taught me the songs of all our forest’s birds. My father’s father, Kirithil, was bannerman for the good King Doralmin Sylmaris, Elf Guard. For years he fought valiantly in the War of Reclamation, bearing swords shoulder to shoulder with kin from all of Yilvorbláin. Leading the soldiers of Sirilnisfaern, he held back Hymar and his Aetherwulfs from our borders, risking his life to defend our people. Alongside Virnelis Balmaer he stood in the battle for the Fields of the Dead, for days and nights they waged bloody war against Ice King Skole and his invaders, until finally he was forced to watch Virnelis fall. So much did my father’s father know, so wise he was, so keen of wit and broad of heart. He was all a leader should be and everything I can nary even hope to embody. Great elves have given everything to pass this fine settlement to me, and it is in my hands that I must watch it turn to dust, tarnished embers slipping through my fingers. Not since those dismal days of war, since the days of Skole Grief Forged Een-Sindarn, has our blood known a darkness such as this.”

At his final word, a delicate snow began to fall again, drifting lightly through the glade.

“I weep for your loss, father,” replied Yngvirian, “To lose these untold lifetimes of wisdom is a pain almost too great to bear. But Sirilnisfaern needn’t turn to dust, and it shall not.”

“I cannot betray my king. Such dishonour is everything my ancestors fought against. But if I refuse to submit to Vangorsin’s demand, if I do not fly the banner for Gentiris, then they shall bring their combined might to bear upon our city, a might we shall not survive. We would be slaughtered. And for what? My stubborn adherence to lost ideals? I cannot dispose of the lives of our people like so.”

Yngvirian’s heart ached to see her father’s tortured facade. The dilemma was devouring him. Not only did the loss of his ancestor’s voices assail his soul, but also the stark reality that he must now face this horrendous plight alone. Without their companionship he felt lost. Without their guidance he felt impotent. Devoid of both, he was distraught. It was as if he had been enveloped in a bleak cloud of fog, impenetrable and foreboding, from within which he could not see out. It had trapped him, allowing him to gaze upon nothing but the darkness that lay directly before his eyes.

“I cannot bow to Vangorsin’s demands. But I cannot leave our people defenceless.”

“Must we, father? Can we not rally our fighters? We have Graentar mages well versed in their skills. Your guard are peerless in their skill. Would not other Wardens heed our call for aid? We might yet summon a resistance.”

Iladramil sunk lower, bowing his head before the yew. “Your optimism brings me some respite, my child. A glimmer of hope can be found in that you retain resilience. But alas, I feel it is misplaced.

“My guard are masterly, yes, but they are of such small number, they cannot protect us all. I have failed our settlement, and I have failed them through inaction.” Tears streamed down his cheeks. Within him raged a storm unparalleled. “I have been so gifted, so blessed to have received all I have in life, a true fortune of knowledge. But I realise now that though I have learnt so much, I have done so little. I have lived many squandered years.”

“Nay, you have done much! You gathered such knowledge from your forebears, you have created a prosperous society, balanced in its appreciation for the Graentar, warcraft, art, diplomacy.”

“But in none of those realms have I excelled! I have toiled, yes, but aimlessly! I have been as a blind pilgrim, leading our people racing forward, yet failing to decide upon a path, realising too late that they have all been barred to me. You speak of our warriors, and of alliances. If I had but acted as my father, I could have strengthened the unions he fought tirelessly to build with Wardens near and far. If I had acted as my father’s father, I could have turned our warriors from humble rangers to a mighty force. Alas, I have let us slip into weakness and isolation. And now for these sins, I must pay.

“Father!” he screamed at the yew’s great trunk. “Why must your voice be taken from me now? Why can I not hear you when I need you most?” Echoes of the Warden’s lamentation filled the clearing with sorrow.

And then total silence descended upon the Graentree. Father and daughter knelt side by side in its shadow, until the sun set, and all was shadow in that glade. Finally, Yngvirian addressed her father. “There is no impasse too great to summit. You have told me the stories of Kirithil, father to my father’s father, and in them I hear of a man who defied great odds. If he could lead our people in the defence of our city against Hymar Wolf’s Fang, and face Skole Grief Forged Een-Sindarn upon the Fields of the Dead, then you, father, can rise against Vangorsin, and defy the greed of Gentiris.

“You race, you surge forward, never ceasing nor resting. Lend yourself peace, I beg. Einsyaal does not punish you, it is you who tortures yourself. Do you not hear the good graces our people shower you with? They would follow you toward any peril.” The snow had ceased falling now, and all was still as Yngvirian spoke. “You betray them not. Given the choice, they would die defying those who seek to oust our king, rather than live in the ignominy of serving a usurper.”

Iladramil thought for a long time. He pressed his forehead into the snow, and then stood.

“It is surprising. Even the most trivial of my losses rend my heart. It was my father who first played me the lyre. I would come to this tree on warm days, and speak to him of new songs I had heard, carried by minstrels from afar. I shan’t get that chance again.

“But it matters not what has fleeted. You speak truth. I cannot invite new pain upon us all by lamenting losses that cannot be changed. I shall go to Vangorsin. I shall tell him I will not kneel.”

Leaving the glade, he rested his palm upon the bough of the tree. No whispers could the Warden hear. He uttered instead, his own. “Thank you. I shall squander your gifts no longer.”

On the following morning, Iladramil gathered his closest advisors in his halls. He summoned Dornil Moon Given, branch of Scindis, captain of the Warden’s rangers; Myrad Bright Mind, branch of Aescelia, the Warden’s favoured sage and chosen enchanter; and Beigrith Wood’s Will, branch of Orlyg, the shrewdest of all Sirilnisfaern’s ambassadors, who had served Iladramil’s father also. Within the hearts of these three burned a love for their city and its people, and also an unwavering commitment to their Warden. A great tension lurked among them as they awaited Iladramil’s announcement, uncertain if their liege would side with the King for the sake of honour, or with Vangorsin, perhaps ensuring safety, but at the cost of a concession most cowardly and foul. “We have now twelve days to deliver Vangorsin a reply,” spoke the Warden. “It is at least five days ride to Aertinhilm, if a sturdy mount is chosen. Five days to return. I shall go. I shall tell him our city shall not kneel.” Elation graced the gathered elves, but only briefly.

“My liege,” spoke Dornil, captain of the rangers, “Although heartened by your choice, I cannot abide by you making this journey. If we are to resist Vangorsin and Gentiris, your people need you here to guide our effort. We will require your counsel in the coming preparations. Have your message delivered in the mouth of a bird, sir.”

“I cannot. In these dark days, integrity’s value is immeasurable. It falls upon me to demonstrate a true Warden’s nobility. Such a message must be delivered by an elf. Even Vangorsin, so void of honour is he, delivered his vulgar threat himself.” All knew there was no convincing the Warden, for so bound to honour was he, he would not dare send such a fateful message in the mouth of an animal, even to his most wicked adversary. Then Myrad, master enchanter, spoke, “Iladramil, you speak truth indeed, that Vangorsin acts without honour. Surely then, you must see also that he is not above attacking you within his halls when you bear your message?”

A great, imposing silence settled among the gathered elves. Finally, Iladramil replied. “I can see it, Myrad. And that says much, for now I can see little. The paths ahead of me shrink and the forest grows dark. But yes, I see death ahead of us, and it stalks behind us too. Blood shall spill, and if not mine, then Sirilnisfaern’s.”

Beigrith, that master of diplomacy, could hold his tongue no longer. “Enough!” he bellowed, silencing Iladramil’s lamentations. Known for his even temper and level mind, his outburst astounded his peers. With his mind gathered, he spoke softer now, fearing greatly that he had disrespected his Warden. But Iladramil merely gazed at his companion with frozen, iron eyes, seemingly without offence at Beigrith’s sudden eruption. “My liege, enough. If war is unavoidable, then so be it. But Sirilnisfaern will not march to battle without its Warden. Gone Farandil may be, but its branches converge within you. My apologies, Iladramil, but you cannot continue its legacy with blind sacrifice. That is, if war is unavoidable. But I deem it not so. Blinded by greed Vangorsin may be, but he is not without sense. I can appeal to his cunning. If he can be convinced that conflict would conclude in favour of the King, then he shall abandon his plot. He is an elf blinded by the promise of power, and he fears a fall from grace greater than he does any foe. If he sees his lost cause as futile, he will not dare march on Sirilnisfaern, nor upon the capital. Without his support, Gentiris too will falter.”

When Beigrith spoke it was as if he sung; not thanks to his cadence nor tone, but his words lifted from him with a grace that none found disagreeable. Truly, he had been well selected for his position; he was a diplomat without peer. His stern advice landed sweetly in the ears of his companions, and Iladramil answered with a single, heavy nod of his head. “So be it,” spoke the Warden. “In your mouth may this message be carried: We shall not kneel to greed. We shall not kneel to betrayal. Sirilnisfaern stands with the King. And stand proudly, we shall.”

Oft was the moon of Dengirmaan one of calm, a time for thawing, of both moods and frost. Save perhaps for the short celebration upon the Discourse of the Fir Tree, the cities of Yilvorbláin, and the elves within them, spent this period still in the gentle yet ever-present grasp of a light hibernation. However, this year, the Discourse was marked with neither feast nor dance, for this Dengirmaan saw Sirilnisfaern distracted, seized by an unusual measure of activity, as if it were some secluded nest or hive suddenly awash with furious creatures.

Iladramil had wasted not a moment. Each warrior and ranger sworn to the Warden had received their summons, and indeed any elf capable of wielding bow or spear had been convened to stand alongside them. Scouts coursed through the wilderness like tangling vines seeking sunlight. Retinues of emissaries, apprised of the dire need, were sent racing through the forest to summon what allies they could from settlements near. Iladramil’s faith in his chief ambassador was unshakable, but he was not so imprudent to not prepare contingencies, lest Beigrith fail to rid the blinded Warden of Aertinhilm of the shroud of greed that had assailed his wits and foresight. If Vangorsin so hungered for war, hungered for treason, against all better judgement, then Iladramil would not see Sirilnisfaern crushed under heel.

Upon the nineteenth day of Dengirmaan, five days past the unmarked Discourse of the Fir Tree, the Warden was casting keen eyes over a bevy of his warriors. He had arisen early so he might oversee their training, as was his wont. The warriors of Sirilnisfaern, although not famed for their warcraft, were nonetheless a fearsome sight. Glimmering silver plates clad their shoulders, and many trained, and often bravely fought, with torsos exposed, displaying swirling tapestries of markings upon their flesh, each representing a feature of prowess, ancestry, or rank. Around their heads were wound dark cloths, a strap above the brow, and a hanging veil obscuring the nose and mouth, so that nought was visible of a warrior’s face save their eyes, which were typically surrounded by a dark warpaint fashioned from soot. Beyond this they adorned themselves with feathers, foliage, and furs of various kinds and colours. Seen in this way, it would be clear to any observer that the elves were not dwellers within, but rather a vital component of, the forests which they called their home, the forest they claimed had been gifted to them aeons ago by Einsyaal. All carried bows upon their back, and those with enough fortune to possess a sword kept these blades hung from their hips. Whilst perhaps not as tremendous in appearance as warriors from cities of great wealth, or of eras now forgotten, the defenders of Sirilnisfaern possessed skill most enviable, trained excellently were they in the art of the bow, and some in bladecraft also.

Gazing upon them as they trained, Iladramil felt pride swell within him at his forces, but he would not let this dim spark of hope dispel his doubts. His opponent was cruel, and the enemies of Sirilnisfaern could soon be numerous. Deep was the sensation of futility that refused to release him. Defending the city would be no easy task, nigh impossible against the combined forces of both Vangorsin and Gentiris. He was aware how heavy was the weight of responsibility, now carried by Beigrith, who alone was tasked with leading Vangorsin to gaze upon the light of truth and reason, and away from war’s dark allure. The warriors were training doggedly. None could question their loyalty nor skill. Yet Iladramil prayed. He prayed that their bows would not need be trained upon fellow elves.

A heavy cloud ripe with the promise of snowfall hung above Sirilnisfaern, and the clearing in which the warriors trained had been cast in strands of thick shadow, through which but a few determined beams of sunlight penetrated. Arrows loosed and blades rung under the sky’s grey veil. Here, Iladramil was awoken from his daze by Dornil Moon Given, captain of the rangers, who had appeared by his side. Behind the captain stood his steward, a downcast look upon his face. Dornil himself wore a look of consternation too, for his Warden’s anguish did not go unnoticed by him. As he addressed Iladramil, the cloud above broke, surrendering a gentle spell of wandering snowflakes. “A pair approach, my liege, bearing the crest of Aertinhilm. Messengers from Vangorsin, so believe the rangers.”

“Let us prepare a reception in the great hall. We shall host them with grace, whatever their business.”

Dornil’s aspect darkened. “My liege, they travel not for your halls. Their destination appears to be Farandil.”

Now the Warden’s countenance matched the captain’s.

Under the shadow of the great yew’s web of barren branches, adorned with gentle snowfall, two men stood, gazing upon the stout, yet lifeless trunk of Farandil. They did not turn but held their inspection as Iladramil arrived, flanked by Dornil and Myrad both. Anger hung to the Warden’s voice as he greeted the pair, yet he maintained his dignity.

“Branches guide you, brothers. Forgive me, but I did not expect to host guests under the boughs of my ancestor’s tree, especially given the inauspicious relationship our houses maintain.”

The pair now faced the Warden, but they uttered naught. Iladramil asked after their liege, Vangorsin, inquired as to how his message had been received, and how fared his dear friend Beigrith, and where the good elf was now. After some silence, the messengers strode toward the Warden as one, stopping but a few paces from him. Dornil clenched his fist behind his back. The captain had not dared bring his rangers with him to the glade of Farandil, for all knew it had in all time been free of bloodshed, and to defy the clearing’s eternal peace would be a most prophane transgression, yet still he feared these heralds of his Warden’s enemy would not respect this fact in kind, and may chance to strike Iladramil, for perhaps they had been sent not as messengers, but murderers.

Finally, one of the silent strangers delivered their message. “Your terms are rejected. Warden Vangorsin takes it as nothing other than insolence that you would send a messenger after he had made his terms so clear.”

Again returned the persistent futility, awash with fury in the Warden’s heart, mired by a great sense of loss, a loss of yet another opportunity, lost to this same unending torrent of dire fortune. Myrad approached, rested a hand upon his Warden’s shoulder. Iladramil’s disquiet was radiating from his very flesh.

The messenger continued. “Warden Vangorsin fears you need reminding of his terms, since you failed to heed them at first hearing. He had kindly afforded you a half moon to submit to his Wardenship, but your impudence has been taken as refusal. From this day our houses share no bond. Withal, Aertinhilm declares Sirilnisfaern as enemy, and you, Iladramil so called Greenhearted, branch of Farandil, as traitor against the new King of Yilvorbláin.” Silence followed the messenger’s final word, so total that the elves could hear the snow drifting to the ground.

Dornil came to the Warden’s side. If the messengers brought no fair tidings, then he presumed his suspicions were well founded, and they intended to instead bring harm to his liege, here in this markless clearing.

“And what then of my ambassador?” asked the Warden. “What price does your liege demand to release the first prisoner of this tactless conflict? Or perhaps he expects me to return you to him as trade?”

“You needn’t pay a ransom, Warden of Sirilnisfaern. He is yours.” Relief greeted the three at this statement, and even Dornil, who found his hand resting upon his pommel despite his intentions, found the unease leave his bones at this admission.

Iladramil’s voice regained its characteristic evenness, met with this thin glimmer of hope that pierced the darkness. “Good. I am glad that even in these times, your Warden does not prove to be utterly without sense. In this case, as token of my goodwill alike, you are free also to return to your liege. Tell him his terms are understood. If it is war he wishes for, Sirilnisfaern stands against him.”

The messengers glared at the Warden with gazes alight with bitterness, even at his kindness. Then the same messenger spoke. “Of course. Here is your ambassador, do with him what you will.” And at that, his silent accomplice retrieved from a satchel at his side some strange object, and held it hanging from his hand, suspended by strands of thick grey hair, before tossing it to the floor at the Warden’s feet. It took Iladramil but a moment to identify the gore-caked object as the head of his dear friend and ally, Beigrith, who’s lifeless eyes now stared back at him from the severed head, so cavalierly tossed upon the snow. His gaze tore into the Warden and seared his heart. Iladramil roared in pain, a roar so wretched and deafening that it is said even the trees of Sirilnisfaern quaked at his wailing. Here he was lost, seized by some great power, some influence not grasped nor understood, his pain a conduit for the greatest misdeed to befall Sirilnisfaern. His roar ceased as swiftly as it had begun, although its echoes are felt still today. For then he was upon the messengers, his sword somehow suddenly within his grasp, held aloft. With nary a word he was before them, and he slew them where they stood, under Farandil’s great boughs.

Then he retired to his quarters, where he wept. He wept not only at the loss of his dear friend, but also at the blood that had spilled in the sacred glade of his forebears, which had been unsullied by slaughter until that day. He wept at the future he foresaw. He wept at the desperate fate of his people. He wept at the desolation of his heart. It is said then he spoke these words; “The world becomes hate, and now I have become hate also.”

Blood stained the roots of Farandil, and stained the Warden too. Wanting to rid himself of this baleful mark he felt he bore within, Iladramil spent the following days denying himself both rest and respite.

On the final night of Dengirmaan, as the waning moon’s thinnest glimmer cast Sirilnisfaern in an argent glow, the Warden espied a gift traversing through the trees of his city. Donned in diverse regalia vandalised by harsh travails, a band of messengers came forth from the darkness. Some of these weary travellers were emissaries of his own, clad in familiar garb, others, unknown to him, assumed the raiment of settlements both near and far. Among them all he discerned one clad in the rich, verdant habit of the King’s own ambassadors. “Lo,” whispered the Warden, watching from that vantage point atop his halls, “perhaps I have but one blessing left.” A murmur was uttered in reply, startling Iladramil, for he had believed himself alone. Behind him stood Yngvirian, Fawn Kissed, eyes rippling in the moon’s lustre. “Behold father, not all is lost. As yet, we have allies who shall stand at our shoulder, and we remain in the good graces of King Rikaeth, son of the Elf Guard.”

The Warden nodded, and for the first time since that foul omen had arrived riding a bear, he smiled. His heart lifted, he was reminded of a tale, which he retold as his daughter listened. “A memory was delivered to me this night. A story shared by my father. It concerns a great king of elves, from the days of the First Era, when Garriael was new, and elves lived that remembered sprouting from their Graentree.

“This king was in the midst of war, and it was in this war that he was crowned, for a foul battle had taken his father. When his father passed, all his subjects were astonished to see not a mote of regret upon their new king’s face. No tears did he shed, nor did he lament. This, he could not grasp. He had loved his father dearly, and learnt all he had under his guidance and care, yet weep he could not.

“Summoning worthy loremasters, bards, and ovates alike, he demands he hear good tales of his father, willing that these might stir his stone heart and summon forth his sadness, but to no avail.

“Thus, the young king subjected himself to many tortures, all attempts in vain to elicit a symbol of the sadness he felt riveted within him. Convinced now he was victim of some maleficent spellcraft, his hunger for grief grew great measures. So desperate was he to rid himself of this heartache, yet still so unable to summon as much as a single teardrop, he hunted woe however he could.

“The king’s quest for desolation isolated him, for his exploits became increasingly fraught with danger and foolishness, as he fought to inflict upon himself a pain that might finally move him to the tears he so craved. Yet even as his closest confidants and his dearest loves assayed to avoid him, even abandonment could not bring forth his liberation.

“So daring his search for pain became, he was known to lead his soldiery to battles of odds so egregiously unfavourable. And it was in the fangs of one of these hopeless skirmishes that the king was flung from his mount, surrounded by foes, their weapons brandished, prepared to land the blow that would win them their victory. Here he prepared to perish. Yet even at meeting Kobara’s embrace, preparing to depart to the land where Summer ceases not, the king felt nothing. Still no tears did he cry.

“But death’s embrace did not close around him. Nay, rather he was saved, saved by allies he did not imagine would risk their lives for him, for he presumed they loathed him so, so insular and injudicious had the king become.

“Finally, as he was lifted by his bannermen, his wounds tended, with victory at hand, he wept. Upon that vile field he witnessed solidarity’s bounteous gift, and he wept. Suffering could not achieve what kindness finally managed, and then that good king learnt what I see now. Suffering is but half of life, and no suffering is so great that we should cease to seek the light. Never consign oneself to dwell in darkness, for in time its shadows dull. No night is so dark that a dawn cannot follow. A new day will always dawn, and with dawn comes hope.”

Yngvirian listened, and she marked her father’s words well. The dawn he spoke of would soon be upon them. The old moon was slimming to nothingness in the darkening sky. In this new darkness loomed a future Iladramil was right to fear, for the sudden and spiteful terrors of the Ascension of Gentiris would soon be upon them. But indeed, a new day was dawning in the story of Yilvorbláin, and with dawn comes hope.

Thanks for reading Tales from Garriael. Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

For simplicity, only individuals who are mentioned by name within The Last Days of Farandil are included within the geneaology diagram.

Italicised names represent individuals deceased during the period in with The Last Days takes place.

A note on pronouncing words borrowed from the Yilvorbláin language;

- The digraph ái is pronounced like the y in the English word lyre, spoken with a gliding vowel. Thus the áin in the word Yilvorbláin is pronounced not unlike the English word iron.

- The digraph ae is pronounced similarly to the ai in the Enlgish word pain, but once again with a gliding vowel, voiced at the roof of the mouth. It is somewhere between the sounds made by aye in the common English pronunctiations of prayer and layer.

Leave a comment