This essay was originally published on Medium on August 23rd 2023.

Bart: Well, if your soul is real, where is it?

Milhouse: [motions to his chest] It’s kind of in here.

And when you sneeze, that’s your soul trying to escape.

Saying “God bless you” crams it back in!

[gestures up his nose] And when you die, it squirms out and flies away.

The connection between life and breath can be found within cultures and languages across the globe and through time.

But how did it develop, and where can it still be found?

Breath’s Value

Anyone who’s made a conscious effort to live without breathing can attest to just how difficult of a task it is. Not only is the process vital, but of all of the procedures our bodies perform to keep us alive, breathing stands out as one over which we exert a surprising amount of control.

We can’t keep our neurons from firing, we can’t pause digestion, and we cant stop our heartbeat, short of entering some kind of ultimate meditative stupor, or… well, dying.

Yet when it comes to breath, we can take the reins for a while, and wield some minor command. It stands alone as a vital process that we can (to a degree) steer.

Given the importance of breath, its necessity for human life, it is no surprise that cultures across space and through time have developed a symbolic and sacred relationship to the breath.

The connection between life and breath has become firmly entrenched within our ways of thinking (rightly, and predictably so), but what might be less obvious (depending on the language you speak), is how firm this connection appears within linguistics. It’s this connection I’ll try to illustrate today.

Those of certain religious inclinations might already be quite familiar with this link. The Abrahamic belief (found in the Bible, Quar’an, and Torah) that life was literally breathed into the first human by a divine power, is actually (and perhaps unsurprisingly) not confined to the Abrahamic religions. Examples of similar creation myths appear in Ancient Egyptian, Ancient Greek, and Māori belief systems. In fact the hongi, the Māori greeting in which two individuals press their noses together, symbolises the sharing of this breath of life, said to have been originally shared with the first human by the god Tāne.

“Then He proportioned him and breathed into him of His Spirit, and made for you the hearing, the sight, and the hearts.”

– Quar’an 32:9

“Then the Lord God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.”

– Genesis 2:7

“And the Lord God formed man of dust from the ground, and He breathed into his nostrils the soul of life, and man became a living soul.”

– Bereshit 2:7

The breath holds similar importance in eastern faiths. In Buddhism, Hinduism, and Daoism, breathing is not only understood as a vital component for life, but as a focus that can be harnessed for physical growth. Breathing is also central to practices that emerged from Ancient China and India and remain with us today, such as qi gong and yoga respectively. Whilst today yoga is widely misunderstood in the West to be purely a form of exercise (which it certainly can be, and is, in many cases), its original conception was intrinsically linked to what Westerners today may simply call “meditation”, with a focus on the breath, known as “prānāyāma” (प्राणायाम), as a key component.

“Breathing in, one observes impermanence. Breathing out, one observes impermanence.”

— Ānāpānasati Sutta MN 118

I plan to focus here less on the many cultural and religious conceptualisations of the breath and look closer at language, and the way we have tied the importance of breath to our lives through the words we use.

The risk of me chasing tangents on links to belief, faith, culture, and myth are very high (as these things wield huge influence on the words a people use), so forgive me in advance if I stray off the course I’ve charted.

The English Connection

The linguistic relationship between breath and life isn’t readily found in common Modern English parlance.

The word “life” comes to us from the Old English “līf” (with essentially the same meaning) which itself evolved from the Proto-Germanic “lībą” which meant both body and life more generally. It’s argued that “lībą” was derived from another Proto-Germanic word; “lībaną”, meaning to stay, to be left behind, or to remain. It’s tempting to assume the body (lībą) was referred to as such, as it was the part of us that stays or remains after death (indeed, in Modern English we also refer to corpses as “remains”), but I haven’t found any sources to support that, so it’s just a presumption. All of these words are thought to come from a Proto-Indo-European great-grandparent; “leyp-” meaning to stick. It is hypothesised that this root ultimately gave the Modern German language both of the (at first seemingly unrelated) words “leben” to live, and “kleben” to stick.

I’ll be briefer with breath. “Breath” evolved from Old English “brǣþ” which could be used to refer not only to the air that came in and out of our bodies, but also vapours, odours, and scents. This word is believed to come from a Proto-Germanic noun of the same meaning; “brēþiz”, which is thought to be derived from the Proto-Germanic verb “brēaną”, meaning to give off a fume, smell or vapour. There’s some argument to be made that this word has given us both the Modern English words “breath” (the vapour that leaves the mouth and nose) and “broth” (a food from which a vapour rises).

So, we can trace one back to “sticky” and the other back to “vapour”…

It’s safe to say that in Modern English, the words breath and life don’t share much of an obvious relationship at all.

Yet, when we begin to look at synonyms, the picture changes somewhat.

Let’s stop talking about breathing, and talk instead about respiration.

If you’re studying for a Biology GCSE, respiration is the process of producing energy, but if you’re anyone else, it simply means breathing.

To respire is to breathe, and the word comes to us from the Latin “respirare”; the “re-” prefix meaning again (repeat, recall, revisit), and “spirare” meaning breathe.

Keep “spirare” in mind (remember).

It’ll be coming back (returning) later.

Now let’s look at life. Or rather, lets look at what makes us alive.

What’s the difference between a living body and a dead one?

The answer you’ll hear from many of the world’s major religions (and over half the population of the modern world) is that the living body contains some kind of soul, or spirit, and that in the case of the dead body, this soul has departed. This belief isn’t limited to major modern religions, however. It has existed in various forms throughout history, and across a vast breadth of cultures, religions, and belief systems.

Another difference, one we can (surely) all agree on today, is that the living body is breathing, and the dead one is not. It has ceased to breathe. It is an ex-breather. It’s expired and gone to meet it’s maker. It’s easy to see why such a wide variety of cultures and religions developed a sanctified or spiritual relationship to the breath, given that breathing is such an obvious and observable process which appears to be linked uniquely to the living. In this case, it would hardly be surprising if various cultures perceived the breath to be some sort of animating force, or spirit, which dwells within the living and departs upon death. I’d be willing to bet that its for this reason that so many languages contain links between the words we use to describe the act of living, the concept of a soul or spirit, and breathing. I’ll look at some further examples in other languages later.

Let’s finish uncovering this link in English first. Back to life. So this animating force, this thing which lives within the body, has many names in the many different belief systems which purport its existence. The Abrahamic religions use the words “soul”, “nafs” (نَفْس), and “nefesh” (נפש) to refer to the non-physical part of us that exists inside us, granting us various aspects of our emotions or character, and that will also leave the body upon death, where it shall go on to be judged. These religions also use the words “spirit”, “ruh” (الروح),“ruach” (רוח), and “neshamah” (נשמה).

Those last three are of particular interest, as is the word spirit, which we’ll dissect now.

Some readers might already be a step ahead of me here.

We use the word spirit to talk about this animating power, this life force. A “spirited” person is an energetic one; when “spirits” are high, we mean we are happy, excited, eager; when a person passes on, sometimes people feel that their “spirit” remains.

And from where do we get this word? Well, it came in to Middle English from the Old French “espirit” (same meaning), which itself was a descendant of the Latin word “spiritus”, a noun that could be used to refer to the mind, the spirit, ghosts, and also… air, breath, and breathing. The noun is formed from the verb “spiro”, of which “spirare” is the present infinitive form. And here we return.

(As an aside for those not too familiar with linguistics, the present infinitive form is just a conjugation of the verb — simply; a change in the verb used to express a different meaning — think of how the changes between “run”, “running”, and “ran” all express different meanings in English.)

As mentioned earlier, it’s easy to see (or at least guess) why the Latin language (and as we shall see, many others) used such similar words to express life and breath. In a physical, wordly sense, the link between breathing and living is easily discerned, so it’s reasonable that the word used for the thing in us that gives us life (or that is believed to do so), is the same word we use to talk about this vapour flowing in and out of the living body. A vapour, and a life, that some believe was first breathed into us by a divine being.

So, there’s our link in English, the link between breathing and life, or rather, respiration, and the spirit — delivered to us from Latin through “respirare” and “spiritus.”

Once this first link is drawn to our attention, other examples in English abound. Take first expire, a pretty excellent example which means both to breath out in general, but also to breathe one’s last breath. The “ex-” prefix meaning out or away, the Latin word from which it descends (“exspiro”) was used to refer to the out breath. The word is mostly used today to mean to die, or in the case of food, to spoil, but it can also be used to refer to the process of breathing out (although in Modern English “exhale” is predominant). Here we have a word that refers to the breath leaving the body, but also the spirit departing. A fairly strong connection.

Inspire is another fascinating example. The “in-” prefix meaning within, in, or into, the word has two common uses in Modern English. The first is expire’s opposite: literally to breathe in (again, “inhale” is a more popular alternative). The meaning is generally “to fill with an urge, ability, or desire” or “to cause to happen”. In my opinion, inspire has a markedly more interesting history than its opposite. One might be tempted to ask “If “expire” can mean both the breath leaving, and the spirit leaving, why does “inspire” not mean both the breath entering, and the spirit entering?” The answer is: it does. Just not your own spirit.

(Where did inhale and exhale come from though? More on that later.)

Whilst Modern English “inspiration” can have many sources, “inspiration” in times gone by came from a more divine provider. Since the word literally meant to breath into or to breath in, the word was originally used to speak of people who (much like the biblical first man) had been literally animated by the breath of the gods.

“He knew not his Maker, and Him that inspired into him an active soul.”

– Wisdom 15:10

And this usage certainly makes sense. In a world in which all was believed to be the machinations of the divine, it would be reasonable to feel that great ideas, thoughts, and emotions came not into the mind by chance, but were literally planted (or breathed) into our minds by a god. In fact the term “divine inspiration” is still used to refer to the way in which the original scribes, prophets, and writers of great religious texts were led by heavenly forces. Other remnants of this religious connotation still linger in our modern parlance. Think on what it means to “breathe new life” into something.

There’s a few other interesting Modern English words which have ultimately come to us from the Latin root “spiro”. To start with we have aspire, from the Latin “aspiro” alternatively spelt “adspiro”, which we can break down into “ad-” “spiro”; to (or towards) and breath — to breathe towards. Originally meaning to breathe towards, on, or upon, the word evolved to mean first to favour or aid, and then to approach. Later it developed the usage which we Modern English speakers will be familiar with, meaning to have a desire to do or achieve something. Conspire, is another interesting example, coming from roots meaning to breathe with.

Worldly Inspiration

It might take some attentiveness, but I hope to have shown that, with a keen eye, one can spot the links between life and breath in Modern English. We’ve looked too at the link in Latin, in which the the word “spiritus” was used to mean both breath and spirit. But the connection is a good deal more remarkable when one notices just how many languages it exists within. Let’s conclude with a (hopefully) brief look at some of these.

Ancient Greece is a good enough place to start, given its relationship to the Abrahamic religions (especially Christianity), and its influence on Ancient Rome, and by extension, the Latin Language. The Ancient Greeks used the word “pneuma” (πνεῦμα) to refer to both breath and air, but also figuratively to speak about the life, the spirit, and the divine breath of inspiration. The same root gives us the Modern English “pneumatic” which we use to speak about many things that relate to air.

We’ve talked already of “prānāyāma” (प्राणायाम), a meditative focus on breath control which literally means breath extending. Fascinatingly, the prefix “prāṇá” (प्राण) not only means breath, but also energy, strength, the spirit, and the soul. What’s even more intriguing, in my opinion, is that “prāṇá” (प्राण) is thought to descend from the Proto-Indo-European word “h₂enh₁-” meaning, unsurprisingly, to breathe. Why is that so interesting? Because it is believed that this root evolved into both “h₂enh₁mos” and “h₂enh₁-slo-” which themselves evolved into the Latin words “animus” and “anhelus” respectively. The first meaning spirit or soul, and the second meaning out of breath. Its from words related to “anhelus” that Modern English eventually gets “inhale” and “exhale”.

(I did promise we’d come back to “inhale” and “exhale”.)

The Proto-Indo-European word “h₂enh₁-” is also posited to have been the forerunner of a number Parthian, Kurdish and Iranian words that variously related to either the soul or the breath.

(When working with Proto-Indo-European words, its hard to say much with absolute certainty. Regardless, there’s a number of interesting words that are hypothesised to have come from this ultimate root.)

Another link can be found in Classical Chinese, in which the glyph “氣” was used to refer both to breath and also vital energy, or life force.

And for our final full circle, we return to the words used in Arabic and Hebrew to refer to the spirit; “nafs” (نَفْس), and “nefesh” (נפש) respectively. Would you be surprised to learn that both can also be used to refer to the breath? They do. As mentioned, these languages also contain the words “rúakh” (רוח) and “ruh” (روح) which again can be used to refer variously to ghosts, spirits, souls, and breath. These two distant cousins also descend from the same Proto-West Semitic root word (hence their similar sounds).

Why?

Given that these intriguing patterns and connections have emerged in languages around the globe, the curious may be wondering how exactly this came to be, or rather, why?

There’s a few explanations for all these patterns, and I personally believe a combination of two are mostly responsible here:

1) Independent development

2) Shared linguistic ancestors

Independent development

In the first instance, it’s entirely understandable and even predictable that certain cultures would develop a link between breathing and living, and would use similar words when talking about these things, as we have discussed earlier. This certainly helps to explain why such geographically separate cultures exhibit the same linguistic link.

Shared linguistic ancestors

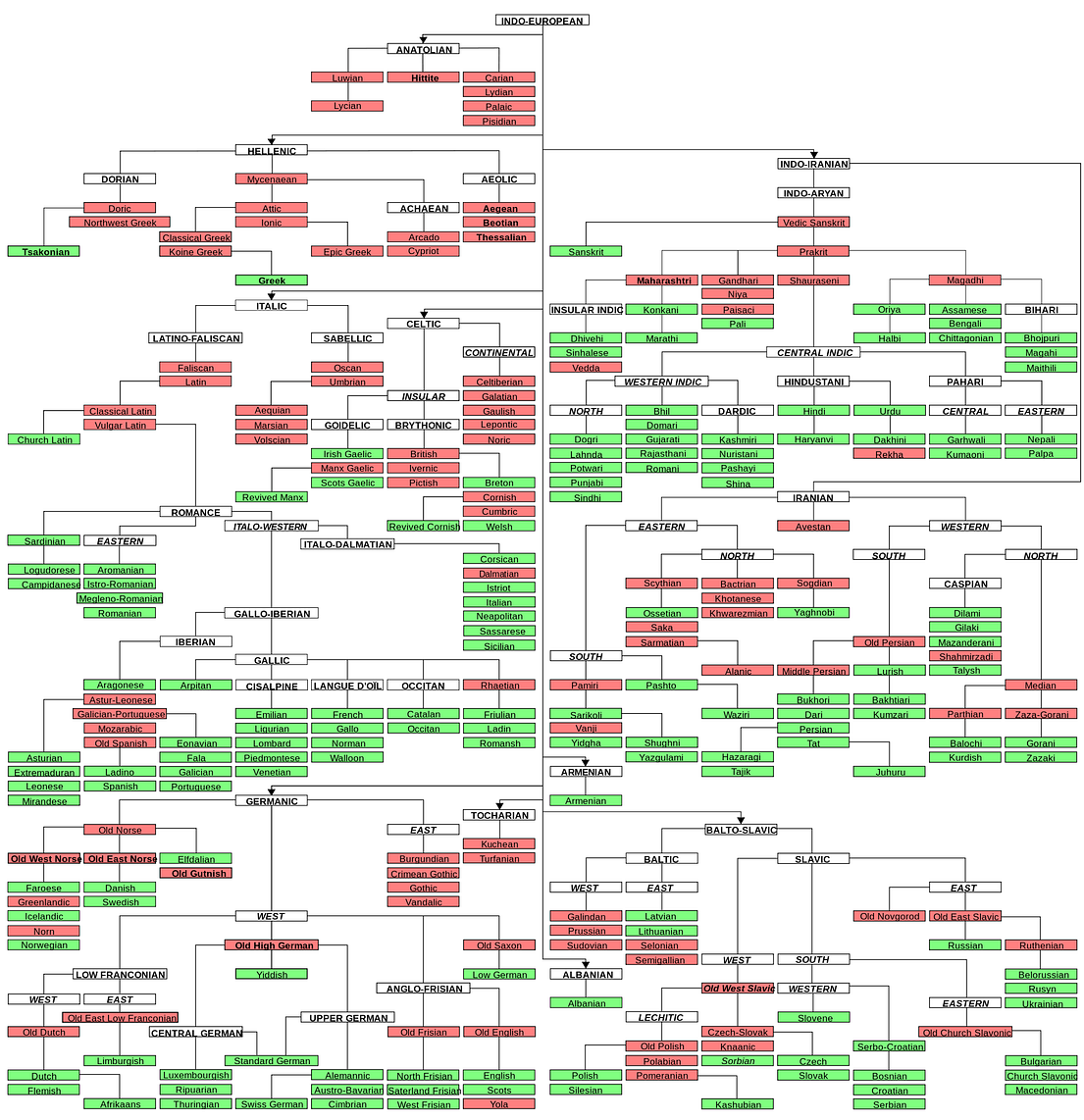

This is something I’ve talked about a lot through the course of this article, but I thought I’d give it another short explanation for anyone unfamiliar with historical linguistics.

For the sake of brevity and simplicity, allow me to make an imperfect explanation.

Imagine languages like a family tree. I’ll use Proto-Indo-European as our example. This is our great-grandparent.

As the Proto-Indo-Europeans, the prehistoric people of Eurasia, travelled across the continent, they split in to groups, and spread to separate corners. These people developed their own languages wherever they ended up, languages that developed from Proto-Indo-European. PIE now has a number of children.

Two of these children are Proto-Germanic and Proto-Italic. The grandparents of our family tree.

They have their own children (and again, I’m simplifying greatly here).

Proto-Germanic has children; Old Norse, Old High German, Old English, to name a few. Proto-Italic has children too, among them; Latin.

These various languages then have their own children; Danish, Norwegian, German, English on the one side, Italian, Spanish, French on the other.

Because they share a common ancestor, many of their words are cognates — words that also share an ancestor (and thus often sound or look similar).

And just like in a real family, you likely look quite similar to your siblings and your parents, but less so to your cousins, even though the link is there. Similarly, you and all your cousins probably look just a little bit like your grandparents, even though the resemblance might be hard to spot at first glance.

To demonstrate, I present the Proto-Indo-European word “méH₂tēr-”. This ancestor gives our languages from above, in the order they were listed: Mor, Mor, Mutter, Mother, and Madre, Madre, Mère.

Additionally, in the case of the languages closely associated with the Abrahamic faiths (and I suppose some others), loaning and translating could also have played a part. When religious texts were shared and rendered into new languages, connections between certain words (like those used for the soul or for breath) were potentially carried over into the target language. This could help explain why similar patterns are found across Greek, Latin, Arabic and Hebrew.

Expiration

We benefit from our breath every day, rarely thinking much of it. The same goes for words, which we mostly employ without ever a second thought as to where they might have come from, or why we might be using them the way we do.

It can be a challenge to conceptualise the way people thought and felt millennia ago, but the words these bygone people used, which thus birthed the descendant words that we use today, provide at least something of a small aperture into the past. And whilst the image we garner from this glimpse might be hazy, it can still inspire, and breath new life into our own ways of thinking.

There ends my exploration of the linguistic tether that fastens life to breath. I hope you found it as interesting to read as I did to research.

Clarifications

I’d like to make two clarifications.

The first is that all the Proto-languages I have been talking about in this article are what linguists call “reconstructed languages,” which means they are hypothetical.

This doesn’t mean they didn’t exist — in fact most scholars agree that they certainly did, and generally the details of these languages are also broadly agreed upon. But, these languages are unattested (meaning we have no written record of them), so they are reconstructed by comparing features from descendant languages. The Wikipedia article on linguistic reconstruction is fairly concise, if you’re interested.

Second, I’d like to point out that I’m no expert on history, linguistics, nor the cultures of the world — ancient or modern. I’m merely someone with an interest in the topics. If I’ve made any errors, mistakes, or omissions, I’d be happy to hear any feedback. Let me know — and thanks for reading!

I hope you’ve been inspired.

Leave a comment