This essay was originally published on Medium on September 26th 2022.

The serpent is a creature that suffers from a somewhat imperfect, volatile PR strategy. Throughout our history the animal has populated our lands, thoughts and tales, a denizen of the cosmic realm as often as the earthly. As best said by Okuda & Kiyokawa; “no animal has been more worshipped yet more cast out, more loved yet more despised than the snake.”

Whatever great deed or crime the world’s first serpents committed, or whatever instinct is buried within the human mind that elicits such imaginative, intense responses to their presence, they have become so tightly coiled around our history that it is impossible to avoid them. As far back as the Sumerians the snake has represented vitality, healing and life, a role it enjoys to this day, still comfortably constricting the Rod of Asclepius on almost every ambulance on earth. Yet the very same creature is accused of swindling the human race out of paradise in the Bible, Torah and Qu’ran alike (although some Gnostics venerate this scriptural snake as a guide toward holy secrets forbidden), the great serpent Níðhöggr is said to eat at the very roots of the tree of life itself in the Poetic Edda, they turn heroes to stone when found atop the heads of the Gorgons, and likely gave birth also to every wyrm, wyvern, dragon and drake that have appeared in myths of the past and the fantasy of today.

Yet none of these manifestations of the snake are quite so intriguing, and so misunderstood, as Ouroboros, the tail eater, the serpent that devours itself. Gracing the pages of texts hailing from as far back as the reign of Tutankhamun, this auto-cannibal has appeared in almost as many varied beliefs as its not so hungry brother, although perhaps in less varied roles. It is a creature of magic and of disorder, an endless consumer and creator. In some beliefs malevolent, others benevolent, in some it is small enough to hold in the hand, in others it is so large that it encompasses the entire world. And although you’d be hard pressed to find many that would still insist that the the world is so surrounded by a serpent, those who feel that their world is plagued by some sinister constriction are not so rare.

What are we to do then, when we find ourselves encircled by such a powerful, venomous, and eternal creature?

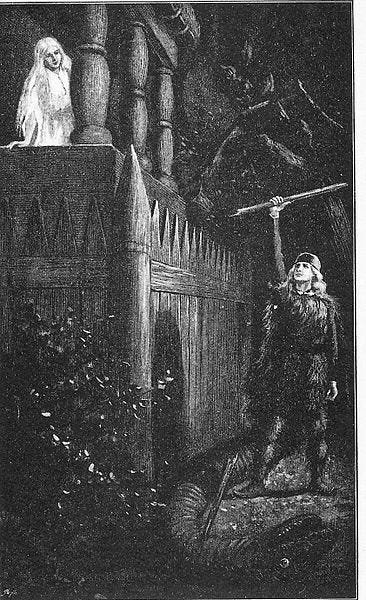

If we return to Norse legend, we find in one of the many tales of Ragnar Lodbrok a serpent that encircles the bedroom of the princess Thora, trapping her within. How strange it is that so many of us today can find shared experience with Thora, despite the years and miles that separate us, confined as we often feel by forces out of our control. Entrapment within our bedrooms may for many of us now be but a nearly forgotten feature of a fading pandemic, but to feel constricted by a great, world-encircling presence is proving to be an enduring experience.

This macro level encirclement of our lives by political, economic and social serpents can often reduce us, on the micro level, to the position of poor Thora, held within an ever tightening grip, perhaps even literally also unable to leave our own rooms.

Yet unlike Thora, we cannot wait for Ragnar Lodbrok to slice the beast in two and free us. As we navigate our lives constricted, feeling as if some great snake is squeezing the breath from our lungs and filling our veins with its venom, it is often challenging to notice our own transformation into Ouroboros, running in circles, devouring ourselves.

Anxiety, helplessness, fear. These sensations are sadly not auto-cannibalistic, but rather self-propagating, prone to feeding themselves until they grow from being mildly irritating yet pernicious grass snakes to colossal, seemingly world-consuming leviathans. For sadly, one worry compounds another, and the more we find ourselves, like Thora, unable to escape, the increasingly more challenging it can be to try. At each obstacle we chastise ourselves for not performing more effectively, consuming ourselves further, reducing what confidence remains. It is a cycle that can be as dangerous and eternal as the Ouroboros itself.

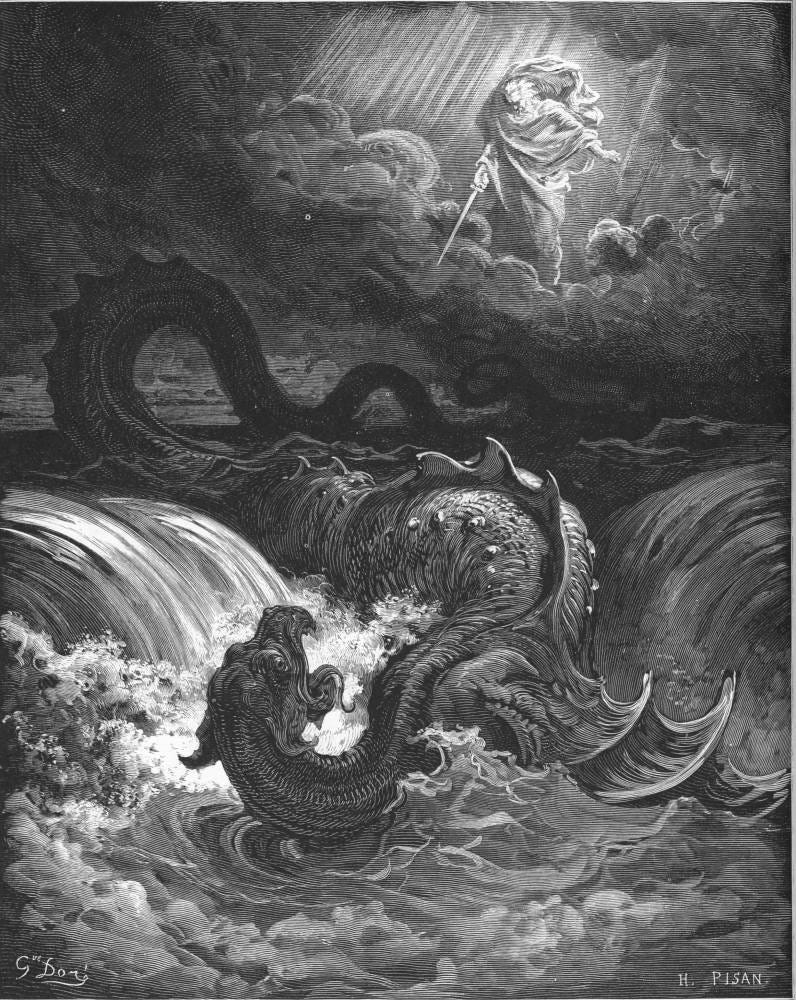

How can we proceed? What can we do to escape this cycle? How might we slay the snake that devours itself? In both the Tanakh and the Bible, it is said that the great sea serpent, the Leviathan, shall eventually be slain, and this shall usher in a new era of peace, and a world free of all evil. Rejoice! Unfortunately, we are told that this great deed shall be performed on the very last day, at the end of time. For most of us, this is a little too long to wait.

Perhaps we can find a clue in the heroics of Li Chi, a young girl from 4th century Fujian, China, who is said to have slain a giant cave-dwelling serpent, in the appropriately named Li Chi slays the Serpent. So how does she go about the task? In this tale, the great snake is first lured from its lair by the scent of rice cakes, before being set upon by a snake-hunting dog, and ultimately chased down by Li Chi and dispatched by sword. Here lies some instrumental insight on the extermination of our snakes:

– The importance of a distraction.

– The benefit of a companion.

– The prestige of bravery.

Li Chi is not alone in the application of these techniques. Beowulf could not have defeated his wyrm were it not for the aid of Wiglaf, Polish prince Krakus employed distraction to smite Smok Wawelski, and Tolkien’s Túrin Turambar too called upon an (albeit ill-fated) companion to complete his charge. Certainly, one could point out that these are all but tales and legend, and provide little aid in the practical act of slaying the serpents that fetter our own minds and lives. But perhaps if we employ the first of our identified techniques; distraction, we may find that our beasts are no less illusory. But of course, logic is sometimes ironically unsuccessful in dispatching the illogical. Simply knowing that we should direct our attention away from that which besets us seldom means that we can. That which exists only technically within our minds can, to the dismay of many, still prove to be a very real obstacle.

As we drift now in to the realm of psychology, our methods might be best introduced by Carl Jung’s thoughts on the great self-devourer.

“It is said of the Ouroboros that he slays himself and brings himself to life.” — Collected Works, Vol. 14

What can we learn from the overcoming of mythical beasts, that will allow us to overcome a very real beast, the most pernicious of myths that we devour ourselves with; those limiting beliefs, anxiety, and lack of self-worth with which we so often judge ourselves far more harshly than we do our peers? How can we liberate ourselves from doubt and auto-cannibalism, slaying that which impedes us, and finally, bringing ourselves to life?

Whilst distraction may be the secret sorcery that dispels the monster to mist, it is often hard to merely shake our snakes off from us, the Ouroboros is after all, without end. And whilst facing our fears alongside companions can bring us the courage needed to succeed, not all of us possess dogs trained to hunt snakes, and even Beowulf was abandoned by all his allies beside one. Certainly, if we are fortunate enough to be blessed with comrades with whom we can valiantly stride within the dark cave, then we may find that for a while, our serpents can be driven away. However, we all know too well that even with the gift of friends by our sides who will carry our banners, it is sadly, sometimes not enough. We must then rely upon ourselves. We must rely upon our own bravery.

How did Li Chi feel as she entered that cave? The tale does not reveal to us what she was thinking, if she felt afraid, how she reckoned her chances of success. Confidence, much like the Ouroboros, can be imagined as a cycle. As aforementioned, the more we avoid challenges, the less capable we feel of tackling them as they arise in future. Yet by this same token, the inverse is true also. To become brave we must be brave. We limit ourselves, trap ourselves, devour ourselves, by believing that we are not brave enough yet to tackle our serpents, that we cannot act courageously for we have not the confidence. But resolve is a plant that propagates itself, a creature that brings itself to life. As we look for small examples of our own courage in our past endeavours, we shall see that even though we feel too powerless to face our trials, our history proves otherwise. Once we learn that we do not need to feel brave to act as such, the cycle continues with each courageous act, no matter their size. Simply because our serpents are a challenge to slay, does not mean it cannot be done.

To be graced with this dauntlessness now, immediately, would of course be a welcome gift. But life cannot be so. It is the leaps we take when we feel most afraid for which we feel most elated upon our landing. And we always land, perhaps scathed, perhaps shaken, but land we do nonetheless. If we can distract ourselves, excellent. If we can enter the cave beside a friend, ideal. But if we cannot? We must remember that fortune favours the bold, and boldness begets boldness. We do not need to feel bold to act boldly. We need but hope, and faith in ourselves.

The snake is much more than a creature that slithers through the shadows with venom on its teeth and cunning in its eye. The snake is a bold guardian of its home, and a creature able to shed its restrictive flesh to be birthed anew. We too can shed that which binds us, to cease living only as the Ouroboros that slays himself, and rather transform in to the Ouroboros that brings himself to life. With each success we learn of our own ability, and with time, we find ourselves liberated from the serpents that once constricted us. In the Pali Canon it is said that whilst the Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree, he was assailed by seven days of torrential rains, unending cloud, and biting cold. It was then that the King of the serpents, Mucalinda, arose from the soil, coiling around the Buddha and protecting him with his hood. As the sky became clear, the snake King retired, and the Buddha spoke thusly;

There is happiness for he who is free from ill-will in the world.

There is happiness also for us who brave the storm. With time and practice we can find ourselves shielded from the tempest by the very beliefs that once held us captive.

Leave a comment