This essay was originally published on Medium on January 26th 2024.

This article is based upon a university essay I wrote in October 2023 entitled “How useful are contemporary English chronicles for helping us to understand the revolt of Owain Glyn Dwr? An analysis of two primary sources.”

I’ve edited it as best I can to improve its readability and accessibility, whilst still aiming to change as little as possible. I’ve also added a brief introduction and images that were not present in the original. Errors, including the formatting and referencing errors, have been maintained.

At the dawn of World War 1, the Welsh were called to arms by a headline in the Llangollen Advertiser reading; ‘SONS OF GLYNDWR, AWAKE.’ Whilst the medieval soldier remained (and still remains) a national figure in Wales centuries after his death, he is not nearly as well recalled to the east of Offa’s Dyke, in England.

For a long time Owain Glyndwr has been depicted by historians as a leader of a great national revolt, a freedom fighter, the last native prince of Wales, a man who stirred his people to rise against their English colonisers. Recent scrutiny of the contemporary evidence by Gideon Brough (whose book on the topic I would highly recommend) has suggested, however, that this image may be overly simplistic. Yet whilst Glyndwr may or may not have been ‘responsible’ for the rebellions that first flared across Wales between 1399 and 1401, he certainly played a significant and sometimes central role, one for which he has been firmly fixed within history.

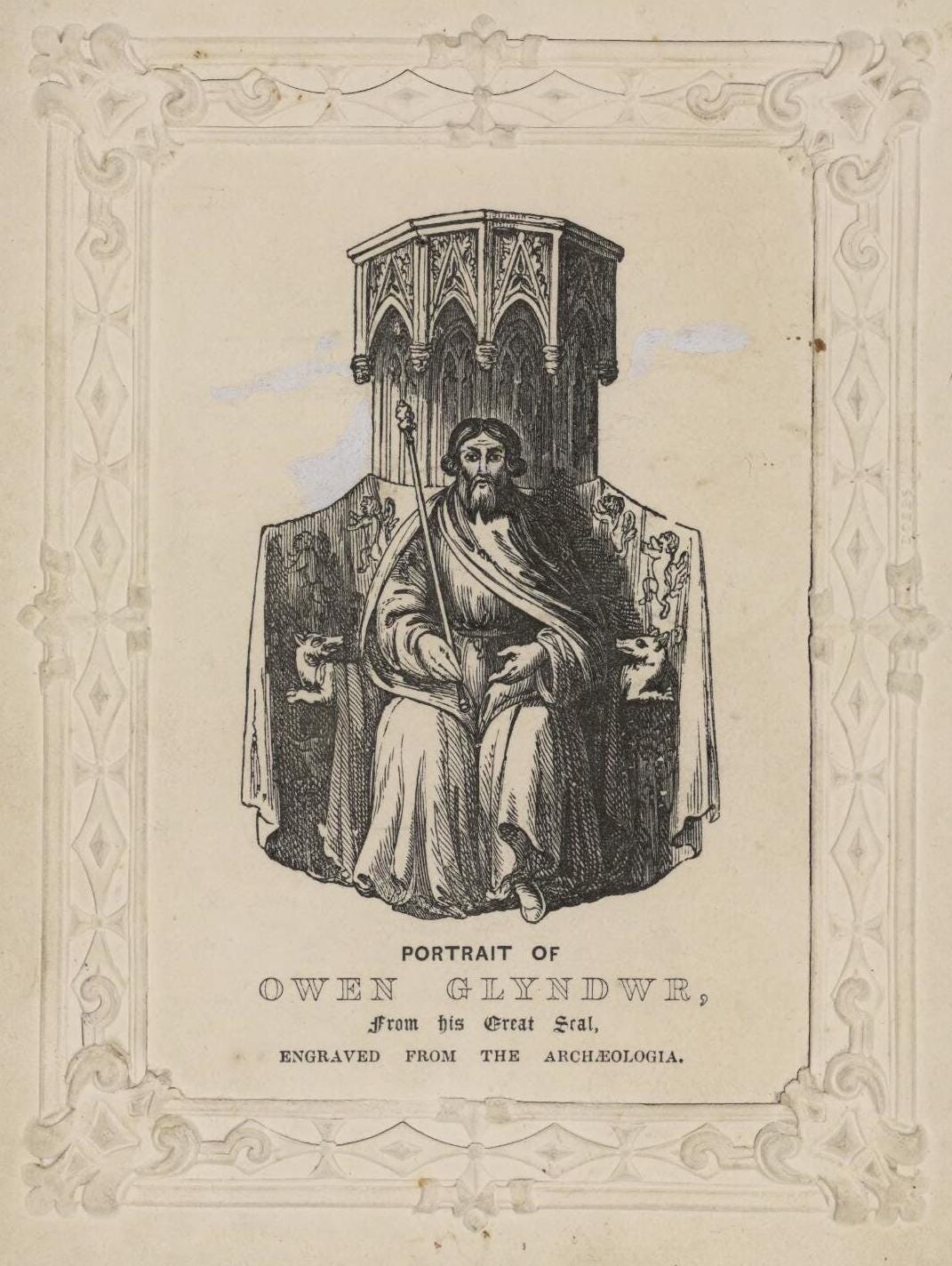

It seems we can, however, say some things with a degree of certainty. Owain was born in Wales around 1355, a time in which hopes for Welsh independent rule seemed all but extinguished. He was born to a noble family and could trace his lineage back to a number of the royal dynasties that had controlled regions of Wales before the English conquest of Edward I in 1284. Owain was a landowner and soldier, and had even fought for the English crown on several occasions. However, whatever loyalty he had felt towards England, if he had ever felt any at all, had clearly diminished by 1400, when he rose in revolt against Henry IV.

Whatever his motivations and whatever the inciting incident, it is clear from the record that Owain fought for nearly fifteen years against English rule, and succeeded in gathering support, both at home and abroad, for a Welsh nation freed from the English yoke.

Glyndwr’s revolt erupted in a time of famine, pestilence and poverty in Wales, a time of turmoil in England, and a time of insurrection across Europe.¹ Whilst modern scholarship disagrees on Owain’s role as the head of a national rebellion, it’s clear that some contemporary sources wished to paint him as such.² English chronicles such as the Dieulacres and that of Adam Usk provide valuable insight into the rebellion, but remain heavily influenced by their authors’ own backgrounds and predilections. In their detailing of the revolt, the chroniclers unwittingly hint at aspects of Owain they seem to have wished to obscure, illuminating their own biases in the process. They provide distorted records of Glyndwr’s life, but useful records nonetheless.

The Dieulacres Chronicle, composed in the Cistercian Abbey of Dieulacres, Staffordshire, includes an annalistic history of England from 1337 to 1403, composed by two different authors.⁴ Whilst the chronicle’s outset is mostly a transcription of other works, in 1399, the first author began to describe events he knew first hand.⁵ His work was continued in 1400 by a second writer, a staunch supporter of Henry IV.⁶ Writing through a period of transformation and instability, both writers were influenced by vested (and sometimes opposing) interests.⁷ ⁸ The second writer worked during the reign of a divisive usurper who faced conflict with Scotland, Ireland, France and Wales, as well as threats from within.⁹ The chronicle preserves the events of the Glyndwr revolt between 1400 and 1402 for posterity, describing how an “evil-doer… setting himself up as the Prince of Wales… plundered” English townships in Wales.¹⁰ With repeated references to the treachery of the Welshmen under Owain, the chronicle records various notable incidents of his rebellion. We are told of the capture of Reginald Grey, a powerful English baron whose family had been settled in the Marches of Wales in order to restrain the natives. The chronicle records the seizure of Conwy castle, one of the most imposing defences in north Wales. We also hear of the capture of another formidable English nobleman, Edmund Mortimer, along with his subsequent conversion to Owain’s cause and marriage to the Welsh soldier’s daughter.¹¹

Of whether the author of the chronicle possessed a bias in favour of king Henry there can be little question. Not only was the king the patron of Dieulacres, there’s a likelihood the chronicler knew him personally.¹² As such, we can imagine how the writer’s motivation to besmirch the king’s adversary, denouncing Glyndwr as a deceitful plunderer and a threat to the powerful of England and the Marches.

Adam Usk, a lawyer native to Wales, compiled his chronicle between 1401 and 1421. Despite his Welsh ancestry, Adam was well entrenched within the learned and noble circles of England, and we can certainly refer to his chronicle as an ‘English’ one. In 1401, Usk was working at the court of archbishop Arundel and regularly served as counsellor to Henry IV.¹³ Given-Wilson argues that Usk, having witnessed and played a role in Henry’s turbulent ascension, was likely conscious of his proximity to a remarkably significant period.¹⁴ The expectation of witnessing, and possibly influencing, further significant events likely motivated him to begin his chronicle.¹⁵ Usk began recording Glyndwr’s revolt contemporaneously, at the apogee of his own career.¹⁶ However, his record from 1402 onward was maintained outside of England, during which time Usk fell from Henry’s favour.¹⁷ His records of this period were committed to the chronicle in 1414, after receiving the king’s pardon and returning to England in 1411.¹⁸ Usk tracks Glyndwr’s revolt from his first “plundering” of North Wales to the ultimate capture of his wife and daughters in 1409, after which Owain “in his misery hid himself away… in caves and…mountainsides.”¹⁹ Whilst Usk occasionally trains a critical eye on the behaviour of the English combatants, lamenting particularly their destruction of Strata Florida Abbey, and the execution of Welshmen at the king’s command, the picture Usk paints is still far from balanced.²⁰ Usk alludes to Glyndwr as a coward and a deceiver, a man who hides among caves and forests, a leader of “wretches” engaged in pillaging, slaughtering and “carrying away riches to the mountains,” wretches who too did not “spare even the churches”.²¹ Usk’s characterisation of Owain’s troops as cave-dwelling “manikins” was very likely influenced by, and perhaps pandered to, pejorative perceptions of the Welsh as primitive barbarians.²² ²³ ²⁴ Such anti-Welsh sentiment often flared in times of crisis.²⁵ There is a great deal to be considered about the ways in which Usk used such stereotypes to tarnish the name of a fellow Welshman, in order to better his own standing and perhaps even present himself as a Welshman unlike those ‘others’ — a loyal, civilised, educated, and perhaps model minority, but this is unfortunately beyond the scope of this essay.

Taken together, these sources reveal a great deal about Glyndwr’s revolt. Both record many of the key events, albeit selectively. They describe Owain’s guerrilla tactics, for instance, but explain them as marks of savagery and treachery, whilst concealing the English ignorance of the areas in which they fought, and their struggle to counter a highly mobile enemy.²⁶ Whilst English chroniclers designated these stratagems as brutishness, Welsh poets were praising the wilderness for the advantages it accorded them.²⁷ Both sources hint at Glyndwr’s cognisance of diplomacy, and thus unwittingly contradict the aforementioned allusions to his savagery.²⁸ Both frame the marriage of Edmund Mortimer to Owain’s daughter as an act of treachery on Glyndwr’s part and error on Mortimer’s, but neither acknowledge Owain’s diplomatic prudence, nor the English government’s disastrous oversight in failing to pay Mortimer’s ransom and secure him a timely release.²⁹ Usk describes the parliaments held by Owain as the mimicries of a usurper, but in doing so intimates Glyndwr’s growing political ambition and aspiration.³⁰ ³¹ Further such examples in the chronicle include Owain’s attempts to summon international support.³² In his letter to the Scottish king, reproduced by Usk, Owain invoked shared Celtic ancestry and mutual enmity toward the “Sacsouns”, hinting perhaps at Glyndwr’s appreciation of the power of such invocations, if not his own worldview.³³ ³⁴ The misrepresentations become particularly pertinent when they shape modern discussion and lead to divergence of belief among scholars. Both chronicles assert that Glyndwr had been proclaimed prince in 1400, a claim historians John and Robert Davies accept, but one rejected by Brough, who argues that it only appears in “a few biased… sources of debatable reliability” which “intended to denounce Glyndwr”.³⁵ ³⁶ ³⁷ It’s notable that a comparable Welsh chronicle of the revolt not once references Owain claiming the title of “prince”.³⁸

The authors’ backgrounds clearly colour their writings. In Dieulacres, the author makes clear he is imparting his own “objective” view of history. Beginning in 1400, continuing the work of the prior author, he writes “this [previous] commentator has in places condemned the commendable, and commended the condemnable,” and “I have been… in many places… and therefore I know the truth.”³⁹ And whilst Usk’s allegiances are not always as clear, his feelings are often plain.⁴⁰ His “heart trembles” when Reginald Grey is captured, and it “grieves him to relate,” Edmund Mortimer’s fate.⁴¹ Mortimer’s father was Usk’s first patron, and funded his studies at Oxford.⁴² Much of Usk’s writing on Owain was added to his chronicle at a time he was trying to rebuild his damaged reputation.⁴³ Crucially, during his time on the continent, Usk was found to be communicating with Glyndwr’s allies, which Henry suspected as collusion.⁴⁴ Usk’s writings critical of Owain and his reliance on common stereotypes of Welsh barbarity, could be considered attempts to clear his own name, distance himself from his countrymen, and return to the establishment’s good graces, although it’s not clear exactly who his intended audience was.⁴⁵ ⁴⁶ Yet where these sources omit or misrepresent certain information, other primary sources provide partial aid. Walsingham’s Historia Anglicana, for instance, references the rivalry between Reginald Grey and Owain, now understood as one of Owain’s incentives for revolt.⁴⁷ ⁴⁸

The biases and backgrounds of the chronicles’ authors must be carefully considered in order to form a clearer understanding of Owain Glyndwr. Whilst they appear to present the salient events of the revolt, these sources must be treated critically. Historians must remain mindful that parts of these reports may have been crafted to denounce the man they documented.⁴⁹ However, John Taylor reminds that attempts of medieval chroniclers to present their own narrative were not uncommon, and remain valuable in their demonstration of contemporary thought and the chronicler’s own outlook.⁵⁰ In this case, not only can the chronicles suggest much about Owain’s actions and objectives, they also illuminate their authors’ views, biases and intentions. They provide vital insight into the English response to Glyndwr, and the influences that informed this response.

Further Reading:

- Adam of Usk, The Chronicle of Adam Usk, ed. and trans. by Chris Given-Wilson (Oxford, 1997)

- Brough, Gideon, The Rise and Fall of Owain Glyn Dŵr: England, France and the Welsh Rebellion in the Late Middle Ages (London, 2017)

- Fisher, Michael, Dieulacres Abbey (Leek, 1969) — Accessible online here

- Given-Wilson, Chris, Chronicles: The Writing of History in Medieval England (London, 2007)

- Ruggier, Jennifer, Welsh Identity and Adam Usk’s Chronicle (1377–1421), (unpublished doctoral thesis, Wolfson College, Cambridge, 2021) — Accessible online here

- John Davies, A History of Wales (London, 1993), p196; Geraint H. Jenkins, A Concise History of Wales (Cambridge, 2007), p. 102.

- Gideon Brough, The Rise and Fall of Owain Glyn Dŵr: England, France and the Welsh Rebellion in the Late Middle Ages (London, 2017), Chapter 1, para. 1–2; Robert R. Davies, The Revolt of Owain Glyn Dŵr, (Oxford, 1995), Chapter 4, para. 1; Davies, History, pp. 194–200; Jenkins, Concise History, p.112.

- Adam of Usk, The Chronicle of Adam Usk, ed. and trans. by Chris Given-Wilson (Oxford, 1997), pp. 100, 134; Anon., Dieulacres Chronicle in Alicia Marchant, The Revolt of Owain Glyndwr in Medieval English Chronicles (York, 2014), pp. 237–240; Thomas Walsingham, Historia Anglicana, II, 246, Passage 1a. in Marchant, Chronicles, p. 219; Polydore Vergil, Historia Anglica, p. 434, Passage 7c. in Marchant, Chronicles, pp. 242–3.

- Chris Given-Wilson, Chronicles of the Revolution, 1397–1400, The Reign of Richard II (Manchester, 1993), p.9; G. C. Baugh and others, ‘Houses of Cistercian monks: The abbey of Dieulacres’, in A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 3, ed. M. W. Greenslade and R. B. Pugh (London, 1970), pp. 230–235; Edward D. Kennedy, ‘Dieulacres chronicle 1337–1403’, in: Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle Online, ed. by Graeme Dunphy and Cristian Bratu (2016). Available at: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopedia-of-the-medieval-chronicle/dieulacres-chron icle-1337–1403-SIM_00887, Accessed 27 November 2023.

- Maude V. Clarke and Vivian H. Galbraith, ‘The Deposition of Richard II’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 14.1(1930), pp. 131–132

- Michael Fisher, Dieulacres Abbey (Leek, 1969), Chapter 9, para. 13; Clarke and Galbraith, ‘The Deposition’, p. 128.

- Anthony Goodman ‘Introduction’, in Henry IV: The Establishment of the Regime, 1399–1406, ed. By Gwilym Dodd and Douglas Biggs (Suffolk, 2003), pp.1, 9

- Clarke and Galbraith, ‘The Deposition’, p. 128.

- Joel Burden ‘How Do You Bury a Deposed King? The Funeral of Richard II and the Establishment of Lancastrian Royal Authority in 1400’, in Henry IV: The Establishment of the Regime, 1399-1406, ed. By Gwilym Dodd and Douglas Biggs (Suffolk, 2003), p. 40; Brough, Owain Glyn Dŵr, Chapter 1, para. 1, Chapter 2, para. 3

- Anon., Dieulacres, p. 237.

- Ibid., pp. 237-239.

- Clarke and Galbraith, ‘The Deposition’, p. 133.

- Chris Given-Wilson, ‘Usk, Adam (c. 1350-1430), chronicler’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford, 2008). Available at: https://www-oxforddnb-com.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.000 1/odnb-9780198614128-e-98/version/1, Accessed 27 November 2023.

- Chris Given-Wilson, ‘The Dating and Structure of the Chronicle of Adam Usk’, Welsh History Review, 17. 4 (1995), pp. 522, 525.

- Ibid., p. 525.

- Given-Wilson, ‘Usk, Adam’, in ODNB.

- Given-Wilson, ‘Dating and Structure’, pp.527-9; Given-Wilson, ‘Usk, Adam’, in ODNB.

- Given-Wilson, ‘Dating and Structure’, p.527.

- Usk, The Chronicle of Adam Usk, pp. 100, 243.

- Ibid. p.144.

- Ibid. pp. 100, 134, 144, 146, 158, 162.

- The pejorative sense is clearer in Usk’s original “homunculis” than Given-Wilson’s translation to “manikins”.

- Usk, The Chronicle of Adam Usk, p.173.

- Rees Davies ‘Buchedd a Moes y Cymry’ [The Manners and Morals of the Welsh], Welsh History Review, 12 (1985a), pp.174–179.

- Matthew F. Stevens and Teresa Phipps, ‘Towards a Characterization of Race Law in Medieval Wales’, The Journal of Legal History, 41.3 (2020), p.291.

- Jennifer Ruggier, ‘Welsh Identity and Adam Usk’s Chronicle (1377–1421)’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Wolfson College, Cambridge, 2021) p128.

- Llywelyn ab y Moel, I Goed y Graig Lwyd, trans. by John K. Bollard in Owain Glyndŵr: a casebook (Liverpool, 2013), pp. 132–133.

- Davies, Revolt, Chapter 4, para. 11.

- Davies, Revolt, Chapter 6, para. 19–23; John E. Lloyd, Owen Glendower (Oxford, 1931), pp. 82–84, 101, 119.

- Usk, The Chronicle of Adam Usk, p.177.

- Ibid., p.146.

- Ibid.

- Brough, Owain Glyn Dŵr, Chapter 2, para. 18, Chapter 10, para. 2.

- Anon., Dieulacres, p. 237; Usk, The Chronicle of Adam Usk, p.100.

- Davies, Revolt, Chapter 4, para. 1; Davies, History, pp. 196.

- Brough, Owain Glyn Dŵr, Chapter 1, Section 2, para. 6–8.

- Anon., Annals of Owen Glendower in John E. Lloyd, Owen Glendower (Oxford, 1931). Available at https://www.deremilitari.org/RESOURCES/SOURCES/owainglyndwr.htm, Accessed 27 November 2023.

- “Iste commentator in locis quampluribus vituperat commendanda et commendat vituperanda” and “in multis locis interfui et vidi et propterea veritatem novi.” Translation mine. Clarke and Galbraith, ‘The Deposition’, p. 133.

- Chris Given-Wilson, ‘Introduction’ in The Chronicle of Adam Usk, (Oxford, 1997), pp. xxx-xxxi.

- Usk, The Chronicle of Adam Usk, p.158.

- Given-Wilson, ‘Usk, Adam’, in ODNB.

- John E. Lloyd, ‘ADAM OF USK (1352? — 1430) in contemporary notices ‘Adam Usk,’ lawyer’, in Dictionary of Welsh Biography, (1959). Available at: https://biography.wales/article/s-ADAM-OFU-1352, Accessed 27 November 2023.

- Usk, The Chronicle of Adam Usk, pp. 212–216 ; Ruggier, ‘Adam Usk’s Chronicle p. 173.

- Davies, Revolt, Chapter 6, para. 19–20

- Ruggier, ‘Adam Usk’s Chronicle p. 22; Given-Wilson, ‘Introduction’, p. lxxxiv.

- Walsingham, Historia, Passage 1a. in Marchant, Chronicles, p. 219

- Brough, Owain Glyn Dŵr, Chapter 3, para. 2.

- Brough, Owain Glyn Dŵr, Chapter 1, Section 2, para. 6–8.

- John Taylor, The Use of Medieval Chronicles (London, 1965), pp. 4–5, 16.

Leave a comment