This essay was originally published on Medium on February 18th 2023.

Note (26th January 2024):

Since writing this article, my personal standards for historical essays have changed slightly.

Firstly, my intention when writing this article was to create something entertaining, and therefore the language I used was quite emotive and maybe not as impartial as it should have been.

Secondly, at the time of writing, I was not taking references and citations particularly seriously on this blog. In the future, if I find the time, I’d like to come back and add citations where appropriate. For now though, I hope the bibliography added below will suffice.

We likely won’t ever know exactly how Constance, Duchess of Brittany felt about her husband, Geoffrey II, but we can speculate. In 1166, Constance’s father, the Duke of Brittany, was in trouble. Across his duchy, powerful nobles were rising up in revolt against him. Desperate, he turned to Henry Plantagenet, King of England and ruler of the Angevin Empire, which at its zenith stretched from the forests of Northumberland to the vineyards of Bordeaux. Henry responded. He rode his troops into Brittany and crushed the revolt. But his support came at a price; the Duke would need to abdicate, leaving the valuable duchy of Brittany to his daughter, Constance. Henry’s master-stroke was to then have the five year old Constance betrothed to his own son, Geoffrey II, who was at the time only a boy of eight. Thus, in one fell swoop, Brittany was firmly under the control of the Plantagenets, even if technically it was currently in the hands of a Plantagenet toddler and his infant wife to be.

Constance spent the majority of her youth in the English court, and eventually married Geoffrey when she reached fifteen. So how might she have felt? Her husband was the king’s fourth son. She would have known the chances of her husband ever ascending the throne himself were almost nil, but they certainly could have enjoyed a life of luxury, reigning over Brittany together. Geoffrey’s chances of inheriting the crown, if there ever were any, certainly plummeted after fighting a losing war against his father — twice. Of his personal life our evidence is limited, but we know he spent a great deal of time with Philip II, the prince of France, and that he was once described by Gerald of Wales, a royal clerk, as being a “hypocrite in everything, a deceiver and a dissembler”, with the ability to “dissolve the firmest alliances and… corrupt two kingdoms.” How then, might Constance have felt when her husband died, aged just twenty-seven, leaving her pregnant with a son who would never know his father? One account tells us that Geoffrey perished in a jousting tournament, crushed to death under the hooves of a horse. Constance was twenty-six when she gave birth to her son, who she named Arthur.

Whatever Constance thought of her first husband, we can be more confident how she felt about the second. Not a year after Geoffrey died, Constance was forced by King Henry to remarry, and he chose as her partner Ranulf de Blondeville. Ranulf had been a knight of the king since he was eighteen, and was fiercely loyal to Henry and the Plantagenet line, which could well explain why he was gifted Brittany. Certainly Constance (who was ten years younger than her new husband), along with the citizens of the duchy, were not thrilled to meet their new duke. Not only did his wife exclude him from the duchy’s government, but the people never acknowledged him as their liege, either. Ranulf’s “control” of the duchy was effectively kept rather more official than actual.

Just a year later, Henry II, the king of England, was dead. The great Angevin Empire passed on to his oldest surviving son, Richard the Lionheart. Richard was a king who needs little introduction. He was known in his time as a great and pious warrior, famed for eventually leading the Third Crusade against the masterful Saladin. We are told he was an elegant man who stood at a good six feet (towering over his younger brothers John and Geoffrey), that his face was cropped with a thick red beard, and that he possessed limbs built for wielding a sword. Yet for all the victories Richard provided in Christendom’s bloody war for the holy land, he failed to provide his realm with a son (at least, not by his wife, which in the domain of mediaeval succession, was all that really mattered).

So in 1190, whilst on his campaign in the holy land, the Lionheart did something quite interesting. Instead of declaring his younger brother, John, as his heir, he chose instead his nephew; Arthur of Brittany. Despite the fact this decision conflicted with the commonly accepted rules of royal succession, no doubt those that knew the king’s younger brother would have breathed a sigh of relief. John was infamous for his poor conduct, cruelty, and “superhuman wickedness.” Throughout his life he would develop a reputation for starving his enemies to death in grisly cells — on occasions, even his former friends received such punishment for their supposed transgressions. Arthur, on the other hand, represented the hope of something different. No doubt Richard knew full well what a ghastly king his brother John would make, and perhaps this is why he opted instead to pass his kingdom to his young nephew. At the time of the decision, the Lionheart was thirty-two, and he had almost a decade left upon the throne. Arthur was but three years old.

Two years after naming Arthur as his heir, Richard departed the battleground that had become his temporary home, and set sail for England. The Third Crusade had been a brutal war of attrition, with vile atrocities committed by both sides, yet it had ended in a stalemate. Richard would now return to his true home, the heart of his empire, and he could begin to share with his young nephew some of the lessons vital to kingship. Except, he did not return. It would be another two years until Richard the Lionheart once more laid eyes on the nation over which he reigned.

Richard’s time in the holy land had not been without success. He had outclassed many of the other western leaders who had joined the Crusade, he led an army to a decisive, legendary victory against an opposing force twice size at the Battle of Arsuf, and he even besieged Acre whilst bedridden with arnaldia; a horrific illness that could cause immobilising fatigue, nightmarish fever, and the slow, painful loss of one’s hair and nails. He had been carried toward the city walls reclined atop a covered litter, mowing down his opponents with a crossbow. Yet for all these successes against his foes, he had also succeeded in galling a number of his former allies. Richard had irritated Philip of France with his refusal to share the prize of freshly-conquered Cyprus, and he had outright disgraced Leopold of Austria. When the city of Acre was won by a combined army of English, French, and Austrian troops, all three leaders had raised the standards above the city walls to flutter in what arid breeze graced the city. Richard was staggered. How dare Leopold, a mere duke, and a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire, raise his flag beside those of two great kings? Richard had his men rip the flag of Austria from the walls, and toss it in the moat. Enraged and humiliated, Leopold immediately gathered his troops and returned home, leaving Richard and Philip to continue their campaign. Philip of France withstood Richard only a little while longer, and soon also departed the holy land with his troops, leaving Richard to wage his holy war alone. Thus when Richard himself decided to return home, he was faced by a perilous journey through hostile territory, without any allies he could turn to.

Richard’s return had a less than ideal start. Shortly after setting sail, his ship landed in Corfu. At the time, the island was under the control of the Byzantine Emperor, who had been enraged by what he saw as Richard’s theft of Cyprus from under the Emperor’s nose. With his enemies closing in around him, Richard plotted a swift escape. Disguised in the armour of a Knight Templar, Richard fled the island with the company of only four of his most trusted attendants. It was not long until poor fortune found him once more. A storm found Richard’s ship as it crept round the coast, and he and his men were wrecked, washing up on the shore of Aquileia, a small city in the north east of Italy. Desperate, Richard and his men decided to embark on a perilous overland journey, heading north towards Saxony. The duchy was controlled by Richard’s brother in law, Henry the Lion, and the small band of men hoped this might prove to be a safe haven. They would never have the chance to find out. As they pressed onwards through the bitter cold, they were apprehended as they travelled north through the dense, snow-clad trees of Föhrenberge forest. A sortie of men at arms descended upon them, shackling them in irons and taking them captive. These soldiers seized their prey under the orders of a man who had fast become one of Richard’s most bitter rivals; Leopold the Virtuous, Duke of Austria.

Richard’s fortunes were turning from bad to worse. England was now a nation with an absent king — a captive king. He languished in his cell, whiling away the days composing poetry, feeling utterly betrayed and abandoned. All the while, the Angevin Empire was deteriorating. John, Richard’s famously nefarious brother, had been rallying rebel barons, dukes and knights under his banner, and was set on carving out his own slice of power whilst his brother remained absent, and his regents confused and disordered. Not only did he whip up foment unrest in England, but he also allied himself with the French king Philip II in an attempt to seize a number of Richard’s continental holdings. It wasn’t until 1194 that Richard was finally released. The warrior king squandered not a moment of his freedom. He immediately threw himself in to the fray, raising an army, and leading it against the irksome alliance of John and Philip.

No doubt young Arthur watched nervously as his uncle’s adventures unfolded. Arthur was still but a child of seven at the time Richard took up the sword against both John and the king of France, but regardless, had Richard been slayed in the holy land, had he perished in his cell, or if he was now to fall as he fought to retake his lands, kingship would pass directly to young Arthur. Given his age, if the young boy did receive the crown now, his early reign would be guided by a regent. Being first deprived of his father, and now living so long away from the guidance of his uncle, young Arthur might have come to realise that a prospect loomed for which he was not properly prepared; how could he hope to learn the lessons all young kings must, without the advice nor instruction of a leader more seasoned? It was not as if Arthur could look to his step-father, Ranulf de Blondeville, as a paragon for any kind of virtue, let alone as anything remotely approaching a strong leader — the man didn’t even control the duchy he ostensibly ruled over. However, in 1196, Ranulf would teach Arthur an unforgettable lesson. Arthur was about to learn first-hand just how fickle, deceitful, and cruel one’s allies could be. As Richard continued his battle against both his brother and the king of France, he summoned young Arthur and his mother, Constance, to his court at Normandy. Finally, it seemed the boy would have the opportunity to watch a king at work. Perhaps, if Arthur had made it to Normandy, he would have learned a great deal about the arts of war and siegecraft from his uncle, who at this point had earned something of a legendary status for his tactical expertise. But Arthur was not to reach Normandy. As he and Constance made their way from their seat at Nantes, towards Richard’s court in the city of Rouen, they themselves were seized. Constance and Arthur were unable to put up much resistance. Ranulf and his men captured them, and shipped them back to Brittany, where they would be kept under Ranulf’s watchful eye. When the news reached Richard the Lionheart, he was unsurprisingly enraged. Despite being midway through a war with both his own brother and the nation of France, he marched to Brittany, personally leading a force to free his nephew, the heir to the throne of the Angevin Empire. Here was an expedition that would prove unsuccessful for the famed warrior king. As he prepared to besiege Nantes, Arthur was whisked away. We are told he was taken by his tutor, along with his mother. It seems the tutor’s intention was to save him from the ensuing bloodshed, or to at least release him from the clutches of his nefarious step-father. Regardless, the choice of safe haven to which Arthur was whisked was a strange one. Whoever smuggled Arthur and his mother out from the walls of Nantes, and whatever their motivation may have been, they chose to take the young boy, the king of England’s nephew, and heir to the throne, directly to the court of Philip II, the king of France.

Despite Richard’s best efforts, his heir slipped from his grasp. Yet in Paris, Arthur found something he had been lacking thus far in life; a first-hand glimpse of a king at work. Not only that, but in the French king’s son, Louis, Arthur found something of a brother, too. The two boys were the same age, and in Paris they were raised together, learning the art of kingship side by side. He may not have realised it at the time, but Arthur’s new residence would have dramatic effects on his inheritance.

As the frigid winter of 1199 gave way to a spring of chilly showers, Arthur’s time was nigh. He was heir to the English throne, still spending his days at the Parisian court in the care of Philip II, a man at war with Arthur’s uncle, England’s current king. It was the start of March. The ground had thawed, the air had warmed, and across France, the armies of Richard and Philip were preparing to clash swords once more. Richard had seen a number of decisive victories, and was hungry for more. He had successfully convinced his turncoat brother to return to his side. John further proved his talent for underhanded treachery, exploiting the secrets and information he had gained from his erstwhile ally, Philip II of France, passing them on to his brother John to be used against the French king. It was Lent, a time in which all good Christians were beating their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks, committing to a renewal of their faith by not only curbing their consumption of meats and wines, but also their thirst for bloodshed. During these solemn forty days, Christians swore themselves off the battlefield, and dedicated their time to fasting, almsgiving, and sober prayer. Richard the Lionheart paid these traditions no such heed. Although he had recently signed a truce with king Philip of France, he was fighting his way through the province of Limousin. He had business crushing the revolt of Viscount Aimar V of Limoges, who had been persuaded to take up arms against Richard by none other than John, prior to his reconciliation with the Lionheart. If anyone had any remaining doubts as to John’s deceitful scheming, they were certainly dispelled as he bounced from side to side across allegiances, taking up arms alongside his brother, and waging war against the very people he had incited to join the war in the first place. With the knowledge of the French lands and plans that had been brought to him by his underhand brother, Richard likely felt unstoppable. The chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall tells us that Richard “devastated the Viscount’s land with fire and sword”, ploughing through the province of Limousin, set on besieging Château de Châlus-Chabrol, a humble castle in the tiny township of Châlus. As March began, Richard was amassing his troops outside the castle’s walls, preparing for, and expecting, a resounding victory. Neither he nor young Arthur could have known that before the next month would end, the crown of the king would pass to his heir.

The sun was setting on a frosty March evening, and Richard was feeling confident. He and his force had discovered that Château de Châlus-Chabrol was virtually undefended. No doubt, the castle would soon fall into his hands. Richard’s scouts had spotted only two knights patrolling the city’s walls. It was to be an easy final fight. One of these knights upon the wall was allegedly a boy named Pierre Basile. So ill-prepared for Richard’s siege was the castle, that Pierre had armoured himself with varying panels of plate in all manner of shapes and sizes, that he had gathered from around the castle. For a shield, he had liberated a large frying pan from the castle’s kitchen. Armed with his pan in one hand, and his crossbow in the other, he watched as the Lionheart’s assault force marched upon the castle. It’s said that when the English soldiers spied Pierre atop the battlements, clad in mismatched and ill-fitting armour, wielding a frying pan in front of him, they burst into laughter.

At heart, Richard was a warrior. He relished the thrill of battle. He was more a knight than a king. He saw no challenge in taking such a poorly defended tower from such ill-prepared foes. No troubadour would write a poem of such a one-sided, certain victory. So, lacking any insurmountable odds against which Richard could demonstrate his daring, he created them himself. He doffed his chainmail, leaving it with his men, and approached the wall alone. His self-assurance would prove fatal. He sauntered toward the castle, allegedly dancing out of the way of the bolts fired from Pierre’s crossbow. We are told Richard would leave each dive to the last moment, standing still whilst watching the bolts soar towards him, before spinning out the way only seconds before the bolt would hit him. He ducked and dodged bolt after bolt as he approached the wall. Pierre loaded another bolt into his crossbow. For him, this confrontation was personal. Richard had slain Pierre’s father, along with his two brothers, as the King laid waste to swathes of France in efforts to reclaim them. Pierre would have his revenge. He fired his final bolt. Richard watched as it flew towards him. As it drew near, he spun, skimming to the side. But the king had moved too late. The bolt had buried itself in his shoulder. Certainly Richard must have been in agony, but he knew well he could not show weakness before his men. Raising the call, he pushed on, signalling his troops to take the castle. In less than a month, he would be dead.

Richard lay in his tent, too weak to move. The castle had been seized, but it was to be a pyrrhic victory. The bolt had been removed, but the wound had turned gangrenous, the infection spreading across his arm and chest. When Château de Châlus-Chabrol had fallen, Richard ordered the man that had fired the fateful bolt to be brought to him. Shortly, Pierre Basile, the boy knight, stood before the king, expecting his punishment; a brutal execution. But the king gave no such command. As he lay dying, Richard issued a solemn, chivalric wish. So impressed was he by the boy’s ability, to have slain such a mighty king, he ordered Pierre be spared, and indeed even bestowed upon the young man a prize of one hundred shillings. “Live on,” he declared “and by my bounty behold the light of day.”

Richard had one last wish to decree before he passed, and this second wish would prove to be far more divisive than his reward to Pierre. The king’s final wish would send ripples throughout the Angevin Empire, sparking a bloody war that would be punctuated by brutal, cold blooded murder. As he lay in his bed, wheezing his last breaths, Richard summoned his closest advisors. He began his final decree with an admission; Richard feared that Arthur was too young to rule. Perhaps he was also concerned what effects such close proximity to the French crown may have had upon the impressionable young boy. How could he allow his mighty realm, an Empire that his father Henry II had forged with blood, sweat and tears, through years of toil and anguish, to pass to his nephew, a child he hardly knew? Perhaps he was also hoping that he would have had the opportunity to raise and guide the child before his final day. Alas, history’s plans had been different. Faced with this dilemma, Richard had a final change of heart. He had another heir in mind. This final command would spill countless pints of blood, and usher in what could be considered England’s darkest period of kingship. In his final days on earth, he declared that the crown was no longer to pass to Arthur of Brittany. Instead, upon the death of the Lionheart, rule of the Angevin Empire, and the kingship of England, would pass instead to the king’s brother; John.

Upon the king’s death, one of his most loyal retainers, an ageing knight just entering his fifties named William Marshal, paid a visit to another very important man, who like himself, had supported the now dead king’s realm, and guided his hand with his counsel. The man the old knight Marshal came to see was the Archbishop of Canterbury, Hubert Walter. Richard’s death had not yet been shared widely or publicly, and William Marshal rightly feared the prospect of succession. Richard had held the sprawling realm together, forged peace with France, and ushered in an era of glory for the crown. But he had done much of this through his impressive personality and wilful spirit, and without him, the future of the realm hung in a delicate balance.

Archbishop Walter had been expecting the visit. “Come now,” said archbishop Walter, as Marshal knocked upon his door. “Give me your news!” We are told that for some time, the pair mulled over their dilemma. In this foggy part of history, rules of succession were still hazy. Despite Richard’s wishes, either long past or quite recent, the dukes, barons, and common folk of the realm would still be divided upon who should inherit the crown; his brother John, or his nephew Arthur. Perhaps the pair even considered the possibility of keeping Richard’s dying wish to themselves, and quietly passing the crown to Arthur, as had been Richard’s decree years past. However, William Marshal was a knight unwaveringly loyal to the Plantagenet line. As far as he saw it, John was the next in line, thus he inherited the realm. To him, there was no choice in the matter. His former king had decreed it so, and thus it would be. Archbishop Walter was a man who felt himself more loyal to the realm itself than the wishes of any specific man. He knew John well, and feared what baleful effects the cruel man might invite into the realm as king. They argued for a long time. Marshal the knight of the Plantagenets doubted Arthur’s upbringing, and questioned the advice and guidance of those he had surrounded himself with. He argued that the boy did not like the subjects of his realm, and that he would no doubt cause them all “harm and damage”. Instead, he invited the archbishop to consider the claim of John, who Marshal argued was “nearest in line”. Archbishop Walter did not argue his case much further. The laws of succession could be twisted and weaved to one’s own wishes. Norman law supported the claim of the oldest surviving son of the former king that should be king (in this case, John, oldest surviving son of Henry II), whilst Angevin law favoured the oldest surviving son of Henry II’s oldest son; in this case, Arthur. It was easy to see how the matter could soon unravel into brutal open conflict, regardless of whatever Richard had decreed or wished. But the archbishop hadn’t the will to argue his case. Ultimately, he would stand by his ally’s decision. However, as the archbishop turned to depart, he left Marshal with one final warning against bestowing the crown upon John. “This much I can tell you,” warned the archbishop. “You will never come to regret anything, as much as what you’re doing now.”

The king was dead. The rush for the crown had begun. It mattered not what Marshal and Walter had decided, both John and Arthur saw their chance, and both hurried to seize it. It was John who first reached the throne, first taking control of the royal treasury in the castle of Chinon. He then set sail to England to have the crown bestowed upon him at Westminster Abbey, with the support of much of the English and Norman nobility, including the backing of William Marshal, and the reluctant and begrudging advocacy of archbishop Walter. The nobles of Brittany, Maine, and Anjou (the bulk of the Plantagenet Angevin Empire in France) were outraged. In their mind, it should be Arthur who deserved the throne. Not only did they cite Angevin laws of succession, but they also recalled the many crimes and treacheries of John, which were legion. The man had rebelled against his brother, the former king; he had invited an invasion of the Scots; spread the rumour his brother was dead whilst bribing the Holy Roman Emperor to keep the Lionheart in prison; and then, once Richard was finally freed, John had attempted to hand over Angevin holdings (such as Normandy itself) to Philip II, supporting him in a war against the English crown and begging the French king to support him on his own quest against his brother, before finally turning his coat again and stabbing his former ally in the back. How were they to hand over the crown to a man who had spent almost his entire adult life attempting to destabilise the very realm he now wished to lead?

The battle lines had been drawn. The nobility of Brittany, Anjou, and Maine raised their banners in support of Arthur, declaring him their king. Even Philip, John’s erstwhile ally, now supported young Arthur’s claim to the throne. Arthur led his force to Anjou and Maine, to ensure his control of the counties. With them in his grasp, the duchy of Normandy, which recognised John, was now surrounded on all sides; by Arthur to the south, and by Philip to the East. But whilst it may have seemed that John might not succeed in his plans by brute force alone, he was certainly capable of relying on his cunning to achieve underhand victories. After failing to take control of the city of Le Mans, a former stronghold of his father, narrowly escaping capture by Arthur and Philip’s armies, he hatched a plot.

William des Roches was a knight who had long served the Angevins. He had put down rebellions against king Henry II, fought alongside Richard in the Third Crusade’s many famous battles, and stood against the French king during the Lionheart’s struggle to maintain his French lands. When Richard died, des Roches threw his support behind Arthur. Arthur knew well he was fortunate to have such a venerable knight in his service, and thus chose the famed crusader to become his seneschal of Anjou, responsible for the defence of Le Mans, besides many other duties. William served the would-be king well, succeeding in capturing a strategically crucial fortress for Arthur, and even fighting to keep it from falling into the hands of the French king. But the winds of change were fickle. At the start of June, John launched a surprisingly effective military assault. His target was Maine, Arthur’s easternmost county, that lay just under Normandy. After a long summer of punishing conflict, the prospect of a wet autumn and a bleak winter loomed. When the weather turned, the opposing sides would be likely to reach a truce, waiting out the poor conditions until the weather would lend itself to fighting again. Thus, a decisive victory would serve John well. And it was a decisive victory he got. On September 13th, John repelled Philip’s forces from the fortress of Lavardin, which protected a vital artery for supplies into Le Mans. With their supply line compromised, Arthur’s supporters at Le Mans, including the noble knight des Roches, were forced to meet with their attackers, and come to terms. Here was John’s chance. Wisely, he appealed to des Roches’ loyalty to the Plantagenet/Angevin line, along with the knight’s long fostered opposition to the French crown. John convinced the knight that Arthur was little more than a puppet. The boy had been brought up in the court of France, surely, he insisted, des Roches could see that Arthur was firmly in the pocket of the king of France? If that weren’t convincing enough, John promised to reward des Roches well for his service; if he turned his coat for the greatest turncoat of them all, he would be rewarded with the seneschalship of Anjou. Whether the claims on Arthur’s loyalty were true or not, des Roches found himself swayed. He was now John’s man, and he would do as his new king wished. And what the new king wanted more than anything, was for Arthur, the “pretender to the throne”, to be brought before him.

When William des Roches met Arthur and his mother Constance just four days later, perhaps he greeted them as a friend. We don’t know whether he seized them by force, treachery, or both, but we do know that Arthur’s former ally swiftly had the boy firmly within his clutches. With nary a delay, William rushed the pair to Le Mans, a stronghold that had now slipped from their control. This time Arthur entered the castle not as its king, duke, or overlord, but as a prisoner. The young captive was brought before John. It seems Arthur knew the struggle had been lost. No doubt he feared the wrath of his uncle, so famed was he for his rage and his cruelty. We are told that the young man bowed his head and bent his knee. He was willing to make peace. It seemed the war for the crown was over.

Arthur and his mother were now captives in the grasp of the king of England. It seems that John may have even forgiven the slight of his nephew, as he certainly didn’t mete out any punishment immediately. Perhaps John saw no threat. Arthur had, after all, submitted to John, recognising his uncle as king, and with this, the young boy was now essentially “free”, although his kingly ambitions were certainly over. But something still irked Arthur and Constance. Whatever shaky amity existed between them and John, they did not trust it, and perhaps they were right not to. Within the walls of John’s stronghold, something was amiss. No doubt Arthur was cautiously anticipating some dreadful punishment; a dreadful punishment that had not yet come, but was certainly sure to. Fearful and distrustful, Arthur and Constance hatched their own plan. Mere days after Arthur’s submission to John, the pair fled, secreted from the walls by an ally veiled among John’s men. Through the night they raced, fleeing John, and retreating back to a familiar face. Arthur and Constance once more made their way to Philip’s court.

It might have seemed that this would have been another pivotal moment, yet another twist in the tale that could see Arthur crowned. But alas, that was not the case. Arthur and his mother were at this point not technically fugitives. Arthur had submitted to John, renounced his claim, and, ostensibly at least, made peace. Even so, having his nephew not only so far out of his reach, but also potentially under the influence of the French king would certainly have been quite the cause of concern for John. As far as John was concerned, despite Arthur’s outward surrender, the boy could potentially remain a dormant, simmering threat that could be convinced to take up the sword once more by the coaxing of one of John’s most potent nemeses; the French king, Philip II.

As the Seine meanders out of France to pour into the Channel, it winds through the commune of Vernon. As it does, it twists past a tiny, unremarkable hamlet named Le Goulet. It was here that John and Philip met in May 1200. The winter of 1999 had passed, and the world had ushered in a new century. If the meeting of the pair went favourably, it could well be the start of a peaceful and prosperous century for both England and France. They had agreed to meet at Le Goulet, an area to the far south of John’s duchy of Normandy, to sign a treaty that might bring an end to the hostilities between the two. But from the start, the treaty was far less than genial. Despite his support for Arthur, Philip must have been elated that John was now king of England. Richard the Lionheart was gone. Philip had been rid of the thorn in his side, and was now faced with an English king he hoped to walk all over. In Le Goulet, that is precisely what he did. The terms laid out for John were far less than favourable. Philip was willing to let John keep control of his continental possessions, but this concession would come at a price. John would need to recognise Philip as his suzerain — he kept his lands, but only through the good graces of Phillip. These were no longer lands John had earned, won, or inherited — they were gifts from the French crown, portions of land that John could look after, whilst paying Philip homage and tribute. Whilst the practical difference may seem minor, the change was a colossal insult to John, and an immense loss for the Angevin Empire. Furthermore, to keep control of Brittany, John was ordered to pay 20,000 marks, a colossal sum. However, in return, Philip would formally recognise John as King of England, and Richard’s rightful heir. If any doubts had remained before, surely now they had been dispelled. The message was clear. Arthur’s ambitions for the throne seemed well and truly dead.

This was certainly the impression that Arthur received. Arthur had viewed Philip as something of an ally; he had spent much of his childhood in the king’s court, raised alongside his son, Louis. Offended by what he saw as an unexpected betrayal, Arthur made the surprising decision to leave the court of Philip and return to John. It wouldn’t be long, however, until young Arthur once again became concerned as to his uncle’s intentions, and after only a short while by the king of England’s side, returned again to the king of France’s court. Arthur had clearly learnt something from his uncle; the art of fickly switching one’s alliances with the pace and unpredictability of changes in the wind. Here, once again in France, Arthur had another change of heart. It seemed that Philip did also. Just two years after the signing of the Treaty of Goulet, Arthur embarked upon a campaign against his uncle, in a mission to seize control of Normandy. He was joined by none other than Philip II. How far the decision was Arthur’s, and how far he may have been influenced by suggestions from the French king we shall not know. But the die had once again been cast. War between John and his nephew resumed. Arthur was not yet out of the fight.

The frost had melted and summer came again. The sun baked the pastures of Normandy. The Duchy was once more gripped by war. It was 1202, and the now fifteen-year-old Arhur was marching a force straight into the heartland of his uncle’s continental holdings. The people of Poitou, a county on the west coast, had risen up against John and now swore their swords to Arthur. Marching on Normandy backed by the might of the renegade county, with lords and knights loyal to the king of France harrying his enemy from the east, victory seemed certain for Arthur. As he pushed onward to John’s seat of power at Normandy’s northernmost tip, Arthur was tempted by a prize too good to refuse. Word had reached Arthur’s camp that John’s mother (also Arthur’s grandmother), was residing in the nearby Château de Mirebeau, virtually undefended whilst the majority of John’s forces were indisposed dealing with the French far north. The queen mother would certainly fetch an eye watering ransom, but more importantly, she’d be an invaluable bargaining chip. With his grandmother as his hostage, Arthur could force John to the table, and might even succeed in having him agree to stipulations as humiliating as those to which the English king agreed in Le Goulet. The soldiers marched, the sappers dug, and the siege engines rolled across the planes surrounding Château de Mirebeau.

Despite his many other shortcomings, John was not so dire of a strategist to realise just how untenable his position could become if he allowed his mother Eleanor to fall into Arthur’s custody. Thus, leaving a portion of his force north, at Château Gaillard to fend off Philip’s forces, John made a hasty march south. He had over three hundred kilometres to trek, and a journey that would take him through an entire duchy and two counties beside. With him he brought a beastly army of mercenaries, who were becoming nearly as famed for their cruelty as their master, along with William des Roches, who had once so ardently supported young Arthur. Miraculously, the mercenary army’s forced march brought them before the gates of Mirebeau on July 31st. It was an astounding feat. The unwieldy army had reached the castle faster than anyone could have expected or predicted, most certainly not Arthur, who had been caught totally unawares by his uncle’s troops, and found himself trapped between the defenders he had hoped to besiege, and the forces sent to relieve the siege. His luck had run out. The very next day, he was seized by John’s barons, and hauled back to Normandy, where he found himself trapped within a dank cell at Château de Falaise.

At Château de Falaise Arthur, and all of history, would learn what a brutally vicious man John was. The young boy was the grandson of a previous king, nephew to the current, and a duke in his own right. But to John, he was a threat; nothing but a pest, a wound that had been allowed to fester too long. By sheer fortune, however, he avoided what could have been a far more vile end than the one he eventually found. King John had connived a plan of sick genius. Arthur was a danger to him, but if by some misfortune the boy could no longer rule effectively, could no longer lead troops to battle, or perhaps, lost the ability to produce an heir, then he would no longer be such a threat. The chronicles tell us that John, seething, fearful, and desperate for revenge, ordered his Chief Justiciar, Hubert de Burgh, to visit the young duke in his cell. The king’s demands were vile. Hubert was instructed to remove the boy’s eyes, and castrate him. It was a horrendous decree, and would have been a torturous punishment for young Arthur. However, serendipity shone in the duke’s favour, and de Burgh could not bring himself to do it. Instead, in a strangely blundering move, he decided to return word to John and inform him that Arthur had died in his cell. This final, odd, paragraph of our story says a great deal more about the ineptitude of the court of the king that held Arthur captive than many other details could. When the news (the fallacious news), was leaked, the duchy of Brittany was up in arms, suspecting that their duke had been murdered. They were right to fear John’s intentions.

In 1203, the captive Arthur was dragged to Rouen, presumably closer to the court of John, and thus permanently under the king’s watchful eye. Obviously John had learned of de Burgh’s strange blunder, and had now decided to take matters into his own hands. The duke’s relocation also served the dual purpose of being an opportunity to have Arthur seen by the public, thus hopefully dispelling the rumours of his death, and quelling the simmering revolt in Brittany.

When Arthur reached Rouen, king John had him put under the charge of William de Braose. William had enjoyed a steady rise to fame and power under the Angevin kings. Not only had he become one of John’s favourite barons, but he also served both Richard and Henry II before him. He had earned a reputation as quite the seasoned soldier. He had fought alongside Richard the Lionheart when the former king had received his mortal wound, and during Henry II’s reign, he had perpetrated the Abergavenny Massacre, in which he lured a number of Welsh leaders (including three princes) with an invitation to a Christmas feast, ostensibly with the intention of making peace over the meal; with the men gathered in de Braose’s hall, he had the doors sealed, and the Welsh leaders brutally murdered. As if that wasn’t enough, de Braose then hunted down and killed one of the murdered Lord’s surviving heirs, a boy no more than seven years old. Since his arrival in John’s court, the king had showered de Braose with gifts, land, and titles; it would be safe to say de Braose was firmly in the king’s pocket, and likely would have done anything he commanded — unlike the boy’s prior captor, Hubert de Burgh. So in 1203, Arthur was a captive of the king’s court in Rouen, and under the watch of a particularly dangerous jailer. It was here that Arthur, the king that could have been, met his gruesome end.

It is the spring of 1203. War between John and Philip has resumed in earnest, and the scales are leaning firmly in France’s favour. Phillip’s forces were carving slices out of both Normandy and Aquitaine, threatening to leave John with but a slither of continental holdings. As the war turned sour for the English king, his rage simmered, and the famously unpredictable and erratic ruler became even moreso. It was around this time that young Arthur “disappeared”. Little more about his final days can be said with certainty, but several stories and explanations survive, detailed by various chronicles.

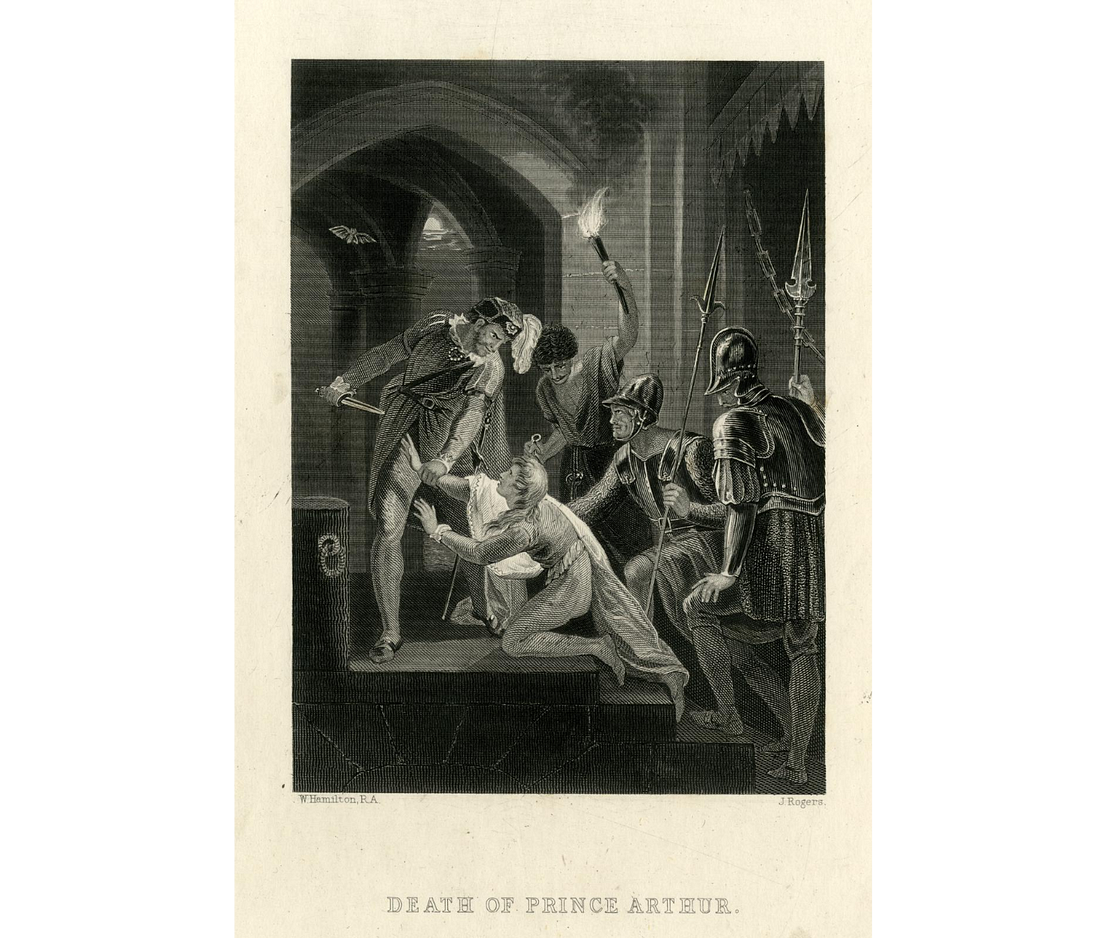

The Margam Annals record it like this. Easter was but a week away, and across Europe, the pious were abstaining from various luxuries. Yet much like his brother the Lionheart who had besieged Château de Châlus-Chabrol whilst others were supplicated in prayer, John also seemed less than inclined to keep the faith during Lent’s holy forty days. John had been enjoying a meal, and was deep in his cups. The king had a great many sorrows to drown. His war in France was going horrendously, he was being outclassed and embarrassed by Philip, and back across the Channel things were little better; he was disliked by his people and mistrusted by his barons. As the drink flowed throughout the night, the king dwelled further and further on his misfortunes, until his resentment bubbled up to the surface in an uncontrollable rage. The Annals say the devil himself seized John, and possessing him, drove him into an utter fury. John got up from the table, slinking away to seek out someone upon whom he could mete out his wrath. He crept down to the dungeons furious, and finding his nephew, slew him with his own hand. John dragged the boy’s corpse to the banks of the Seine, tied him to a stone, and tossed him into the river’s depths. Young Arthur’s body would later find its way into the net of a fisherman who, upon recognising the murdered duke, took him to the nearby priory. Cowed by their fear of the tyrannical John, the nuns buried the boy in secret, lowering him into an unmarked grave without even a mote of ceremony, fearing that anything otherwise may have attracted attention. Arthur was no older than sixteen.

Other chronicles tell the tale differently. Some contemporary sources noticed that after Arthur’s mysterious disappearance, his jailer, William de Braose, shot even further up the ranks of the English nobility, being showered with lands and titles, seemingly inexplicably. Were these his rewards from John, thanks for dirtying his hands with such a debased task? Many years later, when de Braose himself fell foul of the king, de Broase’s wife publicly claimed that she knew exactly what had become of Arthur, heavily implicating that the boy had been slain on order of the king. Perhaps unsurprisingly, and somewhat tragically fittingly, John had her seized, and locked in a dungeon with her son, where the pair were starved to death. Truly, John was a king from whom’s wrath none were safe.

However Arthur met his end, and at whose hand exactly, it is almost certain that he met his end by the will of John. Very shortly after the boy was last seen, John had sent a letter to his mother, including the cryptic message “God’s grace is even more with us now than I can tell you.” The king had rid himself of his irksome nephew, and he had reason to rejoice. Yet regardless, his luck would not turn. Rumours circled wildly regarding the end of the duke, and John’s fortunes in his war went from bad to worse. In the coming months, he would come before Philip many times in attempts to sue for peace. Here, young Arthur got his revenge. Each time John entreated the French king, he was met with the same response, the same impossible demand. “There shall be no peace,” said Philip, “until you first produce Arthur.”

Bibliography

Arnold-Baker, C., ‘Arthur of Brittany (1187–1203), in The Companion to British History (2 ed.) (London, 2001).

Cavendish, Richard, ‘Arthur of Brittany captured: August 1st, 1202. (Months Past)’. History Today, 52.8 (2002), p. 52.

Holt, J. C., ‘ King John and Arthur of Brittany’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, 44 (2000), pp. 82–104 .

Jones, Dan, The Plantagenets: the Kings and Queens Who Made England (London, 2012).

Malý, Jan, ‘Two Treaties of Messina 1190–1191: Crusading Diplomacy of Richard I’, Prague Papers on the History of International Relations, 1 (2017), pp. 23–37.

Morton, Richard E., ‘Arthur of Brittany (1187–c. 1203), in The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages (Oxford, 2010).

Leave a comment