This essay was originally published on Medium on February 21st 2024.

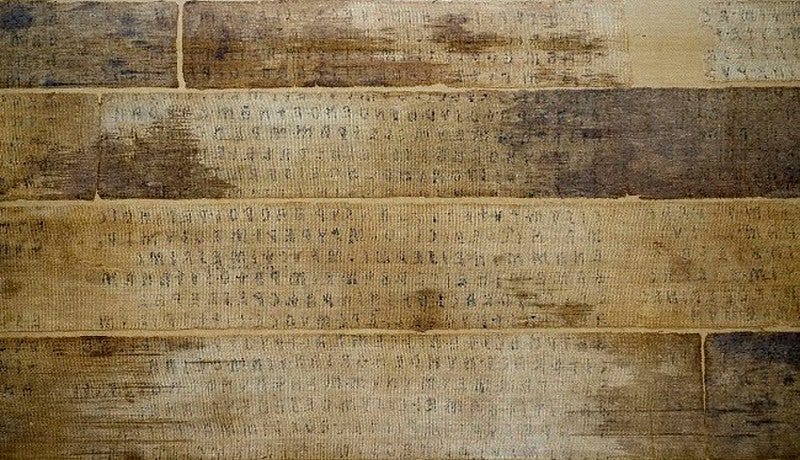

How did an Egyptian mummy end up in Croatia, and what secrets are held within the lost language written upon her bandages?

Some time around 1848, a man named Mihajlo Barić found himself in the Egyptian city of Alexandria. Few records on the details of Barić’s life remain. By the time he died in 1859, no one could have guessed the accidental contribution he had already unwittingly made to history. What we do know, is that during a visit to Egypt, Barić purchased a rather unusual souvenir: a sealed sarcophagus. Upon returning to his home in Vienna, Barić opened the sarcophagus to reveal the unidentified mummified woman within, alongside tattered scraps of ancient Egyptian papyrus. At some point, Mihajlo removed the bandages that clad the mummy, perhaps to better allow friends and guests to marvel at the ancient, dessicated corpse underneath, which he allegedly kept propped up for display in his home.

When Barić passed away, it was his brother who took charge of the mummy, along with her bandages, later giving both to the National Museum in Zagreb. Whether either of the Barić brothers had noticed the inscriptions on the bandages or not we can’t know, but if they did, they were certainly unaware of just how important they would become. The museum’s curator of archaeology, Mijat Sabljar, was likewise unaware. When the artefacts arrived at the museum, Sabljar recorded the bandages as being “inscribed with Egyptian letters”.

He was wrong.

For the next thirty years this mistake would go unchallenged, the museum and its staff blind to the true value of the object held within their collection. No doubt when the museum first accepted the donation from Barić, they had little inkling that it would not be the mummy that proved to be one of the most mysterious relics they held, but the bandages she had once been wrapped in.

To better understand the importance of the woman who would come to be known as the Zagreb Mummy, let’s first go back even further, to briefly trace the history of another artefact.

The year is 196 BCE

Ptolemy V is officially crowned king of Egypt. He is the fifth member of the Ptolemaic royal house, a dynasty that has ruled over Egypt since 305 BCE. They will prove the longest, and last, dynasty of ancient Egypt, ending eventually with the suicide of perhaps the most famous of the Ptolemaic line, Cleopatra.

To mark the occasion of Ptolemy V’s coronation, a gathering of priests have drafted the ‘Memphis Decree’, a proclamation celebrating and commemorating the young king. To ensure that as many of Ptolemy’s subjects as possible see this decree, it has been engraved upon a number of great stone tablets, each of which are to be placed within the many temples scattered across the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt. But it is not enough that the citizens of the kingdom see the decree, they must be able to read it. To ensure it is read by the greatest number of literate citizens, the message has been engraved in three different scripts:

- An ancient, sacred script reserved for religious inscription

- The common written language of the Egyptians of the time

- And finally, the native language of king Ptolemy, his family, and his royal court

Sixteen years later Ptolemy would be dead. And what would become of the stones that bore the Memphis Decree?

Perhaps lost, perhaps destroyed, most likely forgotten.

The year is 1799 CE

Nearly two millennia have passed since Ptolemy’s coronation.

Napoleon Bonaparte has sailed his fleet to Egypt, and is busy establishing control over the cities of Alexandria and Cairo. He is preparing to defend his newly conquered land against both the Ottoman and British Empires, along with a number of local uprisings.

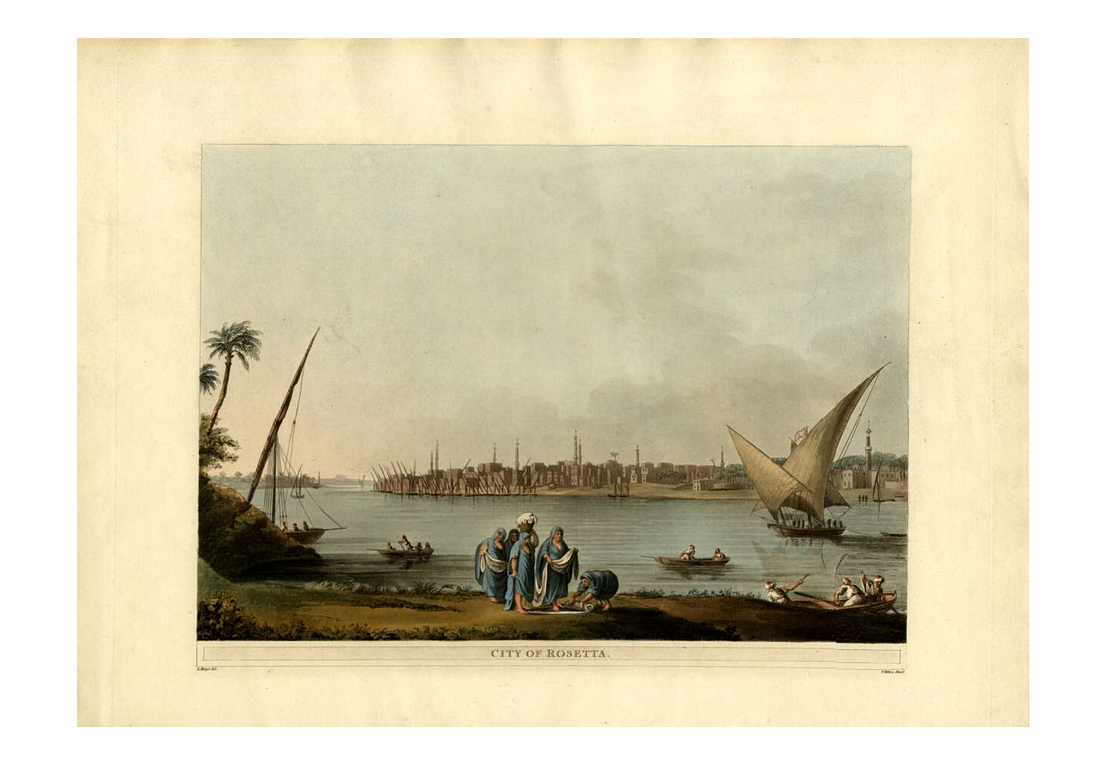

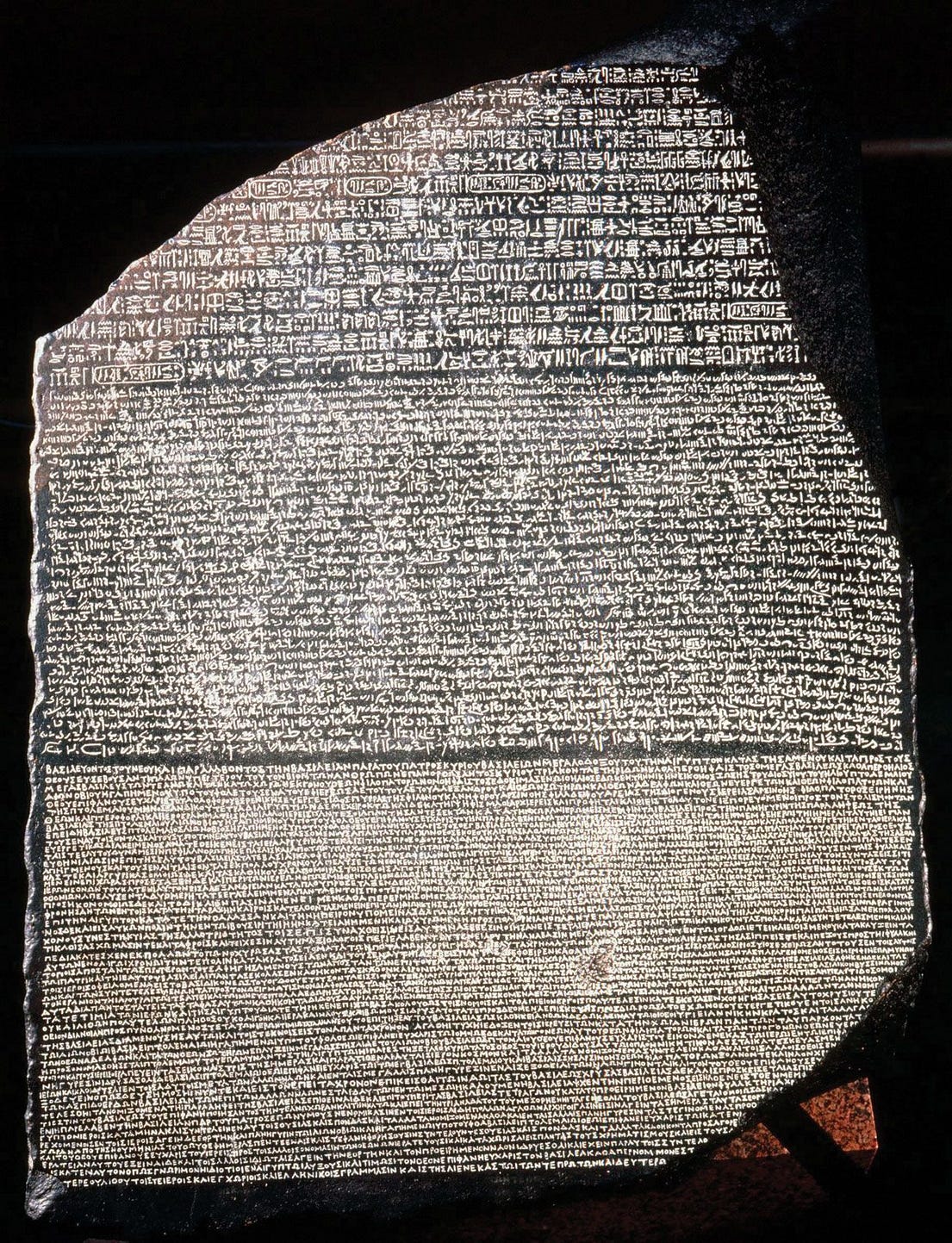

It is said Napoleon’s soldiers are digging near their fort in the town of Rashid, when they come across a colossal slab of black rock buried in the sands. They haul it from the ground, and find it to be covered in ancient inscriptions. Upon close inspection, they notice the inscriptions have been carved in what appear quite clearly to be three different languages. It is an engineer named Michel Lancret that reports to the expedition’s Egyptology association, the Institut d’Égypte, that the stone’s first inscription appears to be in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, and the third has been written in ancient Greek. He hypothesises, rightly, that the stone bears a multilingual inscription; an identical message repeated in three different languages.

Nearly two millennia have passed since Ptolemy’s coronation, and these soldiers had just unearthed one of the great slabs that recorded the now long dead king’s decree. The discovery is named after the town in which it was discovered; Rashid. Or as the French called it, Rosetta.

The Rosetta Stone would go on to become one of the most important discoveries in the history of Egyptology, and would prove instrumental in the decipherment of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. At the time of the Stone’s rediscovery by Napoleon’s troops, there was much speculation about how Egyptian hieroglyphics might be read, but little consensus. Hieroglyphs were still a code waiting to be cracked.

It soon became clear that the Rosetta Stone had been inscribed in the following scripts and languages;

- Egyptian hieroglyphs — the sacred script reserved for religious inscription

- Demotic — the common written language of the Egyptians of the time

- And finally, ancient Greek — the native language of king Ptolemy, his family, and his royal court

Whilst hieroglyphs and Demotic had up until then proved a great enigma for historians, linguists and epigraphers, Ancient Greek was a puzzle already solved. Scholars had been translating the works of Homer, Herodotus, Sappho and Plato for years. All these historians needed to do was translate the Greek inscription, and then they would know what the hieroglyphs said. By using other clues like sentence construction and the placement of the names of people and places, the mysteries of the hieroglyphs began to unravel. But the path ahead was still hazy. Which of the Egyptian glyphs correlated to which of the Greek words?

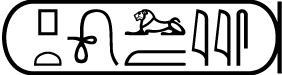

Prior to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, it had long been argued that hieroglyphs were purely logographic, meaning that each symbol represented an idea, normally one related to the symbol’s appearance. In such a system, it might be assumed that the sign below has something to do with a lasso, a lion and two reeds. An inscription about catching lions in the reeds, perhaps?

Through a combined effort by a number of historians, a series of new discoveries were made, many aided by the newly rediscovered Rosetta Stone. Firstly, they hypothesised that symbols within cartouches (the small, oval shape that encloses the hieroglyphs above) were names. Secondly, they reasoned that hieroglyphs could be used phonetically (each symbol representing a sound) when writing foreign names — Greek names, such as ‘Ptolemy’, for instance. On these principles, Egyptologist Thomas Young suggested that the symbols within the above cartouche had the following phonetic values:

𓊪 — p

𓏏 — t

𓍯 —

𓃭 — ‘lo’ or ‘ole’

𓐝 — ‘ma’ or ‘m’

𓇌 — i

𓋴 — ‘osh’ or ‘os’

Therefore, the symbols can be read as: ‘ptlomaios’, the Greek form of Ptolemy.

Today, it’s understood that the symbols actually represent the following:

𓊪 — p

𓏏 — t

𓍯 — o

𓃭 — l

𓐝 — m

𓇌 — ‘i’ or ‘y’

𓋴 — s

Still, Young was remarkably close. But full decipherment was not yet in reach. Since Young had argued that it was only foreign names that were written phonetically, his discovery could only be used to decode a miniscule fraction of the Rosetta Stone, and by extension, any other Egyptian hieroglyphic writing. Imagine finding a Russian copy of Crime and Punishment and only being able to translate non-Russian names. You’d never have a chance at understanding the book. (Unless of course you are Russian, in which case, this makes for a pretty terrible comparison). This was the new challenge faced by Egyptologists. It didn’t matter that they could now read the names “Ptolemy” or “Cleopatra” on obelisks, tombs and papyri — every single other inscription remained totally unintelligible.

It was French Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion that ultimately made the leap that would lead to revealing the secrets held by the hieroglyphs. First, he suggested that perhaps hieroglyphs could be used phonetically to write any names, not just non-Egyptian ones. From there, he made another bold conjecture: what if it wasn’t just names?

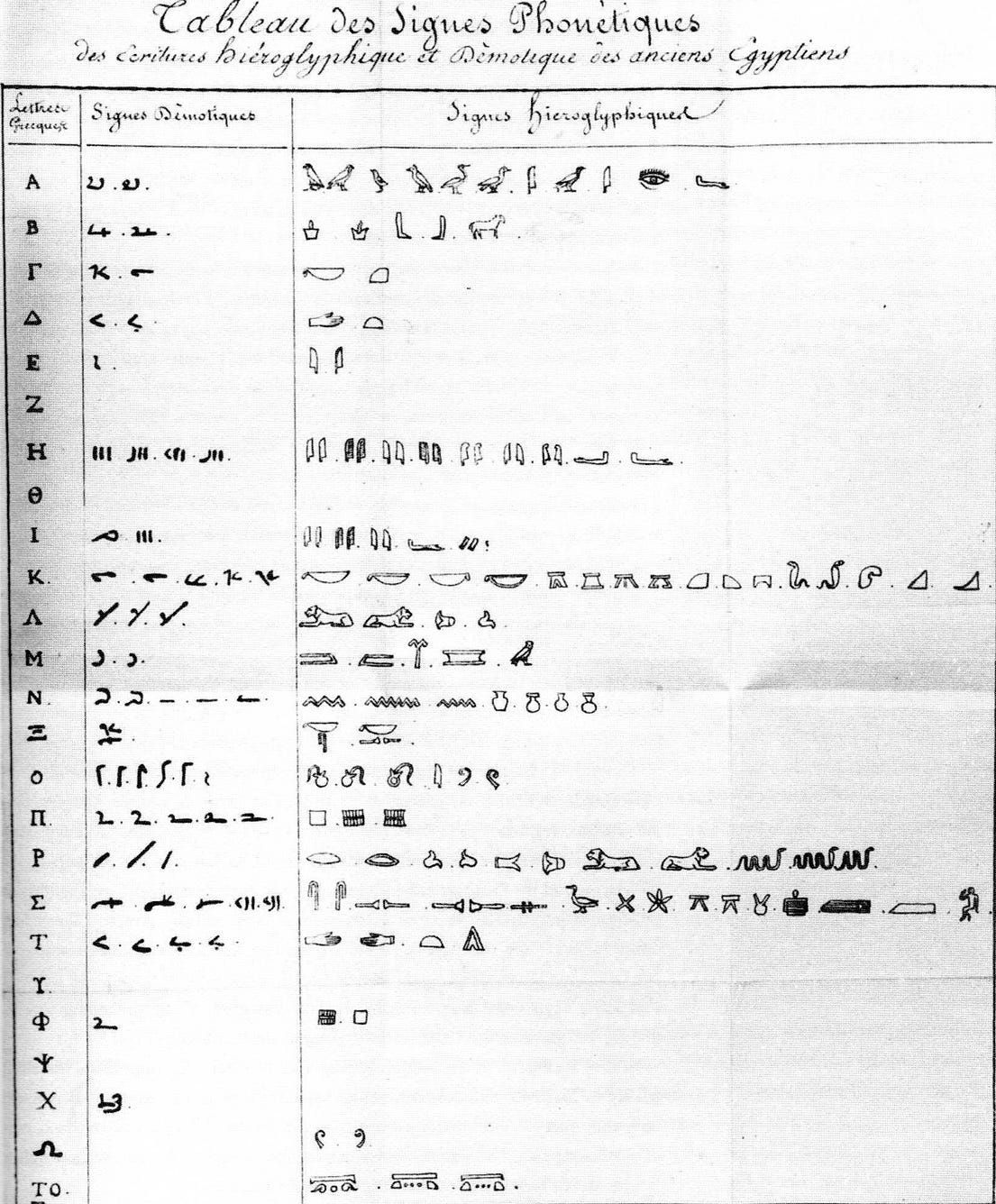

Eventually, Champollion would go on to produce a table detailing the phonetic values of many of the Egyptian hieroglyphs and Demotic letters present on the Rosetta Stone. Thanks to his foundation, and the work of those before him, we now know today that Egyptian hieroglyphs possessed logographic and syllabic qualities, meaning they could be used to represent entire words and ideas, as had originally been believed, but they could also be used to represent sounds. For example, the ‘vulture’ symbol — 𓅐 — can be used to mean, unsurprisingly, ‘vulture’ but can also be read as the sound ‘mwt’.

In the modern day, scarcely an Egyptian hieroglyphic inscription remains that is totally out of reach to a translator. An entire civilisation, buried nearly four millennia in the past, can now speak to us through the inscriptions that cover their belongings, scrolls, stones and tombs — and we can understand.

The Rosetta Stone is an example, probably the most famous example, of how the discovery of some inscribed artefact has allowed historians to decipher languages long thought lost and inaccessible. The Rosetta Stone was a particularly valuable find thanks to the fact that it was a multilingual inscription; the unknown languages of Egyptian hieroglyphs and Demotic could be compared to the known Greek inscription, vastly aiding in decipherment. Multilingual inscriptions are something of a holy grail for any scholars attempting to “crack” the codes of ancient languages. What presents a far harder challenge is a monolingual inscription — a piece of writing that is only recorded in the lost language under study.

This, for a long time, has been the painful challenge faced by those trying to study the Etruscan language. The Etruscans lived nearly three thousand years ago, inhabiting northern Italy from around 900 BCE, up until being swallowed by the ever expanding empire of their neighbours, the Romans, in 27 BCE. The Etruscans remain an intriguing ancient civilisation who left behind a range of fascinating artefacts, but most beguiling, a language we cannot understand.

However, Etruscan writing is not entirely unintelligible. Historians can tell from the appearance of the Etruscan alphabet that it was likely based on that of the Greeks (a claim strengthened by the regular contact between the two civilisations) and it’s also argued that it later likely influenced the Latin alphabet (the alphabet you’re reading right now). Finally, linguists are able to assign phonetic values to Etruscan, meaning they know what sounds the letters make — yet whilst this allows historians to read Etruscan words aloud, they are far less certain of the meanings of these words. For example, for a long time linguists knew that the Etruscan word “𐌂𐌉” was pronounced “/ki/” (a little like the English word “key”), but they didn’t actually know what the word meant up until around the 1960s. As of now, less than one hundred Etruscan words can be translated with much certainty. Their secrets remain mostly locked in the past.

For those interested in Etruscan, an “Eturia Stone” that bore some lengthy Etruscan inscription alongside a message in a well known script (say for example, Latin) could potentially explode the corpus wide open, allowing for all the previously discovered Etruscan inscriptions to be re-examined, their secrets perhaps revealed. Unfortunately, such a relic does not exist — or if it does, it is yet to be discovered. Some bilingual inscriptions in Latin and Etruscan have been discovered, and they have provided new and illuminating information on the language, but these inscriptions are mostly incredibly short. The shorter an inscription, the less it can reveal. Perhaps the closest discovery we have to a Rosetta Stone of Etruscan is that of the Pyrgi Tablets. These gold plaques, rediscovered in 1964, bear what appear to be matching (or at least incredibly similar) inscriptions, two in Etruscan, one in Phoenician. These are still rather short, nowhere near in length to that on the Rosetta Stone. Yet fortunately, since Phoenician is an ancient language that can be mostly read and understood, historians have been able to use the Phoenician writing to make tentative translations of the Etruscan inscription. It was the discovery of the Pyrgi Tablets and the comparison of the Etruscan text to the Phoenician that finally revealed that the Etruscan word ‘𐌂𐌉’ meant ‘three’.

All of this is to say, that whilst much of the Etruscan language, and therefore Etruscan culture, still remains obscure, steady efforts are being made at slowly piecing together the clues to provide a clearer picture of this long-forgotten language.

Unfortunately, all of the Etruscan inscriptions that have survived the test of time are on inorganic materials like tablets, gravestones or mirrors, and all of these inscriptions are by their nature, generally rather short. Longer Etruscan texts, if they ever did exist, were likely written on organic materials (like paper or fabric), and unfortunately, these materials rarely survive in the archaeological record thanks to their habit of either rotting or crumbling into dust.

If only one of these longer Etruscan texts had survived somehow, it could provide a vital key to better understanding this ancient language. But no such Etruscan book has ever been found. At least, not in Etruria…

It is 1868, and the National Museum of Zagreb receives an influx of new Egyptian artefacts, and their collection grows considerably. In an attempt to organise, categorise and curate their ballooning collection, the museum calls upon Heinrich Brugsch, a prominent Egyptologist from Germany. During his time with the collection, he inevitably comes across the bandages that once wrapped Barić’s ‘Zagreb Mummy’, and when he does, he notices something that the museum had yet to realise.

The writing on the bandages isn’t Egyptian.

At least, Brugsch doesn’t think it is — he has no idea what language it might be. Over twenty years later, Brugsch shares this peculiar discovery with a colleague, Jakob Krall. Krall is intrigued. The museum agrees to send the bandages to Vienna so Krall can have a look at them. A year later, in 1892, Krall publishes his findings in a book. Brugsch was right: the inscription on the bandages isn’t Egyptian.

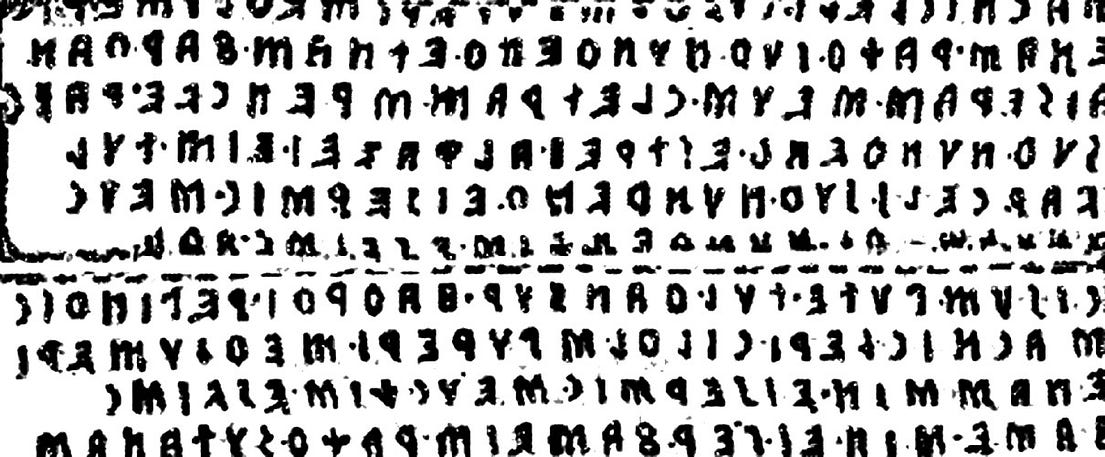

It’s Etruscan. It’s the longest Etruscan inscription ever discovered.

Why would a mummy be wrapped in bandages bearing the words of a civilisation separated from Egypt by 2000 kilometres of sea?

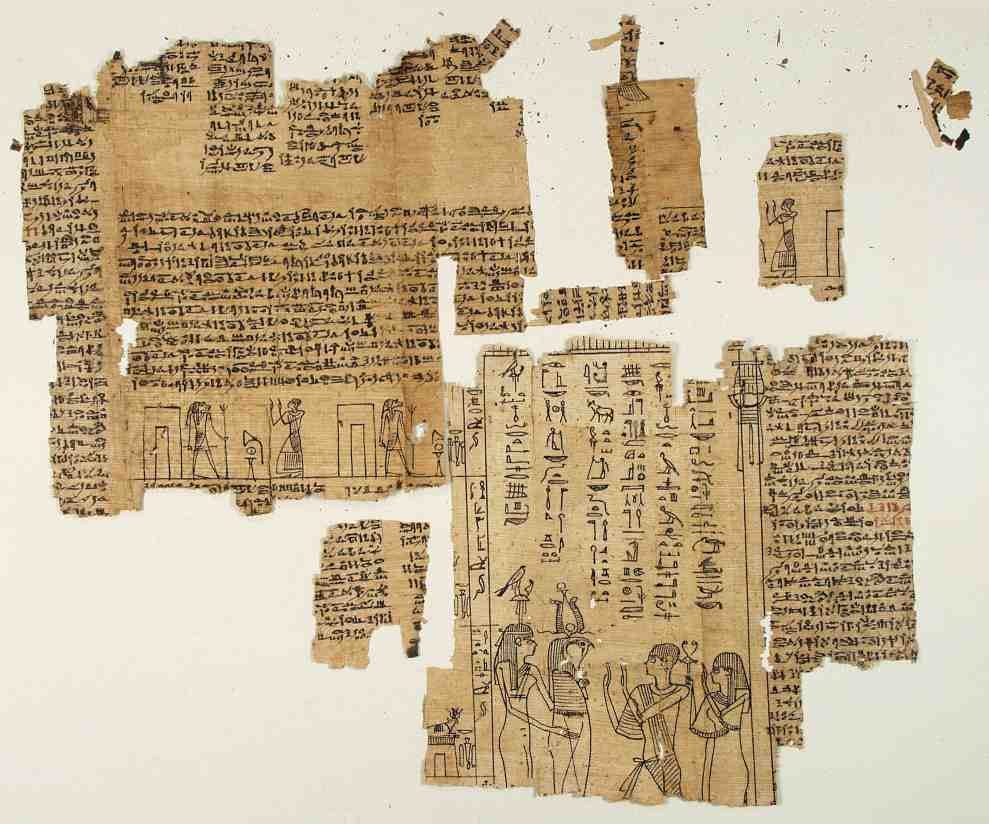

Perhaps if we could read the inscription clearly, it might provide a clue. Examination of the bandages, which historians have named the Liber Linteus Zagrebiensis, has revealed that they were likely a linen book (which is exactly what liber linteus means) that seems to have been cut up and repurposed as bandages. The fact that columns and strips of the book appear to be missing provide support to this idea. If this is true, it’s very well the oldest surviving European ‘book’ in the world.

The existence of the Linteus might suggest that writing on linen books was common among Etruscans, but as we know, since organic materials like linen degrade so easily, it’s almost impossible that they survive the test of time to be discovered in the modern day. Hence why almost all the Etruscan inscriptions that historians have access to today have been discovered inscribed on materials that far better weather the sands of time, such as bronze, stone or clay. The Liber Linteus, however, by peculiar coincidence, achieved the impossible. Thanks to the mummification techniques performed on the Zagreb Mummy, the Liber Linteus, in which the body was wrapped, has been preserved almost as well as the mummy itself. It’s by the fortune of this strange mystery that we now have such a rare surviving example of Etruscan writing. Finally, historians have their hands on an Etruscan book, something that should have been impossible.

Some impressive translation work has revealed a great deal about the words written upon the Liber Linteus, but this work has unfortunately been limited by our restricted understanding of Etruscan. What is clear, however, is that the names of a number of gods worshipped by the Etruscans have been written on the Linteus, alongside a series of dates. This has lead some historians to suggest that the Linteus could be a kind of calendar, possibly a religious calendar. A tentative translation of the text by L. B. van der Meer seems to suggest it might make reference to rituals performed at funerals. Could this by why the book was wrapped around a corpse?

In his 2006 article on the subject, Croatian Egyptologist Igor Uranić examined a range of evidence that could help to uncover the identity of this Egyptian woman wrapped in an Etruscan book. Analyses such as x-rays and carbon dating have revealed a lot about the Zagreb Mummy. She was no older than 40 when she died. She was buried with a cat. She was mummified around 390 BCE. As Uranić points out, the evidence seems to suggest that the woman died some time either in the Late or Ptolemaic period (but certainly long before Ptolemy V’s day, if you were wondering) — periods in which “numerous foreign colonies existed in Egypt.” Could it be the case then that the Zagreb mummy was simply an Etruscan woman who had died in Egypt, her burial an amalgamation of the practices of her motherland and the land she now called home?

For a while, it was believed another clue might lie within the tattered scraps of ancient Egyptian papyrus that Barić had found lying beside the mummy when he had first opened that sarcophagus. For a while, it was believed these tattered remnants might hold another clue. These papyrus scraps turned out to be fragments of a Book of the Dead, a funerary text that was often placed alongside the dead within their coffins in ancient Egypt. In Egyptian tradition, the name of the deceased would be written multiple times throughout their copy of the Book of the Dead, thus when these books are rediscovered within a tomb or alongside a body, they can prove useful aids in identifying exactly who it is they have been buried alongside. This specific Book of the Dead was dedicated to a couple; Perekh-Hensu and Nesi-Hensu (in Uranić’s 2006 article he writes their last name as Khons, but uses Hensu in his later work). In which case, surely the mummified Egyptian wrapped in Etruscan is Nesi-Hensu, given that this is the name written in the Book of the Dead alongside which she was buried?

If you do a bit of research online, you’ll find that the majority of sources (including the National Geographic) suggest that the Zagreb Mummy is indeed Nesi-Hesnu, but do some further digging and you’ll find this actually seems quite unlikely. In later research, Uranić revealed that the Book of the Dead found in the sarcophagus alongside the Zagreb Mummy is one hundred years younger than the mummy herself. She can’t be Nesi-Hesnu, and the papyrus scraps of the Book of the Dead that had been found within her coffin never belonged to her at all. However she came to be “in possession” of this Book of the Dead remains a mystery. It certainly couldn’t have been placed in the sarcophagus when she died, given she was mummified a century before the papyrus had been written. It seems likely that whoever sold Barić the mummy in 1848 might have included scraps of papyrus taken from a different sarcophagus.

All this evidence seems to point toward two possibilities.

First, the woman in the sarcophagus, whoever she was, was an Etruscan living in Alexandria. It isn’t impossible. It was a diverse city, drawing in people from all corners of the Mediterranean. Many of these settlers were soldiers, but the historical record also provides evidence of foreign weavers, dancers and singers who had been settled in Egypt at around the time that this puzzling woman passed away. However, as Uranić pointed out, there’s no record of any Etruscan colony in Alexandria, or in any part of ancient Egypt, ever. Yet, that doesn’t mean one didn’t exist, nor was a colony required for this woman to settle in Egypt from Etruria, and bring a part of her culture along with her.

This question leads us to the second possibility. Perhaps the Zagreb Mummy is a strange and somewhat sad reminder of a civilisation falling from its apex. The woman was mummified long after the golden age of Ancient Egypt, during a period in which rival Pharaohs fought to maintain control over a volatile throne. Uranić has suggested that in these “impoverished and crisis-stricken” times, it wasn’t uncommon for funerary gifts to be reused. These could include, for example, sarcophagi, the Books of the Dead, or even bandages. Certainly it seems, given the way the Liber Linteus had been sliced up, that if it had any significance to the deceased, the embalmer paid little heed to whatever importance the Etruscan inscription may have once held. Might it be the case that the she was buried in bandages taken from a repurposed book from a land she didn’t know, written in a language she couldn’t read?

It’s easy to forget, amidst all this mystery, that this woman was not always “the Zagreb Mummy”, but a person like you or I, with a name and with a life, not some inanimate artefact to be puzzled over like the Rosetta Stone. The topic of how historians, archaeologists and all people in general treat the relics of the past that also happen to be humans is one that’s unfortunately beyond the scope of this article, but it’s worth remembering that what Barić purchased, way back in 1848, was the body of a person, a real person, even if long dead. When we bear this in mind, and approach the Zagreb Mummy with not only pure scientific analysis but also compassion and understanding, the two possibilities become all the more moving. Was this an Etruscan woman who had for some reason sailed to a distant kingdom she didn’t know, a kingdom in which she was unlikely to ever see someone else from her homeland? If so, why make the journey? If not, was this a noble Egyptian, her family struggling in a time of economic strife, forced to bury their loved one wrapped in scraps of some strange book that had somehow crossed the Mediterranean to reach them?

We are unlikely to ever find another linen Etruscan book as well preserved as the Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis, but we can still hope for other Etruscan relics to be unearthed that will allow for the language’s continued decipherment. Whatever other secrets the Liber Linteus contains will remain secret until the lost language of Etruscan has been better reconstructed, and texts in this ancient script can be translated with some more certainty. Yet even then, it seems the origin of the woman we now refer to as the Zagreb Mummy might still remain a mystery lost to time.

𐌀 𐌁 𐌂 𐌃 𐌄 𐌅 𐌆 𐌇 𐌈 𐌉 𐌊 𐌋 𐌌 𐌍 𐌎 𐌏 𐌐 𐌑 𐌒 𐌓 𐌔 𐌕 𐌖 𐌗 𐌘 𐌙 𐌚 𐌛 𐌜 𐌝 𐌞 𐌟 𐌠 𐌡 𐌢 𐌣

Bibliography

- van der Meer, Lammert Bouke, Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis / The Linen Book of Zagreb: A Comment on the Longest Etruscan Text (Leuven, 2007)

- Parkinson, Richard, Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone and Decipherment (Cambridge, 1999)

- Robinson, Andrew, Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World’s Undeciphered Scripts (London, 2009)

- Uranić, Igor, Contributions to the Provenance of the Zagreb Mummy (2006) — Accessible online here

- Uranić, Igor, Liber Linteus i Zagrebačka mumija (2019) — Accessible online here

Leave a comment